The Annotated Nightstand: What K-Ming Chang Is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Leslie Marmon Silko, Norman Erikson Pasaribu, Agustina Bazterrica, and More

In K-Ming Chang’s Organ Meats, two girls, Anita Hsia and Rainie Tsai, live in a drought-ridden unnamed town in the United States. Anita has a boundless imagination that connects with the otherworldly. Rainie is more staid, rational—or, perhaps, inclined to give into the dull life society provides. They are linked by red threads they both wear around their necks so they can be collared dogs.

This allows them to connect to the neighborhood strays that lounge near a sycamore. Anita’s mother once told her human women used to be dogs. “Men want a dog,” she explains as the reason. “They want someone who will need them, you know, who will never refuse them….Dogs will take anything you give them.”

Ultimately Anita and (eventually) Rainie work to turn these expectations on their head, instead providing loyalty only to the deserving. They access dog-women elders throughout and largely gain wisdom and guidance. This is alongside some distressing ideas about girlhood and womanhood. “Don’t forget: A tree without fruit is only good for firewood,” Chang writes. “A daughter who doesn’t bear children must burn.” At another instance: “girls should have ears but not mouths if they wanted to survive.”

Fantastical and chaotic, it’s hard to tell what’s real, dream, or the girls’ invention in Organ Meats—or if those delineations even matter. Chang employs a variety of forms and povs: dialogue, letters, from Anita’s perspective, an omniscient—but also the mythical dogs/women elders that oversee the girls. Recurring images throughout include: pearls, trees, hair, dogs, red thread, bones. Family stories, myths, experiences, and invention circle each. Violence is often at the heart of these tales. “Our scars are a map back to each other,” Anita tells Rainie.

When Rainie goes unconscious for two weeks after she’s bitten by a dog and one of its teeth is embedded in her wrist, Anita marks her forehead to ensure she can find her. Their queer love of one another and wild appraisal of the world around them is something Anita is confident in while still a child—but Rainie often finds herself resisting both. Rainie’s family moves when they’re ten. Soon after, Anita disappears from her body in a dreamscape where she learns of her origins, entering what Rainie might call a coma.

Ten years later, Rainie returns. “The distance between their bodies felt planetary,” Rainie realizes as she looks at her friend whose body has begun to disintegrate with the help of ants and mushrooms. “[Rainie had] once been Anita’s accomplice, corroborating her truths and lies, wearing the same collar of red, but now their histories had splintered.” Thus begins Rainie’s journey to enter Anita’s approach to the world—of dreams, imagination, and the dog guides they turned to as children.

Men are (blessedly) rare in this book. When any fathers pass through, they’re barely present. Brothers are allowed to exist, but sometimes they are killed by their sisters via women ghosts stuck in trees. At one point, Anita’s cousin Vivian gets pregnant from someone they call “Mr. McDonald’s” (where he and Vivian go to hook up in his car). After Anita’s mother and Vivian go steal the vehicle, Vivian gives birth to a girl, expanding their cadre of women. “Men are digressions,” Vivian says at one point, and the book’s plot certainly illustrates that feeling.

This points to the most exciting thing about this novel to me—how sparingly yet compellingly Chang demonstrates that a world where patriarchy and the ordinary thrive is an obvious affront to life. After she returns, Rainie meditates on how Anita’s absence from her body reminded Rainie of something she has also felt. “When her mother spoke to her about marriage,” writes Chang, “Rainie could see the outline of her life but without her body inside it.”

The prose in Organ Meats is knockout—but what makes the novel revolutionary is that within its pages two girls are allowed to transform their lives through mischief and devotion. In its glowing starred review, Publishers Weekly states, “Chang’s hallucinogenic prose is wild and alive, a savage yawp of liberating beastliness in the face of all that would seek to yoke her heroes to the dreary laws of man.”

Chang tells us about her pile, “My to-read pile is like a north star for my writing life—I love navigating my way toward themes, language, and brilliant writers whose work inspires me and who I want to be in conversation with. I especially love reading fiction in translation and how they expand the possibilities of language on the page. I owe so much to queer novels in translation, and I’m constantly feeling regenerated and invigorated and awakened by them. I try to let myself be guided by instinct and joy when I choose what to read next, rather than making strategic plans. This helps make it feel like play and pleasure rather than reading as work, which can sometimes happen. I find that whenever reading no longer feels like a refuge, rereading favorites and revisiting influential childhood books always returns me to that sense of giddy excitement and urgency.”

*

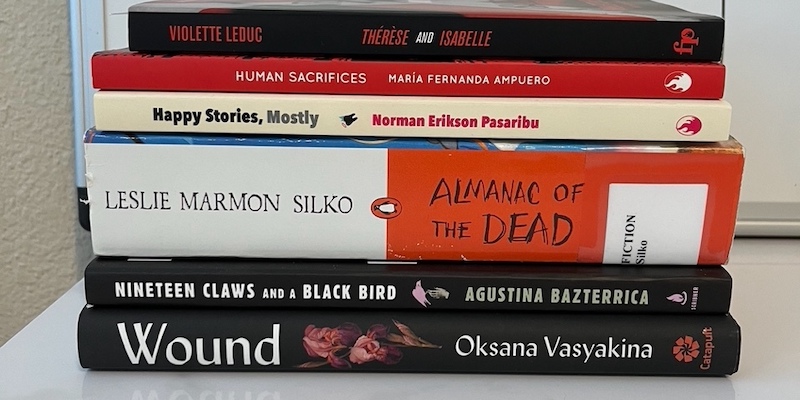

Violette Leduc, Thérèse and Isabelle (tr. Sophie Lewis)

An excerpt of this 1968 novella is in Asymptote, which includes a translator’s note from Sophie Lewis. Lewis writes, “Thérèse and Isabelle has been multiply blocked, suppressed, and censored, ostensibly due to its sexual content. Its story is simple: the account of a passionate relationship between teenage girls in a convent school during one school term. And it’s true I found it hard work translating the sex. The English don’t have many options between the poles of smut and surgery. I began intending to match Leduc’s aim to describe everything precisely, including “the flower, the meat of a woman’s open sex,” but found that sometimes, so as not to draw more attention to that meat than Leduc had intended, I could only take refuge in saying, rather than her sex or her vagina or her labia, more simply and yet evasively, her.” Lewis goes on an quotes Leduc: “I am trying to render as accurately as possible, as minutely as possible, the sensations experienced in physical love….I am not aiming for scandal but only to describe the woman’s experience with precision.”

María Fernanda Ampuero, Human Sacrifices (tr. Frances Riddle)

A recently published collection of short stories from the Ecuadorian author Ampuero describes by Kirkus as “Terrifying stories lay bare the brutality of patriarchy and the violence it metes out on women and children.” The review goes on: A sense of claustrophobia dwells in these pages. A few stories in, the reader begins to prepare for the horrible thing (or things) that will inevitably happen. Page after page, women and children are brutalized and raped. Confronted by one monstrous scene after another, the reader becomes almost inured to the collection’s representations of violence. The stories are strongest when they avoid relying on the shock value of human cruelty and experiment with the possibilities afforded by the form of the short story.

Norman Erikson Pasaribu, Happy Stories, Mostly (tr. Tiffany Tsao)

Happy Stories, Mostly was longlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize. The Booker committee writes of the book, “Powerful blend of science fiction, absurdism and alternative-historical realism that aims to destabilize the heteronormative world and expose its underlying rot….Inspired by Simone Weil’s concept of “decreation” and drawing on Batak and Christian cultural elements, in Happy Stories, Mostly Pasaribu puts queer characters in situations and plots conventionally filled by hetero characters. In one story, a staff member is introduced to their new workplace—a department of Heaven devoted to archiving unanswered prayers. In another, a woman’s attempt to vacation in Vietnam after her gay son commits suicide turns into a nightmarish failed escape. And in a speculative-historical third, a young man finds himself haunted by the tale of a giant living in colonial-era Sumatra.

Leslie Marmon Silko, Almanac of the Dead

I quoted from Lou Cornum’s essay about Almanac of the Dead when the book was on Myriam Gurba’s TBR pile (and I recommend people do give that a read!). It’s funny, now, to read the hatchet job PW attempted on this enduring and totemic work: “there are virtually no decent nor likable characters here; even those of indigenous American descent have been corrupted by modern culture and ancient hate. Despite its laudable aims, this meandering blend of mystical folklore, thriller-type violence and futuristic prophecy is unwieldy, unconvincing and largely unappealing.” Luckily readers have an enduring interest in unlikeable and indecent characters (no matter their identity markers), as well as “unwieldy” narratives that combust the usual tropes. As Cornum notes, “In 1991, a book like Almanac had never been produced in Native American literature, and nothing like it has been produced since. Many mainstream critics struggled with how to relate to it.”

Agustina Bazterrica, Nineteen Claws and a Black Bird (tr. Sarah Moses)

In her New York Times review of Bazterrica’s short story collection, Kate Folk quotes the book from the start: “She was horrified by the traces of monstrosity in everyday life.” Folk goes on that this “could be read as a unifying principle for all twenty stories.” Folk states of Nineteen Claws and Black Bird, Moses’ translation from the Spanish captures the playful gruesomeness of the Argentine writer’s prose. Misogyny and its knock-on effects are an animating force throughout….Endings come with a twist as characters sanguinely accept their fates, as if to concede they should have seen it coming. Bazterrica takes big swings throughout, and while not every punch lands, these stories are fresh and unnerving.

Oksana Vasyakina, Wound (trans. Elina Alter)

Wound was one of the most anticipated books of the year for Electric Lit, where Michelle Hard writes, Late last year, ten months after the invasion of Ukraine, the Russian government passed a law banning open expressions of LGBTQ identity, which they deemed “propaganda.” The voices of queer Russians are necessary now more than ever, to be broadcast loud and proud, so it feels particularly special to have this moving and wonderfully witty work of autofiction about a lesbian poet traveling from Moscow to her hometown in Siberia to inter her mother’s ashes.

______________________________

Organ Meats by K-Ming Chang is available via One World.