The Annotated Nightstand: What Brandi Wells is Reading Now and Next

Featuring George Eliot, Jeanette Winterson, Julie Otsuka, and More

Brandi Wells’ unnamed protagonist sweeps, mops, wipes down, and disinfects an office while its daytime workers sleep. “I know them all,” The Cleaner tells us. “I’ve seen the grossest things about them, their half-eaten and molding snacks, their vaguely sexual doodles.” Wells gives us the depressing realities of The Cleaner’s invisible labor, beginning with shit smears on toilet seats to abandoned sandwiches in desk drawers. In its starred review, Publishers Weekly states, “Rarely has cubicle culture been depicted in such griminess or with such glee.”

Because of the nature of her work and her schedule, The Cleaner is only apparent if she fails to clean something well—and, as fastidious as she is, she never fails. At one point she describes how she takes her time between window scrubbings so the new clarity will be a “shock.” “Once everyone notices how clean it is, they’ll realize I exist,” she tells us. “They’ll be so embarrassed they hadn’t thought of me before.”

Throughout her shift, The Cleaner digs through employees’ desks to figure out who they are (Mr. Buff uses protein powder, Yarn Guy is a knitter), and to determine who deserves help—or punishment. At one point, The Cleaner throws away a self-help book in the desk of The Intern. By its description, the book sounds awful (“a man on the cover, pointing accusingly at the reader”). So, at first, one might think, “Good! Expel whatever misogynist crap that might lie between those covers!” That is, until The Cleaner explains her reasoning: if she leaves the book, more people will start to read and heed self-help texts, take dubious supplements, go full woo-woo, and “That kind of atmosphere isn’t conducive to productivity.” She doesn’t exploit her proximity to these people through their stuff—and emails and search histories—for fun or to stick a thumb in the eye of capitalist hacks.

Instead, The Cleaner’s efforts are to keep the place humming like a well-oiled machine. Her mind, access, and inconspicuousness are her sharpest tools. “It’s not a crime to care about other people,” The Cleaner tells her one coworker, a security guard named L. L., slapdash in her approach to her job, isn’t convinced. “‘It very nearly is,’ she says. ‘The way you do it.’”

What might feel like a monotonous story about a monotonous job—a person comes and cleans, has one coworker, briefly talks to the delivery person—Wells manages to give us a page-turner plot with biting, grander implications. Here we have a person who has arguably gone whole hog on the enterprise of her career and its capitalistic value. When one’s job is their sole purpose—arguably one of America’s loudest directives—the potential threats toward life’s meaning are rampant.

When The Cleaner realizes the CEO of the company is engaging in nefarious acts that risk the health of the company, the stakes are undeniably higher for her than anyone else. While she does much to control her environment, fantasizing about the narratives she shapes through her exploits, the reality is that The Cleaner remains invisible to those she feels she knows best. The dark commentary Wells builds regarding capitalism and work is undeniable.

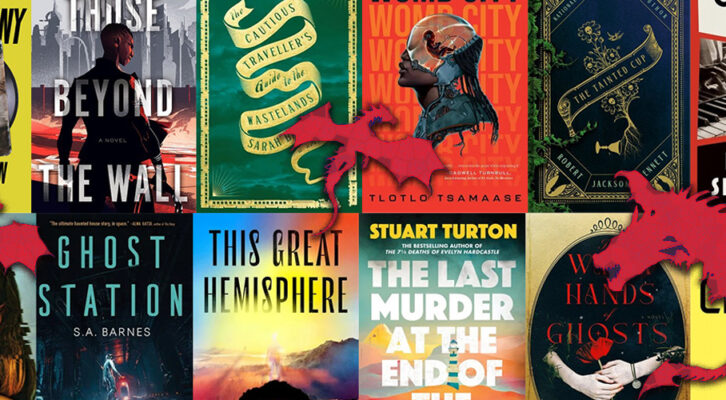

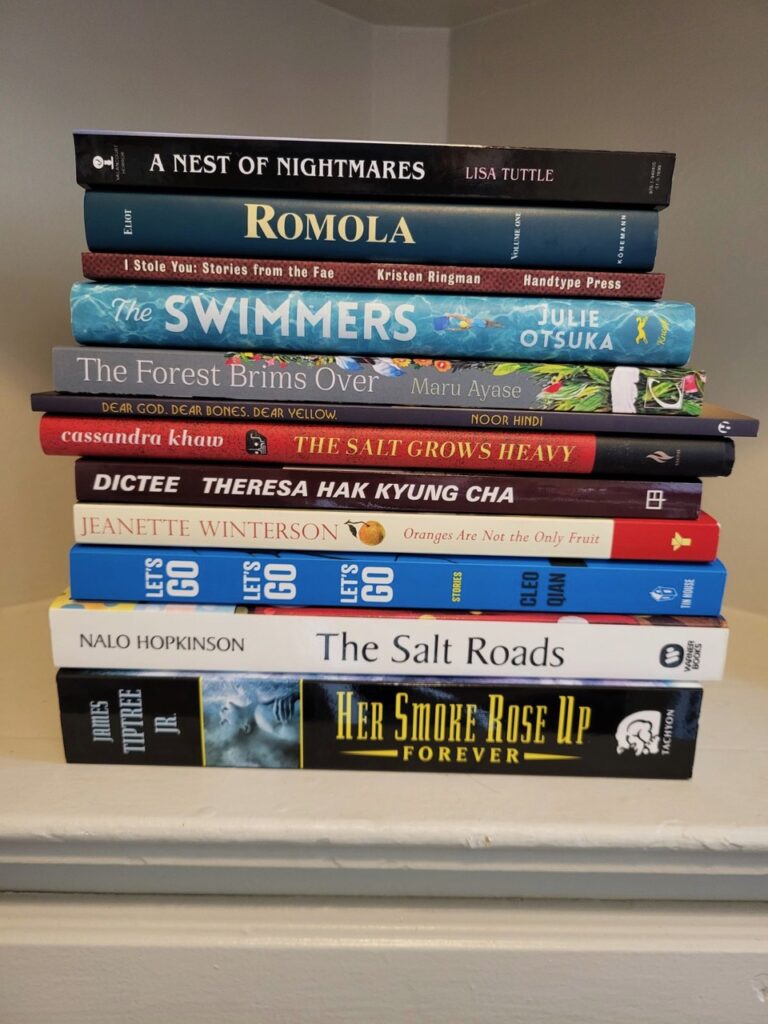

Wells tells us of their to-read pile, “Because of migraines, I do so much of my reading via audiobooks. I considered sending you a photo of those—most of them are new releases. But I still can’t help myself in a bookstore, love to carefully pick through their catalogue, and also peruse their staff picks. I love seeing what booksellers recommend.”

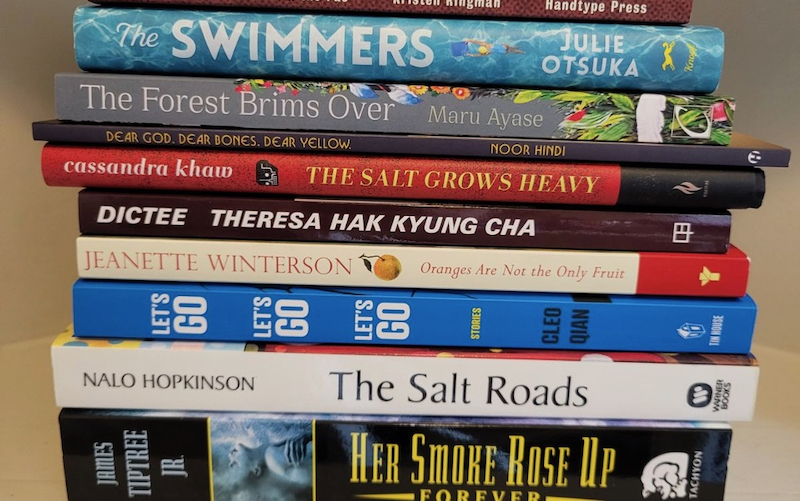

Lisa Tuttle, A Nest of Nightmares

This is the first short story collection by the fantasy and horror writer Lisa Tuttle. Tuttle famously refused the Nebula Award for Best Short Story in 1982 because another author had disseminated his story to Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America members and Tuttle found the “campaigning” distasteful.

In an interview in the defunct Fantastic Metropolis, Tuttle was asked of about her genre of choice. She explains, “I’m attracted to the intellectual aspect of SF—I like fiction which deals straight-forwardly with ideas, fiction which is intellectually stimulating and questioning. I like the idea of SF as ‘thought-experiment’—although mostly in a social and personal sense. I like trying to figure out what it would FEEL like to be immortal, for example, or to live in a society with dramatically different values and ideals than our own.”

George Eliot, Romola

The historical novel by Eliot is set in Renaissance Florence, just after Christopher Columbus has left Spain. There is a blind scholar, his titular daughter, an estranged brother who is a Dominican friar, a shipwreck, enslavement of adopted fathers—the works. Eliot apparently spent a year and a half researching for the book. She often went to Florence in order to capture the story. While she received £7,000, the book apparently didn’t sell well. This despite the fact that Eliot herself said of writing Romola that she did “swear by every sentence as having been written with my best blood, such as it is, and with the most ardent care for veracity of which my nature is capable.”

Kristen Ringman, I Stole You: Stories from the Fae

In its review of I Stole You, Publishers Weekly states, “Ringman (Makara) has woven her recollections of personal experiences with ‘fae creatures’ into these 14 lyrical, disturbing first-person tales, all told to victims by vampiric shape-shifting beings drawn from various mythological traditions. Ringman, who is Deaf, postulates telepathic fae-to-human connections as well as signed communication with emotional overtones that no auditory vibrations can match… Ringman successfully brings readers a few steps out of everyday reality.”

Julie Otsuka, The Swimmers

Otsuka’s novel introduces us to a group of people who know one another through their routine of swimming. The NPR review of The Swimmers explains, “When the pool is shut down for safety reasons, the collective daily rhythm of the swimmers’ lives abruptly stops. One swimmer is particularly affected by this rupture in the pattern of the everyday: her name is Alice, ‘a retired lab technician now in the early stages of dementia.’ We’re told that, ‘even though [Alice] may not remember the combination to her locker or where she put her towel, the moment she slips into the water she knows what to do.’ Untethered from the practice of those repetitive daily laps, Alice’s mind floats free. The Swimmers is a slim brilliant novel about the value and beauty of mundane routines that shape our days and identities; or, maybe it’s a novel about the cracks that, inevitably, will one day appear to undermine our own bodies and minds.”

Maru Ayase (trans. Haydn Trowell), The Forest Brims Over

The first of Ayase’s works to be translated into English, The Forest Brims Over fights the usual gender tropes in myth and storytelling when Nowatari Rui turns herself into a forest to avoid her husband using her as inspiration for his novels. As the jacket copy states, “With her privacy and identity continually stripped away, [Rui] has come to be seen by society first and foremost as the inspiration for her husband’s art. When a decade’s worth of frustrations reaches its boiling point, Rui consumes a bowl of seeds, and buds and roots begin to sprout all over her body. Instead of taking her to a hospital, her husband keeps her in an aquaterrarium, set to compose a new novel based on this unsettling experience. But Rui breaks away from her husband by growing into a forest—and in time, she takes over the entire city.”

Noor Hindi, Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow.

Hindi’s poem “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying,” made rounds when it was first published in Poetry in late 2020 and is understandably being posted on social media again and again since Israel’s brutal assault on Gaza. “I want to be like those poets who care about the moon,” she writes. “Palestinians don’t see the moon from jail cells and prisons.” The intensity of this poem seems to be the general tone of the forceful collection. Viet Thanh Nguyen says of Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow., “Noor Hindi wields her poetry with passion and righteous anger in this powerful, striking collection that touches the heart and the head, the body and the mind.”

Cassandra Khaw, The Salt Grows Heavy

Becky Spratford in her starred review of Khaw’s book in Library Journal, states, “What if the Little Mermaid laid eggs and her hatched children’s hunger laid waste to her prince’s land? Khaw’s (Breakable Things) latest novella tackles this question with a brutally visceral but seductive opening sequence.” Spratford’s verdict? “With this brilliantly constructed tale that consciously takes on a well-known story and violently breaks it open to reveal a heartfelt core, Khaw cements their status as a must-read author. For fans of sinister, thought-provoking, horrific retellings of Western classics by authors of marginalized identity like Helen Oyeyemi and Ahmed Saadawi.”

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Dictee

Cha was an artist and author whose book, Dictee, while receiving only tepid responses upon its publication in 1982, resurfaced in the 1990s and had continues to have an enormous impact on writers, readers everywhere. In her book Minor Feelings, Cathy Park Hong writes extensively about Dictee. She states, “Although it’s classified as an autobiography, Dictee is more a bricolage of memoir, poetry, essay, diagrams, and photography.”

In 2022, the New York Times published an obituary for Cha as part of its “Overlooked No More” series. In it, Dan Salzstein writes of Dictee, “Through chapters named after the Greek muses, the book jumps from one protagonist to another: Cha herself; Joan of Arc; the early 20th-century Korean freedom fighter Yu Gwan-sun, who, at 17, was tortured and killed; and, perhaps most poignantly, Cha’s mother, who hovers over the book like a protective spirit. Through her, Cha explores a traumatic era of Korea’s history, including a decades-long Japanese occupation, a war that divided the country, a series of dictators and an ensuing diaspora, of which the Cha family was a part.”

Jeanette Winterson, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit

Born in 1960, Jeanette Winterson was adopted by a couple in England. By her own description, her parents were working class, with a father who was a factory worker and her mother a home maker. “There were only six books in the house, including the Bible and Cruden’s Complete Concordance to the Old and New Testaments,” Winterson’s site states. “Strangely, one of the other books was Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, and it was this that started her life quest of reading and writing.”

Winterson’s parents were raising her to be a Pentecostal missionary, and, by the age of six, she was writing sermons and preaching. Ten years later, Winterson came out as gay and left home. She worked at a “lunatic asylum” to make ends meet, before going to Oxford and studying English Literature. By 23, she had written Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, a semi-autobiographical novel about her young life.

Cleo Qian, LET’S GO LET’S GO LET’S GO

Qian’s debut short story collection has received a heap of praise, including being longlisted for the Carnegie Medal for Excellence. In an interview with A. Cerisse Cohen in BOMB, Qian explains, “I wrote these stories from 2016 to 2022. In my own life, I was experimenting and testing out new identities all the time. I thought a lot about subject matter. There are many people who find literary fiction insular and narrow. I think part of the writer’s duty, in addition to being good at your craft, is to live and think broadly. Otherwise, who are you writing for?… My stories are often about characters who feel disembodied, which I also feel. I didn’t realize that until I started doing yoga and the other physical activities I mentioned. We’re glued to our phones. I write and read a lot, which is also all in my head. I have friends who are cerebral and intellectual and so fun to talk to, but we’re not very connected to our bodies. That’s unnatural. We should all be more in touch with our bodies.”

Nalo Hopkinson, The Salt Roads

Gregory E. Rutledge, in his review of Hopkinson’s book, writes, “The Salt Roads features three mortal protagonists—Mer the Ashanti-born, Santa Dominque-enslaved healer, Jeanne Duval, the mulatta lover of Charles Baudelaire, and Thais, a sex slave of ancient Alexandria, Egypt—who are bound by the bitterness of life and the salutary potential of the meandering, salty flows of the earth, which a fourth immortal protagonists represents.

Just as former Black fantasy author Charles R. Saunders recognized in Butler a true raconteur in 1984 (Bell 91), the label easily applies to Hopkinson, who manages some powerful storytelling here. What author wouldn’t when she expertly excavates the ancient Roman empire located in Alexandria, Egypt, and the Holy Land of Jerusalem, walks readers through Napoleon’s empire in France and the West Indian French colonies, and includes a fist fight, of sorts, between two West African deities of fire and water?”

James Tiptree, Jr., Her Smoke Rose Up Forever

For the uninitiated, James Tiptree, Jr. was in fact Alice Bradley Sheldon, a woman who invented the name based on a marmalade brand after years of unsuccessful attempts at publishing with versions of her own name. “A male name seemed like good camouflage,” she said. “I had the feeling that a man would slip by less observed. I’ve had too many experiences in my life of being the first woman in some damned occupation.” This is because Sheldon had a wild life—she eloped, had to drop out of unmarried-women-only Sarah Lawrence College, took classes at Berkeley and made art, divorced, joined US Air Force and was promoted to major, met second husband in Paris, joined the CIA, finished college, got a doctorate. Whew! Her pseudonym successfully kept her anonymous for about a decade.

John Self writes in The Guardian, “Tiptree’s status as one of [science fiction’s] leading practitioners is justified, as is the critical cliche that each story contains enough to fill a novel. That’s not unqualified praise: Tiptree’s techniques of defamiliarization through jargon… and dropping us in medias res means the reader has to remake the world with every new story. But in the darkness of space no one can see you scratch your head and given that most of the stories require two readings to be properly absorbed and appreciated—and they merit that attention.”