Writing a Novel About a Half-Remembered Place, with the Help of Google Street View

Soon Wiley on Virtually Strolling the Streets of Seoul

When it comes to fiction, I can’t write about a place until I’ve left it. Over the years, I’ve found that I require some distance—sometimes psychic, sometimes literal—from my subject and the setting in which the story occurs. I’m a huge fan of what some writers like to call composting, wherein an author will allow long stretches of time to pass before they approach an experience, place, or memory, in their work. Like an actual compost pile, much of what happens during this process is invisible to the eye. Memories break down and degrade, but eventually, they provide the nutrients for the author’s imaginative powers.

It’s the complete opposite for a lot of writers, who like to strike while the iron’s hot, when their sensory details are at their most vivid and exacting. They can write about a place from the moment they inhabit it, snatching the essence of it and inserting it into their fiction. If I sound jealous of this process, it’s because I am. My memory isn’t the best, and while composting produces layered and textured fiction, it can be a slow and circuitous process.

Knowing this, one might assume I’m a meticulous note-taker or recorder. After all, what could possibly be more important to a writer trying to capture the essence of a place than first-hand observations and notes? When I first traveled abroad, with vague writerly aspirations, I was. Everywhere I went—London, Heidelberg, Salamanca—I carried with me a small black notebook and a pen, usually one of those Pilot Precise V5 pens that look very cool but are quite impractical as they tend to bleed everywhere.

Whenever I noticed something: the feel of cobblestones under my feet, the smell of ground espresso beans, a certain slant of late-afternoon light against a building, I would jot it down. Being the burgeoning, conscientious writer I was, I wanted to get the sense of place right in case I ever wanted to set a story there. I was fearful that if I didn’t get things down in writing, commit them to the page, I’d forget them, or worse, I might misremember something.

Memories break down and degrade, but eventually, they provide the nutrients for the author’s imaginative powers.A funny thing happened when I looked back at those notebooks years later. I was working on a short story set in Spain, and I was excited by the prospect of combing through all the various observations and anecdotes I’d written down during my time there. Much to my chagrin, though, almost nothing I’d written made any sense to me. The anecdotes were nonsensical; I couldn’t remember the context. The descriptions I’d written struck me as plain and forgettable. I couldn’t rely on my meticulous notes after all. Instead, I was forced to remember and imagine.

After that dispiriting experience I stopped writing things down all together, even when something struck me as creatively interesting. If I needed to recall something for a story—an ocean view, the taste of a particular dish—I planned to rely solely on my memory, faulty as it is, and my imagination. I knew I was going to get certain things wrong, but the more I wrote, the more I realized that when drafting a piece of fiction for the first time, sometimes it’s best to give yourself the permission to make mistakes. It’s easy to fall into the research trap, checking the veracity of nearly every detail in a novel with a quick Google search, but for me at least, that exactness doesn’t leave room for a story.

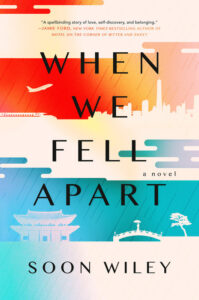

When I sat down to write what would become my debut novel, When We Fell Apart, I hadn’t set foot in Seoul, South Korea, where the novel takes place, for nearly five years. I’d initially moved to Seoul after graduating from college during The Great Recession. With few job prospects, I took a gig teaching English as a second language. At the time, I didn’t know I wanted to write a novel set in South Korea. I was busy applying to MFA programs for the following year and was primarily focused on writing short stories.

So, five years later, when it became clear that Seoul would serve as the setting for When We Fell Apart, I knew I had my work cut out for me. To make matters worse, it would end up taking me seven or so years to finish the novel, so by the time I submitted the final draft to my editors for approval, it had been over a decade since I’d lived in Seoul.

Working on early drafts of the novel, I gave myself permission to get it wrong. Street names, building facades, bus routes, and neighborhood aesthetics—I described them all as I remembered, resisting the urge to look through old photos or do a Google image search. In those early years, I was far more interested in capturing the mood of a nightclub, the vibe of a neighborhood, or the smell of a crowded subway car during rush hour. These qualities of setting are far more subjective and abstract; they also can’t be Googled.

Novels aren’t instruction manuals or travel guidebooks; they are a portal through which to see the world, and they work best when they play upon our senses. Vivid sensory details—rain on the wind, a river at dawn, the smell of freshly steamed rice, the whine of a motorbike weaving in and out of traffic—are what give readers access to a novel’s rich and layered fictional setting.

While I was working on draft after draft, I always told myself that if the novel was ever published—something that felt quite unlikely for the majority of the time I was writing it—I’d return to Seoul to make sure the setting resembled the city I’d conjured in my head. As much as I’d enjoyed imagining my characters walking around in the city, I owed it to my readers to make sure I’d captured the setting as accurately as possible. I didn’t want minor mistakes or incongruences pulling my readers from the fictional dream. If any of them were familiar with Seoul, my setting and descriptions needed to feel like a faithful interpretation of the city This trip would be about making sure I’d gotten subway stops, city blocks, and architectural details right. When I got the news that my novel was in fact going to be published, I immediately set about booking my trip. Then the pandemic hit.

Novels aren’t instruction manuals or travel guidebooks; they are a portal through which to see the world, and they work best when they play upon our senses.My travel plans to Seoul dashed, and the pandemic showing no signs of slowing down, I did what any writer, desperate to corroborate and authentic their own fictional account of a city would do: I turned to Google Maps. Starting at the beginning, I combed through my novel for moments that required more diligent research. My characters move around a lot. They take subways and buses; they traverse long city blocks. And I did the same, from my laptop.

I clicked on those cumbersome white squares, moving forward and back, sometimes smoothly, sometimes choppily, depending on my internet connection. Using “street view,” I was able to walk down the same streets as my characters, visit the same temples and palaces, and shop in the same high-end shopping districts. Where Google Maps proved most useful was in the details. Was that metro station above ground or subterranean? Was the façade of that bar really made of wood, or had I misremembered? Could my characters actually see Seoul Tower from where they were sitting? In this way, I took my trip to Seoul, and saw the city as my characters would have. I strolled through Namdaemun and Myeongdong market, peering into the stalls where my characters shopped. I meandered through tree-lined neighborhoods on the border of Bukhansan National Park, remembering when I’d walked there, some many years ago.

While doing my Google Maps “street view” research, I was consistently surprised at how well I’d recalled certain parts of Seoul in my novel. Even though I hadn’t been there in over a decade, the setting had somehow stuck into my consciousness. During my virtual walks around the city, I was also struck by how much Seoul had changed. There were office buildings and stores I didn’t recognize, housing developments that had seemed to rise from nothing. I don’t know if these changes were in fact changes at all, or if I’d simply forgotten or misremembered the city as it had always been.

To complicate matters, there was no way for me to timestamp the images I was looking at. Were these images representative of the city now? Or did this version of Seoul exist somewhere between when I’d lived there some twelve years ago and the present? That’s certainly one question that can’t be answered on Google. I’ll have to go to Seoul to get that answer.

As I’ve continued working on my second novel in earnest, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about whether I should change my approach and creative process. I sometimes wonder if I’d be a faster writer if I could write in the present moment, if I didn’t need to leave a place to capture it on the page, if I could simply visit a location and take notes. Then again, I suspect I’ll keep doing what I’ve always done because when you’re slipping into that deep imaginative space where you fully inhabit your characters, seeing what they see, feeling what they feel, well, there’s no greater moment for a writer.

_________________________________________________________

Soon Wiley’s novel When We Fell Apart is available now via Dutton.