In Praise of Destruction: How Embracing Elimination Can Make Our Writing Better

Stephanie Bishop on Losing a Manuscript, Starting Over, and Learning to Swing a Literary Wrecking Ball at Her Work

I’m wary of those writers who tell me, with absolute certainty, that all I need to do is make a decision. They are referring to the book I’m trying to write, a novel that does not know where it’s going, or what it’s about. A novel, I say, or the novel—because it seems its own singular thing, and as if it has (almost, in a way) its own consciousness, which it is my job to deduce and come to know. This other type of writer, the one in favor of decision making, refers to their own project as “my book.”

First-time novelists tend to do this: assert possession, lay claim to the object, as do writers of a certain bent—the ones who own the project sufficiently to impose decisions. I sometimes envy this. For such writers, a novel-in-progress exists as an accumulation of positive choices: it is this, and this, and this.

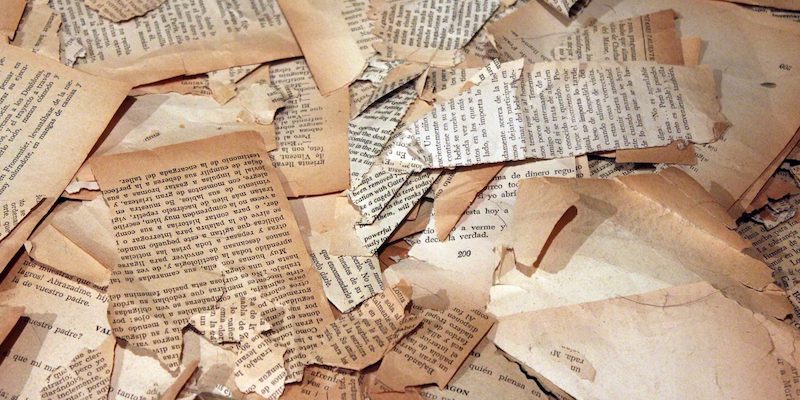

It took the loss of a draft manuscript to make me realize that I work in the opposite direction: by a process of elimination and outright destruction. I was in the midst of lockdown, there were two children to be home-schooled, I had university classes to teach and a book to edit. My computer was old and slow but we couldn’t afford a new one and in a harried attempt to free up space I rushed through, deleting what I assumed was old student work. I mistook the title of my own early draft for someone else’s project and wiped it clear off the system.

Normally methodical in my backups, there turned out to be an inexplicable glitch where the particular file with that document was nowhere to be found, although every other draft file of everything I had ever written was there. I wept for days. I searched and searched again. I phoned tech experts. Nothing. And so I started again. But I couldn’t re-create those scenes, although I knew what some of them were. Making the decision wasn’t just not enough, it was nowhere near. Scenes couldn’t be retrieved, re-built, re-worded.

The process might be more straight forward if I could just make one positive decision after another, but the result is writing that feels stunted—merely the sum of its parts. Starting again was starting anew, and this time it came with a far greater awareness of what that meant, and of how different that task was from laying out the pieces and putting them together. A task of de-creation, undoing, myriad forms of riddance.

To choose against, to write away from, to not know, to delete, to work by way of elimination, to write in opposition. To write what you don’t know, or towards what you want to know, or into what you can’t seem to figure out. This is the first instinct. The second is to set the parameters for the project by knowing what it is not (what it can’t be, what I don’t want it to be, what it seems not to want to be, what the instinct refuses to engage with).

I want a contract with no inclusions, no inherited aesthetic I must work around, a desire fueled by an acute awareness of the many things we are meant to be in our daily lives, and the many attributes a novel is expected to have.It’s not a boy-girl story, not a sad-girl story, not an ironic story, not a satire, not a quest, not a fantasy, not an epic, not a historical narrative, not a prose-poem, not a multi-generational saga, not a novel with a city in it, not a novel with boats or airplanes or trains or even many cars, not a wedding story or a funeral story, not a party story.

The process of creation is one of concentration, deduction, elimination: detective work in which likely suspects, likely players, are assessed and ruled out, or else tested further. There is an aesthetic inclination here too: to rid the writing of anything superfluous, to work as close to the bone as I can. Which means to find the bone, stripping everything else back. To delete and compress. Why can I not think about the positive shape—the thing it is? Wouldn’t this be easier?

Easier doesn’t mean more fun, or more compelling: the process evolves into its own puzzle, something like the thrill of the chase. There is a loosening of energy that comes with doing away with things, refusing, clearing the path. An alchemical process occurs by boiling the shit out of the soupy mess until it reduces to a near pure burst. I want a contract with no inclusions, no inherited aesthetic I must work around, a desire fueled by an acute awareness of the many things we are meant to be in our daily lives, and the many attributes a novel is expected to have—how we are obliged in a routine way to perform our positive attributes and strive to create a positive outline in the world, a positive experience on the page: a novel that is gripping or fun or moving, etc.

We are primed, in an uncomfortable way, to be always ready to say what it is “about,” long before we really know what the answer to this question is. In truth, the bulk of the time spent drafting a novel feels like floundering around in a dark building, running my hands over the walls to feel for a light switch: what even is this, where am I? The novelists’ creative energy hinges on the experience of un-classifiability, on the plunge into not-knowing. That not-knowing has a shape, marked out by all the refusals, the impossibilities, the choices that would be wrong choices were they to be followed though.

I start wide, work inwards: not that, this, not that, this, not that again: the sorting table of the mind. I am a single woman, multi-eyed ogre-faced spider of a search party, spread out to comb the long grass. Is this a clue? No. Is that a clue? Maybe. This, not that. Not that, this. Not that, not that, not that, no. In this way I start to create a stabilizing framework that allows for maximum states of not-knowing, the parameters of a form inside of which discovery can occur.

One layer of refusal starts to build on another. To say no to one thing—so as to get closer to the yes—means you must have said no to something before this: an endless wavering chain. We are told that is not how we should live: one should move towards the thing one wants, act in favor of something, lean in, go hard, etc. But given I don’t know what that something is, I do the prep-work. I clear the space. This is not an easy, polite tidying. It takes a slash and burn, a savage ground fire, a bulldozing. Rules for others. Refusals. A lock on the door, late meals, a chaotic house.

You clear the space once, then you clear it again, and every day you do the same thing. You clear the hour, the two hours, whatever time is there. You wear the noise-cancelling head-phones, you shoo people away. You say: Nothing else, even if there is nothing to say. You hold it open, like one of those caricatures trying to press the closing walls away from them. You make sure there is nothing so that there can be something.

And it doesn’t matter, if there was something there yesterday. The weather changes. Whole systems free fall in collapse. When you were a child you remember being fascinated by the backburning undertaken in the bush, ahead of each summer: how men would walk out into the wild in their orange suits lighting line after line of low burning fires, the flames glowing and flickering long into the night, marking out the space inside of which life was meant to go on, undestroyed, green and living.

The instinct is to destroy the impulse to destruction: to shut it down, to avoid what might register as self-sabotage. But sometimes it is the only way.If I were to try to break it down and classify the stages of destruction—the kind of destruction that means you eventually reduce the field of possibility until it becomes little more than a thin highwire along which you must walk—I would say it goes like this: You do away with the big things you do not want the work to be, or the things the work seems to refuse to be—questions of genre, time period, broad themes or subjects. You kill off the half-formed characters, the ones who linger in the margin without moving or feeling or evoking something in others. You close your eyes and feel around in the dark space of the project: where am I, you ask?

You’re trying to make out a landscape in the fog and murk. Is it the coast? Is it a mountain range? Is that sound the hum of the city, or could that be the ocean? You set out into it, ready to correct and edit your hunches: This not that. That, not this. You listen carefully for a sound to follow into the dark. Only you realize, after a time, that you have gone the wrong way. You have chosen the wrong adventure. You have hit a dead end.

This triggers a phase of mass deletion, the staring into space, the labelling of new documents, the cutting up pages and spreading them out paragraph by paragraph on the floor. You do the whole thing again. And maybe again. And maybe again.

A novel in progress is a cluttered, messy thing, at least in terms of how it exists in your head. And there are so many ways for that mess to be made, and it’s much harder to make it tidy and organized. A novel in progress, is by definition, a disorganized system: one that seems to resist its own reorganizing, that clings to its own redundant parts, that is comprised of an almost infinite variability of patterns. The chaos stakes are high. In the drafting process one moves from higher chaos and lower complexity, to higher complexity with lower chaos. Expel, delete, expel, delete. There is only so much control one can assert: in the early stages the reigns are held tight: there is the false belief in the power of “making the decision”—playing the author.

But once you are far enough inside the chaos, the energy of the work takes over. What cannot be there cannot be there. What must be there must be there. The only way towards this is through radical demolition.

Much of this is deliberate. But at a certain stage destruction of a different order occurs. At some point the wrecking ball comes; an involuntary given-by-the-universe kind of destruction that is forced upon you. The wrecking ball smashes its way through the artifice of whatever thing you’ve been diligently carving: the precarious structure built over a sinkhole, the delicate story, the well-crafted protagonist, the coherent narrative. The wrecking ball smashes through whatever you have been trying to write in order to cover over, or avoid, or find a detour around the stuff that keeps trying to push its way through and which you cannot—for whatever reason—see clearly.

The strange or unpredictable or unwieldy story, the story you were trying to write yourself away from, the story you didn’t want to have to wrangle with and understand, that you were afraid of because you thought you couldn’t understand. The wrecking ball swings through once, twice, three times. Demolition will be insisted on. The ground cleared by whatever devious means—mysteriously deleted files, mis-directions, a dream, an error, an accidental conversation, a lost notebook—so that the other thing might be written.

The landscape changes. The water table creeps up and rises through the surface, softening the ground, flooding the consciousness: destruction as a subtle, seeping, dissolving power in the making of a work, an unwilled experience.

The instinct is to destroy the impulse to destruction: to shut it down, to avoid what might register as self-sabotage. But sometimes it is the only way. You give in to whatever insists on being said until the long straight road of the work opens up before you and you put your foot to the pedal and tear through the strange clear landscape.

______________________________

The Anniversary by Stephanie Bishop is available via Grove Atlantic.