Writers and Liars: On Fact, Fiction, and Truth

Leslye Penelope Considers the Line Between “Truthy” and Truth

I’ve often heard authors say that fiction is merely lies. George R. R. Martin has said that “we’re writing about people who never existed and events that never happened…[a]ll those things are essentially untrue.” Norman Spinrad characterizes these fictional lies as differentiating the genre from “biography, history, or reportage.” The list of writers with this viewpoint goes on and on. There’s even a fiction writing group, for whom I once had the pleasure of being a guest speaker, called the Pocono Liars Club.

It’s not hard to understand this perspective. As a novelist, I do make things up for a living. But I believe the job of the author is to tell emotional truths, and that the best way to do that is rarely by relaying facts and figures or repeating events just as they happened. Journalism and documentaries have an important place and often use the same toolbox as fiction does, however, fiction is uniquely suited to truth-telling because humans have storytelling baked into our DNA. We understand the world best through stories, and these are an incredible way to arrive at something approaching a universal truth.

On a technical level, fiction writers must contend with the difference between realism and verisimilitude, or the quality of appearing to be true.In college, I became obsessed with the quote from Don Quixote, “Facts are the enemy of truth.” I stenciled the words on my backpack and had many conversations with friends, acquaintances, and nosey passersby about what exactly it meant. Two decades later, as I wade through the quagmire of a media landscape in which “alternative facts” are a thing, I come back to what I think Quixote was trying to convey—does evidence or proven information have any bearing on the truth? With so many people across the political spectrum eschewing science in favor of ideology, perhaps it really only is in fiction that we can find a common understanding of reality.

When we want someone to truly understand something, we turn it into a story. Public speakers often break down their information into anecdotes or elaborate metaphors. The writers of the Bible record Jesus preaching to the multitudes using parables of invented figures and situations his audience could relate to. For thousands of years, preachers, teachers, parents, and anyone wanting to communicate clearly and effectively used the sugar of fiction to make the medicine of their message go down more easily.

Not only are human beings hard-wired for story, tales of the “untrue” actually bring us together. Stories are the connective tissue that allows us to travel outside the boundaries, not just of our homes and countries, but of our bodies and brains to exist in the mind of a character and view their world through their eyes. Fiction promotes critical thinking as well as empathy according to recent neuroscience research. The more emotionally transported a reader is by the content of the story, the stronger they are influenced by it. Narrative is a powerful agent of transformation, and these changes peel back the layers covering essential truths.

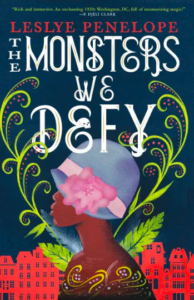

Consumer attitudes and corporate policies are shifted by a variety of factors, empathy being one of them. Popular culture and media influence people, change hearts and minds and, if you believe the arc of the universe bends towards justice, change the lives of everyday people. Whereas five years ago, I recall a popular Black author lamenting the fact that her White readers felt that a book with a Black character pictured on the cover wasn’t meant for them, today, it seems unthinkable that a publisher would want to “whitewash” a cover to make it more palatable for “mainstream” readers. That’s exactly what happened to Black science-fiction author Octavia Butler—a writer who has influenced just about every Black SFF author I know. The original cover of her novel Dawn featured a white representation of a Black character from the book (plus a white human representing a literal alien character).

And you don’t have to visit a previous century to find this happening. Portraying characters of color as white on book covers has been a not uncommon phenomenon affecting everyone from Ursula K. LeGuin to N.K. Jemisin. Thankfully, now when I walk down the science-fiction and fantasy aisle of my local bookstore, there are plenty of Black and brown faces gracing the covers. Less than a decade ago, such sights were extremely rare. A greater truth has taken hold, once that reassures readers of all races that every story can be one they will enjoy.

We’re uncovering what it means to be human and serving it back to our readers.On a technical level, fiction writers must contend with the difference between realism and verisimilitude, or the quality of appearing to be true. To me, this is the difference between truth and what comedian Stephen Colbert would term “truthiness.” Real life is true, whereas reality television, for example, is “truthy,” full of scripted conflicts and over-the-top shenanigans meant to entertain and display a heightened version of the participants’ lives.

When I began writing historical fiction—specifically historical fantasy—I struggled with exactly how true to history should I cling. My novel, The Monsters We Defy, takes a real person from the past, Clara Johnson, convicted in 1920 of killing a police detective who burst into her home, and fictionalizes her life. The purpose of the exercise was to use her story as a springboard to investigate the time, the community—Washington, DC—, the legacy of the Red Summer riots, and the resilience of Black Americans. The line between truthy and truth became blurred as I worked to make the setting come alive in an authentic way and also to maintain respect for the real person I was writing about, even as I sent her on a magical adventure she never took in reality.

The appearance of truth with the perceived distance of fiction allows a writer to delve into the heart of subjects in ways that journalism isn’t as well suited for. And within those depths, relatable emotional truths can be found. Scientists have shown that the human brain lights up the same way when someone reads about an activity as when they actually participate in it, so if we are all just ghosts inside of our material machines, then our experience of truth and so-called lies is virtually the same. If the emotions you feel when reading about an event are the same as you get when experiencing that event, it stands to reason that there is some kind of inescapable truth to be found in the stories we tell.

So I, for one, will not call myself a liar. As a writer, I believe I’m many things—a miner digging for gems of authenticity, a student of human psychology, an observer of natural phenomena, an inventor, counselor to my characters, chef, architect, interior decorator, programmer, the list goes on and on. The hats we wear are extensive and the skills we must wrangle and approximate can be perplexing. But it’s all in the pursuit of truth. We’re uncovering what it means to be human and serving it back to our readers.

___________________________________

The Monsters We Defy by Leslye Penelope is available now via Redhook.