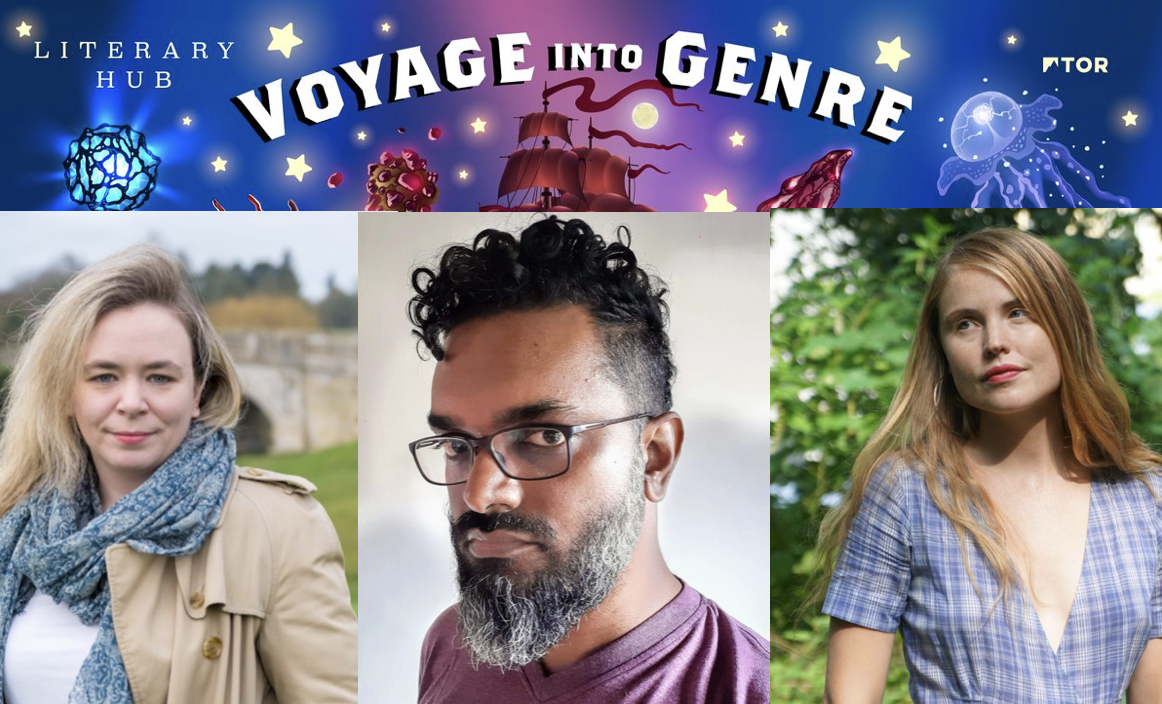

Questioning Authority and Story: Emily Tesh, Vajra Chandrasekera, and Sophie Strand

Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre S03E02

Tor Books, in partnership with Literary Hub, presents Voyage Into Genre! Every other Wednesday, join host Drew Broussard for conversations with Tor authors discussing their new books, the future, and the future of genre. Oh, and maybe there’ll be some surprises along the way…

It’s near impossible, I think, to not question authority these days. Maybe that’s the wannabe punk rocker in me, or maybe it’s the fact that so many of the things I was taught as a child (about history, about economics, about humanity) are turning out to be made up and my generation (not to mention the ones younger than me) are left holding the bag while the teachers ride out their last days in relative continued comfort.

We’ve got to interrogate these structures that have been taken for granted, and what better way to do that than through fiction? Especially genre fiction!

This week, Emily Tesh takes us to Gaea Station for Some Desperate Glory and the necessary difficulties of writing about fundamentalism, the eerie feeling of watching the AI conversation arrive much more quickly at the novel’s related questions than she expected, and some lessons from human history. Then, Vajra Chandrasekera talks about blurring all of the expectations of genre in The Saint of Bright Doors, using his fiction to write an anthropology of the present day (even when it takes place in an alternate world), and telling exactly the kind of story he wanted to tell. Finally, eco-feminist writer and scholar Sophie Strand (The Madonna Secret) offers a new way of considering Christianity and urges a return to community in the way we encounter story.

See you in two weeks,

Drew

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

Read the full episode transcript here.

*

Emily Tesh on Trusting the Reader and Anti-Heroines:

A lot of it when I was writing it came down to asking myself, how much do I trust the reader? And of course that’s quite a big question cause you don’t know who’s going to read the book. You can hope that reader will be someone who’s heard of unreliable narrators, or a person who’s willing to give a unlikeable narrator a go.

And I got that word a lot. “She’s so unlikable.” “Are you sure she’s not too unlikable?” “I think it’s very brave to write about a girl who’s not likable.”

And I thought, Hmm, I bet you’ve read plenty of anti-hero books with a unlikable hero and never asked this question.

So some of it was spite a little bit, being like, you know what? I am just going to write an anti-hero who’s actually an anti-heroine, somebody with genuinely unpleasant dislikeable qualities but I was interested in how a person can be both a villain and a victim at the same time. Just because someone is a bad person–and I do think Kir at the start of the book is a pretty bad person–doesn’t mean they’re not a human being.

So I was interested in that compassion, if you like, for the person who is the worst.

I think as well, the thing I said about trusting the reader, one does occasionally see, and social media is terribly chilling for a writer, readers who give no grace at all. And I knew that some people reading Kir would give her no grace at all and would say, well, this is a book about a character with fascist beliefs and therefore I have no interest in seeing what happens or why it’s been written that way or what else there is but I hoped that most readers would be able to feel the dissonance between what Kir believes and what’s being done to her. I hope it’s clear that she’s an abuse victim. And she’s an abuse victim, so thoroughly indoctrinated that she can’t even bring herself to see what’s been done to her because it would be unbearable. It would start a cascade that she can’t face.

*

Vajra Chandrasekera on the Blurring of History and Mythology, Our World and Another:

I think I set out more or less explicitly not to create a secondary world. I think it gets taken very much as a given of fantasy. Like this is how fantasy is supposed to work, you’re supposed to create a world that is different from ours and sometimes you may have like portals or like some kind of travel between our world and the other one, or else it’s a secret world hidden underneath ours. Like you have the vampires and the werewolves in the subway tunnels or whatever.

But I wanted to do something a little more, um, well for me, I began it with kind of a South Asian setting, right? ’cause I’m from Sri Lanka and, I’m actually not sure how much of what feels alien, strange to a Western reader, how much of that is just South Asia, and how much of that is fantasy?

For me it was an attempt to bridge the things in a fantasy which are supposed to be recognizable or supposed to be almost recognizable versus the things that are supposed to be entirely made up or fictional or imaginative.

There’s a kind of blurring of history and mythology, which I think is very familiar to South Asian readers because our histories tend to roll backwards. And if you just keep going backwards eventually, you’re in straight up mythology, right? Like, magical things are happening.

The line between the two can be very, very blurry and that blurriness is also highly politically significant depending on whose mythology is being forced onto who. It’s very much a book about history and the way histories are formed, structured, organized, and recorded.

*

Sophie Strand on the Need for Oral Storytelling:

90% of human history was oral and in an oral culture, knowledge never belongs to a singular author or to a singular telling. It’s kept alive by a constant resurrection, vocally, relationally in a community of people. And every time it’s brought back, it’s told differently to suit a specific moment. The thing that happens when we switch into written text is stories become objects and they become objects that can’t respond, can’t adapt, can’t be questioned, and don’t change.

And for me, that’s the real danger, is that people somehow think that this one account could somehow be useful to us today in a different ecosystem, in an entirely different place. Storytelling needs to evolve, just like bodies need to evolve, and it evolves through bodies, through orality, through a kind of interstitial weaving between audience and teller.

______________________

Tor Presents: Voyage into Genre is a co-production with Lit Hub Radio. Hosted by Drew Broussard. Studio engineering + production by Stardust House Creative. Music by Dani Lencioni of Evelyn.