The Annotated Nightstand: What Henry Hoke is Reading Now and Next

Featuring Catherine Lacey, Jan Morris, and Amina Cain

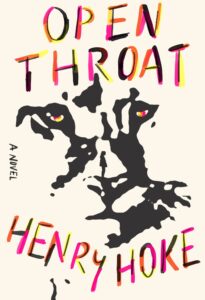

Henry Hoke’s newest book—a novel entitled Open Throat—begins “I’ve never eaten a person but today I might.” It’s only when we get a few pages in that we realize the speaker isn’t human but a mountain lion in the drought-ravaged Los Angeles basin. “I need water to come from the sky or anywhere else // I need more than a dirty sip,” he says after watching two hikers glug from water bottles and talk about “scarcity mentality.” “I’m not sure what a scare city mentality is // but I have it.”

For the uninitiated, the speaker is undoubtedly cougar P-22, a local celebrity the LA Times reported on dozens of times. P-22 crossed two freeways to reach Griffith Park from the Santa Monica Mountains, the sole puma in the central LA area. Sadly, P-22 was injured by a car and eventually captured and euthanized just this last December. His memorial brought thousands of people to commemorate his life, which for years had helped stoke interest and funding for a wide variety of programs for local wildlife.

As the New York Times put it, “[P-22’s] story of isolation—he was a bachelor who never mated—and survival in a city that has a tendency to grind down individuals… resonated with Angelenos.” Or, as Hoke’s speaker puts it, “I’m not from ellay I just ended up here.”

So we have the star of Hoke’s book—a novel that messes with the conventions of prose to attend to what a mountain lion might think or pay attention to. Punctuation doesn’t exist, space is rampant. He fantasizes about eating a man and successfully eats bats, coyotes, caterpillars. Mostly his sleep is interrupted by often-vapid conversations between hikers about earthquakes, work, relationships, and therapy.

These conversations are Hoke’s ways to throw into relief the ways in which humans manage to ignore the crises (drought) and wonders (mountain lion) around them. “I’m a good listener says the man and I see he’s with a woman who hikes beside him… it’s just this specific stuff with us that makes us hard.” The narrator listens on for a paragraph-long speech from the man, then states, “I don’t hear the woman’s voice and I start to wonder what she sounds like // I wonder what I sound like.”

The voicelessness of a creature growing increasingly desperate for water, food, darkness, and quiet are the focus of Hoke’s work here, while wryly illustrating the absurdity of that which humans devote their attention. As the Kirkus Review states, “Hoke’s prose is a joy, as it alternatingly charms with malapropisms… and stuns with poetic simplicity.”

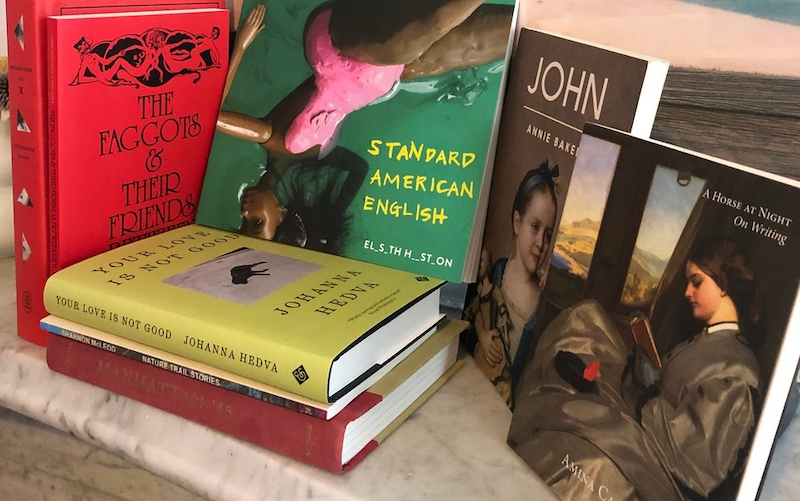

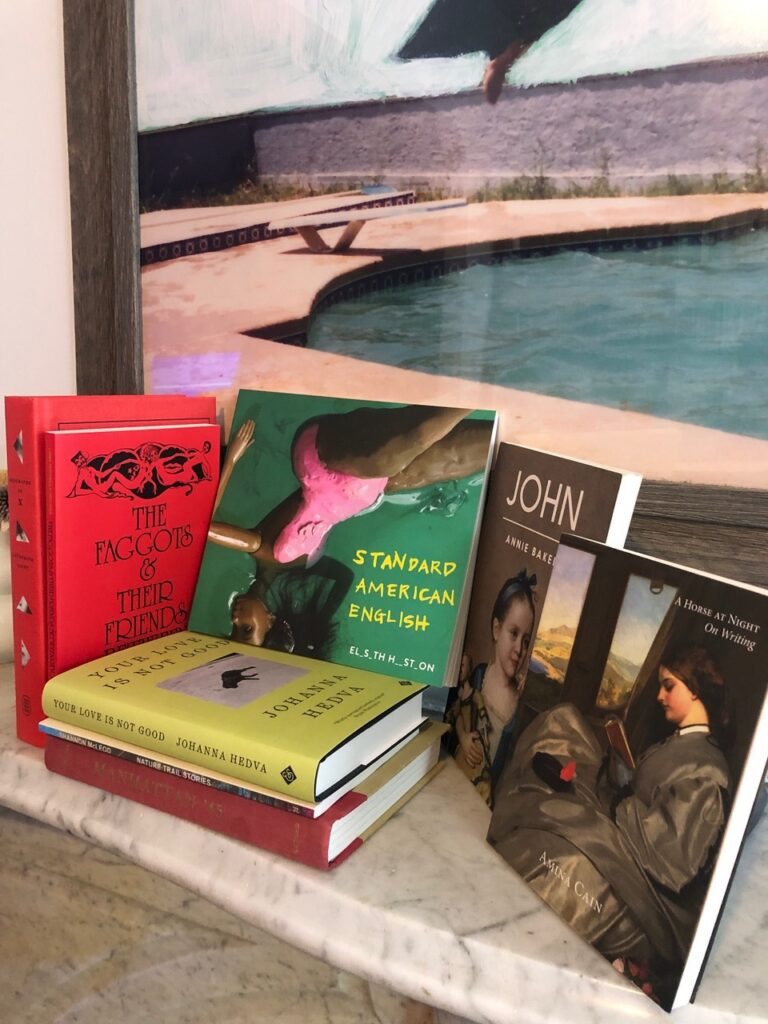

Regarding his to-read pile Hoke tells us, “As publication of Open Throat nears, I’m starting to assemble another novel. I like to surround myself with books that don’t explicitly intersect with my work-in-progress. These are my current companions, and I’m excited for their illuminations of language, art, and uniquely American pain.”

Catherine Lacey, Biography of X

A book we’ve been seeing everywhere, and for good reason. Biography of X was named a “most anticipated book” by BuzzFeed, Chicago Review of Books, Electric Lit, Esquire, The Guardian, LitHub, Time, and the New York Times. The titular character is an artist who dies, leaving her grieving wife with the desire to chronicle X’s life.

As the jacket copy states, “Though X was recognized as a crucial creative force of her era, she kept a tight grip on her life story. Not even CM knows where X was born, and in her quest to find out, she opens a Pandora’s box of secrets, betrayals, and destruction. All the while, she immerses herself in the history of the Southern Territory, a fascist theocracy that split from the rest of the country after World War II, and which finally, in the present day, is being forced into an uneasy reunification.”

Larry Mitchell, The Faggots & Their Friends Between Revolutions

This iconic 1977 book, with illustrations from Ned Asta, was republished by Nightboat to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. Mitchell intended to write a children’s book as a reaction to the gay literature of the time, yet it ultimately ended up as this novel. Artforum describes it as “a fantastical, libidinous fairytale-cum-manifesto that takes place in the land of Ramrod under the leadership of Warren-And-His-Fuckpole, where faggots and their friends (namely, women) live and love and lie in waiting for the next revolution against the culture of men.”

Amazingly, the book was given a life as a musical in 2017. Performer Morgan Bassichis handed the book to audience members to have them read aloud with intermittent musical performances from actors. “Do you think this is going to be the next Hamilton?” he asked. Everyone responded, “Yes!”

Elisabeth Houston, Standard American English

I hosted Houston on an earlier post for this column where I wrote of her first collection: I first encountered the poet and interdisciplinary artist Elisabeth Houston’s work the way she generally prefers one does: through her performances. In each, Houston assumed the persona of Baby. She had tape over her mouth and wrote a series of questions for the audience on blank pages.

Many years ago, I watched her write WHO HERE IS RACIST? on a page. Her eyes scanned as everyone sat, silent, with their hands down—myself included. NO ONE????? she wrote. These engagements pointed to issues of racism, society, and our own complicity so directly (shouldn’t we all have raised our hands?), I was haunted by them for days. When Houston-as-Baby removed the tape and did speak, it was stilted, slow, and deep.

Houston read aloud poems that often described the cruelties the character Baby endured in this otherworldly tone. Her poetry about Baby hung on the walls for us to read, which were from third person or Baby’s perspective. They scrutinized situations regarding trauma, feminism, class, racism, Blackness, sexuality, family, and so much more in powerful verse.

Johanna Hedva, Your Love Is Not Good

Also out this month, Hedva’s novel follows a queer mixed-race white-Korean-American artist who struggles to find her footing both in her identity in society and the art world. As the Kirkus Review of the book explains,

“After a period of relative stasis in her career, the narrator has two important solo shows lined up but finds herself without inspiration. Her search for a muse leads to Hanne, an LA art-world siren who initially attracts her with the proud, heedless power of her beauty and quickly becomes the focal point not only for the narrator’s art, but also for the dynamic conflict between the narrator’s own ideas about Whiteness—how it is ‘hard to paint precisely because it’s everywhere and in everything… It’s the image of the world. And yet no one can see it for itself because there’s no such thing as an ipseity of white…’—and desire, where it comes from and who controls both its expression and its repercussions.”

Shannon McLeod, Nature Trail Stories

McLeod’s collection of stories was published earlier this year. I appreciated how, considering the title, the trailer was essentially a slow walk on a hiking trail with trippy music, then a pan over a muddy river before the blurbs came on the screen. In short, it’s a mood. Ursula Villarreal-Moura writes of the book,

“In Nature Trail Stories, Shannon McLeod’s characters tenderly negotiate their private lives and their public lives with others and in nature. She depicts responsible, helpful citizens doing their best within the dynamics of family, friendships, and community. Nature is more than simply a setting in this book—it is a character that offers possibility. Nature Trail Stories is bursting with heart and well-crafted sentences. McLeod’s sharp observations make for clever, enjoyable reading that will make you chuckle. The book ends beautifully with ‘Easier to Convince,’ a page-turning novella about youth, choices, and self-discovery. Readers familiar with her previous book Whimsy will fall in love with her mastery of the novella form all over again.”

Jan Morris, Manhattan ’45

In the 1987 New York Times review of this book, Roger Starr explains that Manhattan ’45 “gives the reader a short but incisive course on the difficulty of writing history…One can sense Ms. Morris’s gropings for the texture of a reality she can read about but not directly feel. One vital aspect of it she understands profoundly: that in 1945 New York stood at a pinnacle of collective strength that resembled at their peak the power of Venice, Alexandria or Byzantium—all seaports too.

Not quite so accurately perceived is that the collective consciousness of power did not overcome individual feelings of weakness at the immense unknown future ahead.” Starr goes on in ways that feel simultaneously true and absurd: “The city has declined from its state in 1945, though one element of its power, money, has continued to grow. But Ms. Morris makes clear that visual indexes of living power—shipping and smoke, trucks laden with cargoes for Europe, new and mighty bridges and airfields—have dwindled in importance.”

Annie Baker, John

I love any excuse to quote Hilton Als. In 2015 he reviewed the off-Broadway production of the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright’s John for the New Yorker. Als writes, “While most new plays run for two hours or less—about the length of a TV movie—Baker’s fourth full-length original script clocks in at three hours and fifteen minutes, the running time of, say, a short, late-career Eugene O’Neill drama.

By not rushing things—by letting the characters develop as gradually and inevitably as rain or snowfall—Baker returns us to the naturalistic but soulful theatre that many of her contemporaries and near-contemporaries have disavowed in their rush to be ‘postmodern.’ With ‘John,’ Baker has done something exceptional on a political level, too: she has declared her ambition. The truth is that it’s still an anomaly for women artists to claim this kind of space for themselves and their work.”

Amina Cain, A Horse at Night: On Writing

One of my most beloved outcomes of doing this column is learning about books I might have missed—both recently published and deep in the historical library shelves. I love Cain’s work and, likely because of my own failings, didn’t realize this had come out. Sophie Brown reviewed A Horse at Night in Astra (remember that glorious magazine that left us far too soon?). Brown writes,

“Slender and essayistic, A Horse at Night roams through the literature and visual art in Cain’s subconscious, from the words of Virginia Woolf, Rachel Cusk and Toni Morrison to filmmakers including Chantal Akerman and David Lynch. Fragments of moving image, performance art, paintings, etchings, and prints materialize and dissipate, and a dialogue between these impressions opens up like a portal of ambiences, coming into focus yet remaining out of grasp.

‘In my own fiction, I sometimes find myself trying to conjure something that isn’t there, so that it both is and isn’t appearing,’ she writes. This is also true of her nonfiction. In some ways this book functions as a gallery of interiority, deep and fluctuating with nebular dispositions and impulses. It is an effort towards articulating the intangible. A Horse at Night is a transmutation of fiction and nonfiction, a form of unfurling, soft and grainy at the edges. Moving through this text feels like resting your eyes on shifting shapes on a walk in the dusk.”

____________________

Henry Hoke’s Open Throat is available now from MCD.