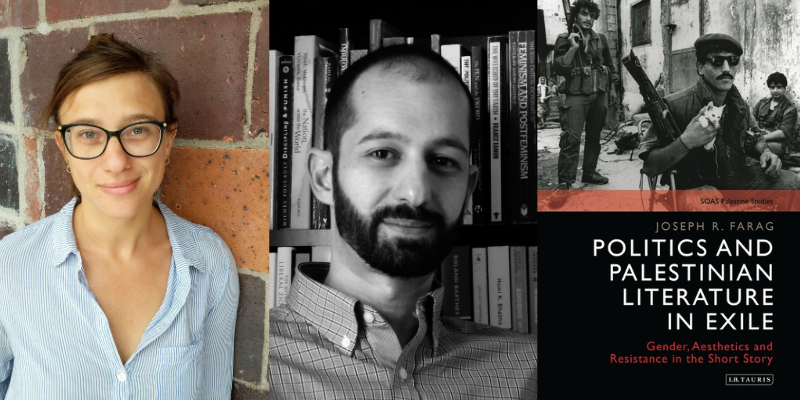

Shir Alon and Joseph Farag on Palestinian Literature

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

In the wake of the recent violence in Palestine and Israel, the show returns to an interview taped in June 2021 with scholars Shir Alon and Joseph Farag, who join co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss how Palestinian and Israeli writers have written about the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. Farag talks about the evolution of the portrayal of the Palestinian self in literature throughout history, as well as some of the themes and writers discussed in his book, Palestinian Literature in Exile: Gender, Aesthetics and Resistance in the Short Story. Alon explains how the unprocessed trauma of the history of massacre and expulsion of Palestinians seems to stage an appearance in Israeli literature every decade. She also talks about Dolly City by Orly Castel-Bloom, Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, and Funeral at Noon by Yeshayahu Koren.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Andrea Tudhope and Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: I think in American literary culture, the general impression of prominent Israeli fiction writers like Amos Oz has been that they are critics of the occupation and the Israeli government and military. First of all, is that true? And secondly, who are the other [writers] of Israeli and Palestinian literature that we should be paying attention to as readers?

Shir Alon: To begin, even the American perspective of the Israeli left wing is far more conservative than anything that is actually considered left in Israel. And I would say that writers like Amos Oz — who is usually read together with David Grossman and A.B. Yehoshua, as this kind of trio of liberal Israeli politics — did represent a mode of critique of the occupation since ’67. But in order to clarify this, we have to do a little bit of history. So Joe [Farag] was talking about the Nakba, the expulsion of 1948. The second term Sugi asked about was the Naksa, which is literally translated to “withdrawal” in Arabic and refers to the 1967 War, which is when Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza and the Golan Heights and basically established this ongoing illegal occupation, a lack of established state borders, and a process of settlement building, which is not recognized by international law. Now, I think this historiography is important for literature as well. We see a difference between the literature of the period between ’48 and ’67, and the literature that comes after that.

WT: What is that difference?

SA: It’s a long answer. Some of it we’ll get to a little bit later. But in the literature leading up to ’67, you really see Hebrew literature writing itself as settler colonial literature. It is asking itself, how do I establish myself in this space? It is seeing the ruins of Palestinian villages around it, and it must articulate a position in relation to them that also explains Jewish sovereignty in relation to the Arab minority and to the Palestinians who are gone, who have been expelled. After ’67, especially in the ’80s and ’90s, and when the Intifada, the Palestinian uprising, begins, this political energy turns to the occupation and to protesting this form of control of a huge population that are not citizens, that do not have any sorts of citizenship rights, as a kind of a solution to the anomaly, which is the Israeli state. And questions about the Nakba, about 1948, about the original expulsion, are, to a large extent, overlooked. Now, in the past few years, it is impossible to ignore them again. There’s a lot of complex political dynamics going into it.

WT: That was really great. Now, I’m going to lead you back to Amos Oz. But that was very helpful. Thank you for doing that.

SA: Oh, of course. Amos Oz really represents a generation in Israeli writing that comes out of this settler ethos of ’48 and feels somewhat betrayed after ’67. Because suddenly, the state that they identify with is engaged with these explicit atrocities and illegal occupation, because of demographic changes within Israel that have to do with relationships between Mizrahi Jews — Jews of Middle Eastern origin — and Ashkenazi Jews. And Amos Oz’s writing represents this nostalgic yearning to this period of innocence when the state was small, when the Arabs were obedient, when men were men and women were women. Absolutely he was a very important voice against the occupation of ’67 as a means of reestablishing the righteousness of the Israeli state within its ’48 borders.

Joseph Farag: Which is kind of ahistorical, to go back to what you were saying earlier, given that previous stage of Israeli writing, which was much more forthright about confronting that 1948 to 1967 period and the settler coloniality of that. My favorite work of literature on this is actually Theodor Herzl’s Altneuland, which is published in [1902], and is completely unabashed about the colonial nature of what he calls the new Jewish society in Palestine — he didn’t even refer to it as Israel at the time. But he makes very clear that this will be a wonderful boon to the world’s imperial powers — we will develop cures to malaria here that will allow Europe’s imperial powers to venture into the great African “heart of darkness,” because we will break that final fetter of malaria, preventing greater colonial incursion into Africa. And so, this new Jewish society was seen as a kind of integral part of that settler coloniality, and from my more cursory knowledge of Israeli writing, there was a period where that was pretty frankly addressed.

SA: I do want to say, when we speak about Israel as a settler colonial society, it sounds very radical right now, like a new framework, but this was very explicitly the way the settlers saw themselves. Their model was a colonial movement, they called the settlements colonies. There was nothing that was secretive about it as a model by which the state was imagined. Of course, Zionism is very different as a settler colonial movement because it doesn’t have a metropolis, because it’s a settler colonial movement of refugees. So it has its specificities. But, when we use this language right now we should remember that this is also the language that was used up to the ’50s.

WT: Well I live in Kansas City… this was a settler colonial society around the Santa Fe Trail! Joe, just to finish off this question, Shir gave us some of the very famous Israeli writers—maybe you could talk to us a little bit about who are the great Palestinian writers that from this period should be listened to, right or wrong?

JF: I always fear reifying the canon—if you just name the same authors that everyone’s already talking about, then you contribute to that further entrenchment. But, there are these periodizations in Palestinian literary history that have their particularly notable figures. And so in the 1948 to 1967 period, Palestinian literature — and this is very broad strokes, there are exceptions to this, certainly — conveyed the Palestinian experience of being one of abject exile refugeehood, at the mercy of the “host state” that housed the refugee camps … almost an articulation of victimization primarily. After 1967, it’s impossible to overstate how gargantuan the defeat of the Arab armies was in 1967, where the combined armies of Egypt, Jordan, Iraq and Syria were, within a matter of hours, handily defeated by the Israeli military. So all of the hopes that Palestinians had pegged onto the Arab states and their vaunted armies to liberate them were dashed. And there was this deeply iconoclastic moment that necessitated a Palestinian reinvention of self. And it’s no coincidence then that in 1968, we have the rise of Palestinian armed resistance movements, which had been operating sporadically here and there in the years leading up to it. But from 1968 onwards, you see a sustained armed resistance movement and multiple different armed factions emerging.

And so, literature responds by reconceiving the Palestinian self from one of being an abject victim into one of a heroic resistance fighter. And this plugs in at the same time as the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, you have Algerian independence struggles happening, you have this kind of global, “third world,” anti-imperialist foment that’s taking place and Palestinians, during this period, see themselves as part and parcel of that global movement. And so once again, this anti-colonial, anti-imperial ethos reasserts itself. And the iconic figure of the Palestinian goes from being the abject refugee to the kofia-clad resistance fighter with the Kalashnikov. That comes to be reflected in the literature, but also, Palestinian literature doesn’t take the figure of the Palestinian resistance fighter during this period too seriously. There was a lot of skepticism towards the potential of the armed resistance to actually deliver national independence and sovereignty

WT: Who are some of the writers you’re thinking about from that period?

JF: In the earlier period — I include him because he was really the first exponent of this ethos of resistance — you have Ghassan Kanafani, probably the most iconic, the most canonical of Palestinian prose authors. Mahmoud Darwish is the most iconic Palestinian poet. There’s Jabra Ibrahim Jabra. You also have starting in the late 1960s, early 1970s, the emergence of validly and outspokenly feminist Palestinian authors like Sahar Khalifeh and Liana Badr, who were some of the most barbed critics of Palestinian armed resistance. With the Algerian case not far in the background, where Algerian women played a key role in resistance and then were relegated to the domestic sphere and were horribly marginalized generally, there was a concerted effort by Palestinian feminists and feminist authors in particular to not further lionize the very masculinist vision of national independence movements, central to which, of course, was the armed, predominantly male Palestinian resistance fighter. I don’t want to neglect the fact that there were female Palestinian resistance fighters, Laila Khalid being the most iconic example. Women did certainly take a more prominent role in armed resistance beginning in the 1960s, but the response of a lot of feminist authors was to be skeptical about this very patriarchal, macho, nationalist movement.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: I feel like it’s predictable that I’m fascinated by this, as someone who writes about Sri Lankan Tamils. When I was reading your work, listening to you talk, Shir, you mentioned Amos Oz as someone nostalgic for the 1948 to 1967 period of “greater innocence,” the smaller state. And then Joe, when I was reading your work, you were talking about a generational Arab critique of people post 1967, critiquing their elders as people who had been, Shir, I think you used the word obedient. So the conversation going on between these literatures is so interesting. When we were talking before this conversation, of course the Nakba is this massive trauma, and I think people think of it as a Palestinian trauma, and of course it is. And then Shir, you said to me that it was also a trauma for Israelis. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that and about discovering the Nakba, again and again, in Israeli literature.

SA: So, when I say the Nakba is a Jewish Israeli trauma as well, I’m speaking about trauma as a structure. We usually associate trauma with victims, with victimhood, but the fact is, trauma is a threatening experience that the self does not want to process, and it remains unprocessed, it remains repressed. And then, as Freud writes, what happens is this repressed content inevitably returns. The principle of return is this obsessive repetition and obsessive chewing over these materials that you’d rather not deal with, you’d rather shove down. And we see something very similar in Hebrew literature and culture, particularly in this early period of the 50s up to the 70s.

In 1948, the expulsion of the Palestinian was a known fact, and we see it very clearly and explicitly in literature. The poet Nathan Alterman wrote poems about this, journalistic poems where he’s very clearly chronicling the massacre of Palestinians in Lydda [Lod], where there were a lot of riots and violence just a few weeks ago. There is a very famous novella called Khirbet Khizeh by S. Yizhar, who was a fighter in the ’48 war, he later became a politician. It’s a magnificent text that narrates the expulsion of the Palestinian village from the point of view of a soldier. And there is nothing that is secret there, it’s all very clear, he looks at the village and he says, we are creating a Holocaust. He looks at them, he sees the Jewish refugees from Europe from just a few years earlier. This novella was a bestseller. Nobody thought this was something that was hidden. But in years afterwards, the story of the expulsion was denied, both passively, people didn’t talk about it, but also very actively. There were hundreds and hundreds of Palestinian villages where their citizens were expelled, or they ran away and were not allowed to come back.

In the ’50s, Israel starts a campaign to destroy these villages, to not leave them there as monuments to the destruction. Very famously, in a lot of places, forests were built over these ruins. Maps are changed, names are changed. And there is a very big campaign to change all the names of towns or geographical markers or historical markers to their Hebrew names that completely erase the Palestinian layer of this geography. And what happens is that, in 1967, you have a story like Facing the Forests by A. B. Yehoshua, a very famous novella as well, in which you have a grad student who needs to finish his dissertation — this might be familiar to a lot of us. He takes himself to some writing retreat in the woods, and it turns out that under the woods, there are the ruins of a Palestinian village. And he’s not aware of that, and the woods have to be burned down in order for this village to be revealed. So something that was common knowledge — the Nakba, the Palestinian catastrophe, the expulsion — is staged in this literature as a story that is hidden and has to come to light. In another book that I’m writing on now, which is not as well-known, but I wish it was, called Funeral at Noon by a writer called Yeshayahu Koren. It was written in ’66, published in ’74. This is a settler colonial text, because it’s so obsessed with marking the land and marking the geography, and it takes place in a small Israeli colony by the border. And right next to it there are ruins of a Palestinian village, and it’s called in the very first line “the abandoned Arab village.” I heard an interview with the writer Yeshayahu Koren once, and he said, ‘nowadays everybody’s making a big deal that this is happening in a Palestinian village, but I didn’t even think about that the village was just, you know, part of nature. The history is unseen.’ And, you know, you listen to him, and you say, what do you mean it doesn’t mean anything? Of course this is about the Palestinian village. The novel is about this dissatisfied housewife that keeps returning again and again to this destroyed village, and she doesn’t really know why, but that’s where she goes in this obsessive return to this moment of constitutive violence of the state. But when Yeshayahu Koren wrote it, the Palestinian village was not associated at all with this history, even though it’s right there in the middle of the text. So it has this capacity to disappear.

We see the cycle happening again and again. Literature, every few years, stages the discovery of the Nakba. The repressed comes up, and then it’s just acting out. There is no working through, there is no actual work of decolonization, of, ‘okay, what does it mean that our lives are built on ruins? What does it mean that our homes were somebody else’s homes?’ It is just shoved under the carpet again to reemerge 10 to 15 years later.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Andrea Tudhope.

*

Static: Labor, Temporality, and Literary Form in Middle Eastern Modernisms (forthcoming book) • “The Ongoing Nakba and the Grammar of History,” LA Review of Books • “No One to See Here: Genres of Neutralization and the Ongoing Nakba” • “Gendering the Arab-Jew: Feminism and Jewish Studies After Ella Shohat”

Palestinian Literature in Exile Gender, Aesthetics and Resistance in the Short Story • Teaching with Arabic Literature in Translation: ‘Palestinian Literature and Film’

OTHERS:

An Open Letter in Support of Adania Shibli From More Than 350 Writers, Editors, and Publishers, Literary Hub •“Tension Over the Israel-Hamas War Casts a Pall Over Frankfurt Book Fair,” by Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth A. Harris, The New York Times • The LiBeraturpreis 2023 (press release by Litprom) • “We want to make Jewish and Israeli voices especially visible at the book fair” | Frankfurter Buchmesse • “Palestinian voices ‘shut down’ at Frankfurt Book Fair, say authors,” The Guardian • Amos Oz • David Grossman • Facing the Forests by A. B. Yehoshua • Khirbet Khizeh by S. Yizhar • The Old New Land (Altneuland) by Theodor Herzl • Men in the Sun, Palestine’s Children: Returning to Haifa and Other Stories, and All That’s Left to You: A Novella and Other Stories by Ghassan Kanafani •”A Lover from Palestine,” “ID Card,” and many others by Mahmoud Darwish • The Ship by Jabra Ibrahim Jabra • Wild Thorns and Passage to the Plaza by Sahar • Eye of the Mirror and A Balcony Over the Fakihani by Liana Badr • Nathan Alterman • Funeral at Noon by Yeshayahu Koren • Minor Detail by Adania Shibli • Dolly City by Orly Castel-Bloom • The Sound of Our Steps by Ronit Matalon • Waltz with Bashir (film) by Ari Folman • The Pessoptimist by Emile Habibi • Divine Intervention, The Time that Remains, and It Must Be Heaven (films) by Elia Suleiman