What Pop Stars Can Teach Writers About Failure

On the Freedom of Doing Something New and Bad

If you’re interested in having a commercial hit as an author, you’re interested in being something akin to a pop star. Pop stars are artists who, by happenstance or design, make something lots of people like, then dedicate themselves to reproducing that success at the behest of their corporate benefactors. Many find this process suffocating, since they are dynamic human beings who seek new experiences and expressions as they change, while the market demands they replicate the same fun trick they did that one time on their hit record. Successful pop stars must keep making the same thing, slightly differently each time, but not unrecognizably differently, or they must do something difficult and rare: come up with a totally new trick that people like just as much as the first one.

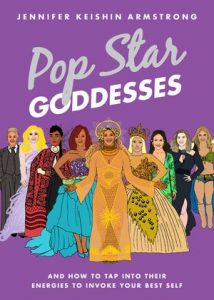

Commercially successful authors must do the same. I realized this as I researched and wrote my recent book Pop Star Goddesses, which charts the career and life trajectories of 35 female hit-makers of the last 30 years. We authors spend more time tending to flabby sentences than we do sculpting our bodies, and thank goodness for that. But we do tend to our public images—via social media and regular old media—with relatively equal obsession, performing the complicated choreography of balancing our personhood with our products.

I’ve experienced all of this over my ten years of writing books for major publishers. Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted was my passion project. I wrote a thorough proposal laying out the case for a history of The Mary Tyler Moore Show, emphasizing the many female writers—unusual for a 1970s comedy—who turned their own lives into storylines for the series. It went over well enough to sell at auction, and I ended up at Simon & Schuster. I cried with joy when I got the email from my agent.

The book was well-reviewed in major publications, including The New York Times, when it came out in 2013. If I were Adele, this would be my 19, not a breakthrough but good enough to advance to the next level. As a result, I got a second book with Simon & Schuster, though choosing the topic was tougher this time, with a committee involved. It was understood I would pick another TV show worthy of a cultural biography. But now, the show had to be bigger. Will & Grace was deemed too niche. A Cosby Show idea, conceived at a time when few were aware of the sexual assault allegations against Bill Cosby, thankfully died with the announcement of an impending Cosby biography. Finally, we settled on Seinfeld.

Stick around long enough and you’ll experience a downfall—in sales, in public affection, often in both. But a failure can be freeing.The result was a bestseller, making the New York Times list its first week and staying for many more. If I were Adele, this would be my 21, the one with “Rolling in the Deep” and “Someone Like You.”

Now, I had no choice for the next book.

I pitched new approaches to cultural criticism, working for the better part of a year on one proposal that I loved—and still love enough that I’m keeping it to myself. But that wasn’t what anyone wanted from me now, so it was time to pick another TV show. Could we find an even bigger one? We finally agreed on Sex and the City, which felt like a sure thing. There was a legitimate story to tell about women, sex, and consumerism on television in the 2000s. Everything Sex and the City seemed to turn to gold. Multiple massive-selling books had been Sex and the City-adjacent, from the Candace Bushnell collection that served as the basis for the TV series to the self-help guide He’s Just Not That Into You by Greg Behrendt and Liz Tucillo, which was based on just one line in the show.

From the day I signed that deal until the day the book came out in summer 2018, people inside the industry and out said the same thing to me: “This one is going to be bigger than the last one!” It made me nervous, but I also believed it. Aren’t careers supposed to go up, up, endlessly up?

What I learned is how expectations change everything. Sex and the City and Us actually did okay—better than Mary and Lou—but felt like a failure because it sold way less than Seinfeldia. When Seinfeldia made the bestseller list, I didn’t expect it at all. I didn’t even know when the list came out. I was in the back of a hired car on my way to a library event in New Jersey when I got a call from my agent with the news. On the Wednesday after Sex and the City and Us came out, I parked myself on the sofa with my laptop and refreshed my email constantly, waiting for the news that I had made the bestseller list, because that was what we all expected. I had wine ready to toast with. That email never came, that week or any other week. I had gone from bestseller back to midlist, and I felt the fall. If I were Lady Gaga, this would be my Artpop, the one everything seemed to be building up to, but instead was met with a shrug.

I began to understand why several authors have stopped publishing new, book-length works regularly after gigantic hits: Gillian Flynn after Gone Girl and Cheryl Strayed after Wild, for instance. Their peaks were so high, they were unmistakable, and they, perhaps, had the luxury of a nice long break as they waited for inspiration that’s truly worth the trouble and the risk.

After the crash, it’s tempting to keep up the pretense of world domination in the age of social media. I could not bring myself to correct people when they commented that I was “killing it!” or when they erroneously identified this book as a bestseller, too. I felt, once again, like a pop star, presenting the “bestselling author Barbie” version of myself on social media.

This is where my Pop Star Goddesses have taught me a lot. Writing about their long-term career arcs for the book showed me the patterns: Stick around long enough and you’ll experience a downfall—in sales, in public affection, often in both. But a failure can be freeing. Lady Gaga followed Artpop with Joanne, a departure into Americana and pink, wide-brimmed hats that no one asked for—but seemed to be invigorating to her. (And it is, for the record, my favorite Gaga album.) Britney Spears and Mariah Carey are also among the goddesses who have released excellent under-the-radar albums in recent years (Britney’s Glory in 2016 and Mariah’s Caution in 2018) while under far less immediate pressure to crank out hits.

And the best art often comes after you stop chasing hits. This is when you may—or may not—pull off the long-odds trick of doing something new that people like as much as, or more than, the trick you were known for before.

Some goddesses have done it. Beyoncé’s self-titled surprise release in 2013 marked a clear departure in her sound. She said it herself in the track “Haunted”: “I’m climbing up the walls ’cause all the shit I hear is boring / All the shit I do is boring / All these record labels boring.” And then: “Probably won’t make no money on this / Oh well.” Rihanna got similarly, beautifully weird and messy on her 2016 album ANTI. She hasn’t made one since, despite her fans’ constant histrionic pressure for more output. Both were critical smashes and did just fine on the charts, too.

Of course neither I, nor most working authors, can truly emulate Lady Gaga and Rihanna for one major reason: money. They might be risking their pristine record of hits, or even some bad reviews. But they’ve likely got a stash of money to get them through an album that sells only a few million instead of tens of millions, for instance.

At the same time, many of us do want to write hits, because we want to make our living as authors, or because we want to reach as many people as possible. That’s okay, too—another lesson I learned from my goddesses. Gwen Stefani, for instance, honestly recounted, in a New York Times interview, her devastation when her record executive told her to give up on hits and make “an artistic record” when she was 46. “Once you have a hit,” she said, “there’s not much point in ever writing a song that doesn’t have the intention of being a hit.”

Somewhere between here and Gwen Stefani lies a sweet spot, a place where we can balance love and money.I hope there always remains a point to writing a song, or a book, that will never be a hit. But I understand her position. I’m working on my next book now, more narrative nonfiction about TV history, but also a little different: When Women Invented Television will tell the stories of female pioneers in the medium from 1949 to 1955, who laid the foundation for what we watch today but have been largely forgotten. I hope it’s my Lemonade, but I’ll take a Joanne.

A few years ago, I started playing covers of my favorite pop songs at open mics, and I began frequenting a dance class where we learn the real choreography to Britney and Beyoncé songs. I am in no danger of someone sullying these efforts by offering to pay me for them, so they have reminded me of what it felt like when I first started writing, when no one was waiting for me to produce anything, much less expecting me to reach a certain very large number of people with my work.

Somewhere between here and Gwen Stefani lies a sweet spot, a place where we can balance love and money. The money part may get harder in the years to come, as the world and its economy attempt to find normal after the coronavirus pandemic and publishing figures out its place in it. But we can look to our favorite pop stars for that bit of inspiration to begin, to feel like a superhero version of ourselves as we put on our Joanne hat and start writing those lyrics. Maybe we’ll pull a Beyoncé and sell the world on a whole new trick of ours. If not, remember that even Lady Gaga has her down moments.

__________________________________

Pop Star Goddesses by Jennifer Keishin Armstrong is available now via Morrow Gift.