There are hundreds of thousands of kids’ books out there. Some are classics that wind up in everyone’s homes, no matter what. Others are random—given as gifts, found on the playground, purchased in bulk from the resale shop. But which books are worth your child’s time—and (arguably) more importantly, your time?

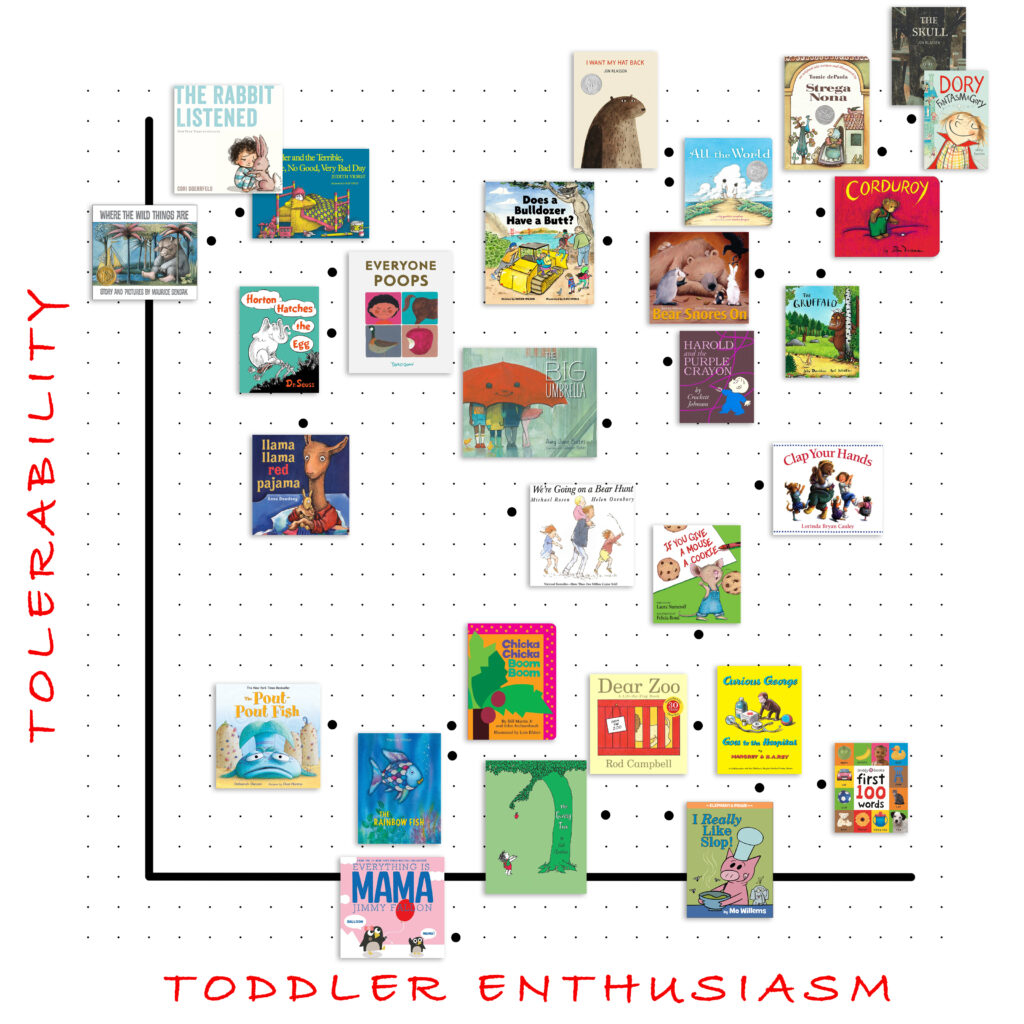

Overwhelmed by the number of both brilliant and mediocre books I have read since becoming a parent, I asked other Lit Hub staff members with toddlers to rank a few of their most memorable reading experiences on two metrics: their child’s enthusiasm for it and their own enthusiasm for it—or let’s be real and say, their tolerance for reading it over and over and over again. The result is the graph below.

Obviously, these rankings are highly subjective, and reliant on a number of shifting factors, including exact age and mood of toddler, interests of parent, and the number of times the book in question has been read in any given week/day/hour. This is also not an exhaustive list of all the books we read to our children, or that they like, or that we like, etc. To be quite honest, the graph could have been 20 times as large, but bedtime is coming.

Click on the graph to enlarge it; you will also find a list of the books on the graph, organized by descending total score, along with comments from various Lit Hub staff members, given on the condition of anonymity (to protect the feelings of gift-givers and other interested parties).

And of course, if you are someone who loves books and also a toddler-aged child or three, feel free to rank some books of your own in the comments.

The Results:

Abby Hanlon, Dory Fantasmagory – 25 tolerability x 25 toddler enthusiasm = 50 points

All the Dory Fantasmagory books are beloved by parents and child alike in our house. Bonus points for the audiobooks being free on Spotify now.

Jon Klassen, The Skull – 25 x 25 = 50

We all love it.

Tomie dePaola, Strega Nona – 24 x 24 = 48

Everyone can recite it by memory at this point, which helps with eye strain.

Don Freeman, Corduroy – 21 x 22 = 43

The Lisa obsession is real.

Julia Donaldson, The Gruffalo – 20 x 22 = 42

Julia Donaldson in general is great; The Gruffalo is the best and the kids love it.

Jon Klassen, I Want My Hat Back – 24 x 17 = 41

Murder bear.

Karma Wilson, Jane Chapman, Bear Snores On – 20 x 20 = 40

A classic.

Liz Garton Scanlon, Marla Frazee, All the World – 23 x 17 = 40

Makes Mom all teary.

Derick Wilder, K-Fai Steele, Does a Bulldozer Have a Butt? – 21 x 15 = 36

Who is more immature, me or my child?

Crockett Johnson, Harold and the Purple Crayon – 17 x 17 = 34

Always a solid pick.

Lorinda Bryan Cauley, Clap Your Hands – 14 x 20 = 34

There’s something slightly deranged about this book, but I don’t hate it.

Amy June Bates and Juniper Bates, The Big Umbrella – 15 x 15 = 30

This book is nice and we all like it.

Roger Priddy, First 100 Words – 4 x 22 = 26

For…some reason…my child thinks this is called “Boring Book.” She loves Boring Book.

Dr. Seuss, Horton Hatches the Egg – 20 x 6 = 26

Great but the kids hated it.

Laura Joffe, Numeroff, Felicia Bond, If You Give a Mouse a Cookie – 8 x 18 = 26

I hated it.

Judith Viorst, Ray Cruz, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day – 22 x 3 = 25

Couldn’t get my kids to care about it, unfortunately.

Cori Doerrfeld, The Rabbit Listened – 22 x 3 = 25

A beautiful book. Kids hated it but it’ll make you cry.

Tarō Gomi, Everyone Poops – 18 x 6 = 24

Will it really help with potty training? Who knows, but I laugh at the camel poop every time.

Michael Rosen, Helen Oxenbury, We’re Going on a Bear Hunt – 12 x 12 = 24

It’s fine.

Maurice Sendak, Where the Wild Things Are – 21 x 2 = 23

I love Sendak, but my 2-year-old won’t tolerate this for more than a few pages. Maybe she’ll grow into it.

Margaret and H.A. Rey, Curious George Goes to the Hospital – 3 x 20 = 23

Our lack of enthusiasm due to it not having been updated since the 50s, so all the nurses are women and all the doctors are men.

Rod Campbell, Dear Zoo – 5 x 18 = 23

Kids love it, but it makes no sense. That’s not how zoos work.

Anna Dewdney, Llama Llama Red Pajama – 15 x 5 = 20

Another one we wanted her to like more than she did. There’s still time!

Mo Willems, the Elephant and Piggie books – 2 x 17 = 19

Two unpleasantly-drawn creatures on a white page, bellowing at each other about nothing.

Shel Silverstein, The Giving Tree – 2 x 15 = 17

Maybe it was meant as an allegory for humankind’s relationship with the planet, but it reads queasily like the American expectation for parenthood, and I am not a fan. (Luckily, someone has fixed it.)

Bill Martin Jr., John Archambault, Lois Ehlert, Chicka Chicka Boom Boom – 5 x 10 = 15

Parenthood is trying enough, and now you want me to convincingly declare “skit skat skoodle doot, flip flop flee”?

Marcus Pfister, The Rainbow Fish – 4 x 10 = 14

Teaching children that the way to make friends is to give away all the things about you that are unique.

Deborah Diesen, Dan Hanna, The Pout-Pout Fish – 5 x 6 = 11

Teaching children that all their problems/shitty personalities will be solved if they can only attract sexual attention from a stranger.

Jimmy Fallon, Everything is Mama – -2 x 10 = 8

Nakedly capitalist.

]]>On Sunday, the Danish monarch, Queen Margrethe, abdicated her throne after 52 years (which makes her the longest-reigning monarch in Danish history), in favor of her son, Frederik X.

Monday was the new king’s first formal day on the job (he visited Parliament), but it wasn’t until today, his third day as king, that he got around to publishing a book. What restraint! It’s called Kongeord (The King’s Word) and according to the BBC it “promises Frederik’s thoughts on topics including Denmark’s place in the world and his relationship with his wife, Queen Mary.”

On the latter subject, the book includes this bit: “I have learned a lot from having a wife who, from time to time, reminds me that of course I am not always right, and that my words are not automatically believed, just because I am a man in the house.” Well…good.

The book, which runs about 110 pages, was written with Jens Andersen, who published a 2017 biography of Frederik’s 2017 biography, and is reportedly based on interviews conducted over the last eighteen months.

]]>It’s safe to say that we were awash in adaptations of The Great Gatsby even before the copyright expired at the end of 2020—from opera to ballet to stage to film to video games to radio, not to mention television and er, film. But since then, the re-envisionings (or at least the announcements thereof) have come in a deluge, as we are, shall we say, borne back ceaselessly into the past, with a prequel, a graphic novel, an animated feature, a “diverse, inclusive” miniseries, a fanfic written by a college class (and then optioned for film), a Florence Welch musical, and also a totally different musical, which producers have announced is coming to Broadway this spring, starring Jeremy Jordan as Gatsby and Eva Noblezada as Daisy.

“The lavish production will join a spring Broadway season packed with new musicals at a moment when many industry leaders are concerned that there do not seem to be enough patrons to keep most of the shows afloat,” writes Michael Paulson in The New York Times. But the show, which premiered at the Paper Mill Playhouse last fall, was the highest grossing show in the venue’s history. Which at least suggests that—despite widespread grumbling about our current state of global IP purgatory and my strong personal feeling that the answer to the question posed by this headline is no, after all the novel is unfortunately perfect and you almost certainly have a copy in your house already—people are still interested in new versions of Fitzgerald’s classic American story. Maybe it will . . . save Broadway?

So we beat on, etc.

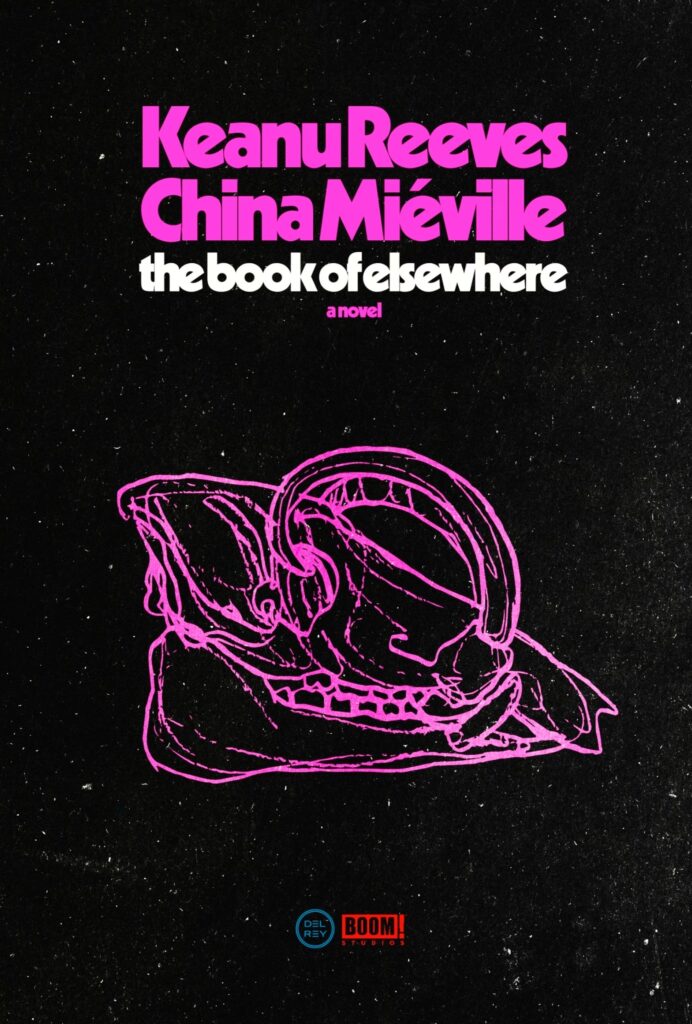

]]>Yep—noted art book publisher, comic book writer, and all-purpose hero Keanu Reeves is back to bless the darkest timeline with a novel. The Book of Elsewhere, which will be published by Del Rey on July 23, 2024, was co-written with China Miéville, and is set in the world of the BRZRKR comics that Reeves wrote with Matt Kindt and artist Ron Garney. According to the publisher, the novel “follows an immortal warrior on a millennias-long quest to discover the key to his immortality—and perhaps, a way to free himself from it.”

“It was extraordinary to have the opportunity to collaborate on The Book of Elsewhere with one of my favorite authors, China Miéville,” said Keanu Reeves in a press release. “China did exactly what I was hoping for—he came in with a clear architecture for the story and how he wanted to play with the world of BRZRKR, a world that I love so much. I was thrilled with his vision and feel honored to be a part of this collaborative process.”

“Sometimes the greatest games are those you play with other people’s toys,” China Miéville said. “It was an honour, a shock and a delight when Keanu invited me to play. But I could never have predicted how generous he’d be with toys he’s spent so long creating, how glad to experiment together, how open to true collaboration. I hope readers get to experience even a fraction of the pleasure reading The Book of Elsewhere that I experienced in the writing—in the serious business of play.”

Here’s the cover:

Happy 2024—may it be better than 2023 2022 2021 2020 you expect. To that end, here are a selection of literary films and tv shows hitting screens large and small in the year to come. Might as well entertain ourselves while the world burns. (NB that premiere dates are subject to change, and plenty haven’t been announced yet, especially in the second half of the year.)

January

Fool Me Once

January 1, Netflix

Literary bona fides: based on Fool Me Once by Harlan Coben (2016)

You can always count on Harlan Coben for a twisty mystery—in this one, a woman is shocked when she sees a mysterious man on her nanny cam, not least because the man is her husband, who was murdered two weeks previously. Or so she thought… Daniel Brocklehurst’s eight-part limited series adaptation transports the events of the novel to the UK and stars Michelle Keegan, Adeel Akhtar, Joanna Lumley and Richard Armitage. Early reviews are mixed, but apparently fans are digging it.

Society of the Snow

January 4, Netflix

Literary bona fides: based on Pablo Vierci’s Society of the Snow: The Definitive Account of the World’s Greatest Survival Story (2009)

In 1972, a Uruguayan Air Force flight carrying 45 passengers and crew, including 19 members of the Old Christians Club rugby union team, crashed in the Andes. 72 days later, 16 survivors were rescued. Journalist Pablo Vierci, who knew many of the players, interviewed all of the survivors for his book, which he says seeks to chronicle not just the grueling facts but “what happened in the minds and hearts” out there in the snow; the film too focuses on the emotional story, to great effect.

The Bricklayer

January 5, Vertical Entertainment

Literary bona fides: based on The Bricklayer (2010) by Noah Boyd (Paul Lindsay)

The latest from Renny Harlin (Die Hard 2) looks as formulaic as can be: an ex-CIA operative hauled out of retirement for One Last Job, a sexy location, a sexier handler, an international conspiracy, Aaron Eckhart. But appetite for action thrillers is apparently bottomless, and maybe it will be good?

He Went That Way

January 5, Vertical Entertainment

Literary bona fides: based on Conrad Hilberry’s Luke Karamazov (1987)

It sounds interesting—an animal trainer (Zachary Quinto) transporting a once-famous-but-now-down-on-his-luck monkey named Spanky picks up a teenage hitchhiker (Jacob Elordi) who turns out to be a serial killer. Road trip with a monkey, a serial killer, and Old New Spock? I’m listening… but unfortunately, early reviews aren’t great.

Monsieur Spade

January 14, AMC

Literary bona fides: based on Dashiell Hammett’s beloved character

In this neo-noir series from Scott Frank (The Queen’s Gambit) and Tom Fontana (Oz), a certain detective you may have heard of called Sam Spade (Clive Owen) has retired to the South of France. But detectives you’ve heard of aren’t allowed to retire! New murders and old adversaries conspire to ruin (or enhance?) Spade’s golden years, as of course they must, and plenty of intrigue ensues.

Death and Other Details

January 16, Hulu

Literary bona fides: inspired by Agatha Christie, and also every literary detective ever

All right, it’s not an adaptation, but don’t you want to see Mandy Patinkin as a details-obsessed detective in a “post-fact” present, stuck on a lavish ocean liner? I do—especially because writers and executive producers Mike Weiss and Heidi Cole McAdams are big Agatha Christie fans. “We love Agatha Christie novels,” they told EW. “We’ve read everything she’s ever written. We wanted to capture the atmosphere of those works and drag her style into our contemporary world.” Fun.

The End We Start From

January 19, Paramount

Literary bona fides: based on Megan Hunter’s The End We Start From (2017)

This adaptation of Hunter’s poetic debut novel, adapted by Alice Birch (Normal People) and directed by Mahalia Belo, stars Jodie Comer as the central mother character, who flees a flooded London with her infant, along with Katherine Waterston, Benedict Cumberbatch, Mark Stron, and Joel Fry. Here’s hoping it will do the book, which isn’t an obvious candidate for adaptation, despite the fact that Cumberbatch’s production company acquired the rights before it was published, justice. Early signs are good.

Origin

January 19, Neon

Literary bona fides: inspired by—and about—Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of our Discontents (2020)

Ava DuVernay takes an unusual, ambitious approach to Isabel Wilkerson’s bestselling nonfiction book, which frames American racism as part of an unacknowledged caste system in this country. “The film is not so much an adaptation of Caste but an attempt to translate it into the vernacular of narrative cinema,” wrote Bilge Ebiri in a review for Vulture. “To do this, DuVernay goes back to basics: She presents Wilkerson herself (played by Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor) as the protagonist of this drama and portrays the author’s very personal journey as she’s pulled into this subject, even as her life is falling apart. But she also rifles through history to present case studies from Wilkerson’s research—sometimes through extended sequences, sometimes through mere flashes. The results are incredibly ambitious and, frankly, devastating.” Interestingly, despite the fact that DuVernay’s screenplay for Origin was classified as original by the Writers Guild of America, it will be considered an adapted screenplay for Oscars consideration—the same judgement the Academy made for Barbie.

Which Brings Me To You

January 19, Decal

Literary bona fides: based on Steve Almond and Julianna Baggott’s Which Brings Me to You (2005)

Two people meet at a wedding, and sparks fly. Unfortunately, both of them (Lucy Hale as Jane, freelance writer, and Nat Wolff as Will, photographer) are pretty terrible at relationships. The book this movie is based on is an epistolary love affair, as the two spill their guts through written letters; the film crams all the confessing into a 24-hour spree. Could be a sort of fun meta rom-com, or could be a romantic burnout—we’ll have to see.

The Peasants

January 26, Next Film

Literary bona fides: based on Władysław Reymont’s The Peasants (1909)

If you saw the experimental Van Gogh biopic Loving Vincent (2017), which was the very first fully painted feature film, you’ll probably be pleased to learn that directors and writers DK Welchman and Hugh Welchman are back with another movie that uses the same animation technique—this one based on Polish writer Wladyslaw Reymont’s, novel, originally published in installments between 1904 and 1909. Reymont won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1924, with the Academy specifically citing The Peasants as “his great national epic.” Early reviews are mixed, but if nothing else, the film looks beautiful.

Expats

January 26, Amazon Prime Video

Literary bona fides: based on Janice Y.K. Lee’s The Expatriates (2016)

When, one wonders, will directors stop torturing Nicole Kidman? In this six-part series, created by Lulu Wang (The Farewell), Kidman plays Margaret, a wealthy American expat living in Hong Kong, whose young son disappears on a crowded street, paralyzing her with guilt and grief. Newcomer Ji-young Yoo plays Mercy, the young woman who is blamed for the disappearance, and Sarayu Blue plays Margaret’s friend and neighbor, who is contending with her inability to have children at all. As the parent of a toddler, I will absolutely not be watching this, but early buzz is good.

Feud: Capote vs. the Swans

January 31, Hulu

Literary bona fides: based on Laurence Leamer’s Capote’s Women: A True Story of Love, Betrayal, and a Swan Song for an Era (2021)

For the second season of his Feud series, Ryan Murphy takes on a legendary piece of literary gossip—the time Truman Capote backstabbed all his fancy, hard-won, high-society lady friends (whom he of course called his “swans”) by publishing a thinly veiled short story, “La Côte Basque 1965”—an excerpt from his then-unpublished novel Answered Prayers—in Esquire, revealing a few too many of their secrets. Capote then found himself, to his shock, resoundingly excommunicated, and neither he nor his career ever really recovered (though his legacy is fine). Tom Hollander plays Capote, and Calista Flockhart, Diane Lane, Naomi Watts, and Chloë Sevigny star along with Demi Moore, Molly Ringwald, and Ella Beatty. This looks faintly ridiculous, in the best way.

February

Argylle

February 2, Universal Pictures/Apple Original Films

Literary bona fides: Probably not an adaptation, definitely about a novelist

The latest addition to the micro-genre of movies about writers whose books come true (are there many more than Stranger Than Fiction and Ruby Sparks?) is this goofy, deranged-looking spy action comedy, directed and produced by Matthew Vaughn (Stardust, Kick-Ass, the Kingsman movies) and written by Jason Fuchs (Wonder Woman). Perhaps you remember the minor media mystery over Elly Conway, who was listed as the unknown author of the debut book this big-budget “adaptation” was based on? Ha, ha, it was all a publicity hoax, it seems, because it turns out that Elly Conway is the writer in the movie, whose unpublished spy novel-in-progress begins to come true, making her the target of lots of guns and killing. And the movie is real, you see? This might have worked better if more people cared about the identity of writers…but perhaps that is the whole point of this film? Head-exploding emoji, as the kids would never say.

The Promised Land

February 2, Magnolia Pictures

Literary bona fides: based on Ida Jessen’s The Captain and Ann Barbara (2020)

Mads Mikkelsen makes anything good—so if you’re in the market for an epic historical drama about the common man vs. the aristocracy vs nature vs. chaos vs. good vs. evil, this adaptation of Ida Jessen’s Danish best-seller is a pretty good bet.

The Tiger’s Apprentice

February 2, Paramount+

Literary bona fides: based on The Tiger’s Apprentice by Laurence Yep (2003)

This animated adaptation of the first book in Yep’s The Tiger’s Apprentice trilogy has been delayed for literal years, but will finally be released to streaming in February. In it, Chinese-American teenager Tom Lee, who’s minding his own business in San Francisco until he discovers he’s connected to a group of magical protectors called the Guardians—and they need him. Of course. For kids or kids at heart.

One Day

February 8, Netflix

Literary bona fides: based on David Nicholls’ One Day (2009)

Ambika Mod and Leo Woodall star in this limited series adaptation of David Nicholls’ bestselling novel (in which two people meet every day, on the same day, for 20 years, cue the swoonage), the book’s second chance at a screen life after the disappointing 2011 feature film.

Nancy Rivera/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images

Nancy Rivera/Bauer-Griffin/GC Images

It Ends With Us

February 9, Sony Pictures

Literary bona fides: based on Colleen Hoover’s It Ends With Us (2016)

The behemoth of all CoHo behemoths was optioned in 2019, even before its BookTok-fueled resurgence—the final product, directed by and starring Justin Baldoni along with Blake Lively, from a screenplay by Christy Hall, will be in theaters just in time for Valentine’s Day. It will almost certainly make money.

Lisa Frankenstein

February 9, Focus Features

Literary bona fides: very very loosely based on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818)

Look, the idea of Frankenstein (say it with me: Frankenstein is the doctor) has firmly transcended Mary Shelley’s novel at this point, so whether we can really count this as a “literary film” is arguable. But mad scientist or no, this is my list, and I mean, teen goth resurrects Victorian hottie in a tanning bed, and then murders ensue—as written by Diablo Cody? My deep nostalgic love for the age of Heathers and Weird Science demands that I’ll give it a whirl.

Drift

February 9, Utopia

Literary bona fides: based on Alexander Maksik’s A Marker to Measure Drift (2013)

Directed by Anthony Chen from a screenplay by Susanne Farrell and Alexander Maksik, Drift stars Cynthia Erivo as a young Iberian refugee who lands on a Greek island, where she meets and bonds with American tour guide Alia Shawkat while she tries to move on from her past. Early reviews are mixed, but Erivo is always worth watching.

Shōgun

February 27, Hulu

Literary bona fides: based on James Clavell’s Shōgun (1975)

Clavell’s epic bestseller, itself loosely based on the true story of William Adams, one of the first Englishmen to reach Japan, has already been adapted into a beloved (or at least constantly shown on TV) 1980 miniseries. FX’s new adaptation looks pretty spectacular, though, starring Hiroyuki Sanada as Lord Toranaga, Cosmo Jarvis as Adams-stand-in John Blackthorne, and Anna Sawai as the translator/samurai Toda Mariko.

March

Spaceman

March 1, Netflix

Literary bona fides: based on Jaroslav Kalfař’s Spaceman of Bohemia (2017)

Adam Sandler is Jakub Procházka, a Czech astronaut sent on a dangerous mission, leaving his wife (Carey Mulligan) behind. Paul Dano plays the giant talking space spider, and for those who have not read the novel, that is all I will say about that. I’m always glad to see Sandler in a role like this; I have high hopes for this movie.

Dune: Part Two

March 1, Warner Bros. Pictures and Legendary Picture

Literary bona fides: based on Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965)

The long-awaited follow-up to Dune: Part One—let’s be honest, you already know whether you’re going to see it. (Florence Pugh and Christopher Walken are in this one!)

Manhunt

March 15, Apple TV+

Literary bona fides: based on James L. Swanson’s Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer (2006)

Monica Beletsky’s historical thriller, based on Swanson’s bestselling and Edgar Award-winning nonfiction book, follows Edwin Stanton in the days after Lincoln’s assassination, as John Wilkes Booth leads him on a “wild, 12-day chase” across the country. Starring Tobias Menzies as Stanton and Anthony Boyle as John Wilkes Booth.

Palm Royale

March 20, Apple TV+

Literary bona fides: based on Juliet McDaniel’s Mr. & Mrs. American Pie (2018)

In 1969, striver Maxine Simmons (Kristen Wiig) tries with all her might to make it into Palm Beach’s “high society.” Fun. The costumes already have my attention, and so does the cast: Wiig is joined by Ricky Martin, Josh Lucas, Leslie Bibb, Amber Chardae Robinson, Mindy Cohn, Julia Duffy, Kaia Gerber, with Laura Dern, Allison Janney and “extra special guest stars” Bruce Dern and Carol Burnett. Whew.

3 Body Problem

March 21, Netflix

Literary bona fides: based on Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem (2008)

David Benioff and D.B. Weiss (Game of Thrones) are back, bringing in Alexander Woo to adapt Chinese novelist Liu Cixin’s beloved apocalyptic science fiction epic, which even Obama loved. “The scope of it was immense,” he said. “So that was fun to read, partly because my day-to-day problems with Congress seem fairly petty—not something to worry about. Aliens are about to invade!” Hopefully this series will bring us the same level of escape as we stare down the maw of 2024.

Arthur the King

March 22, Lionsgate

Literary bona fides: based on Mikael Lindnord’s Arthur: The Dog Who Crossed the Jungle to Find a Home (2016)

Mark Wahlberg, making friends with a dog, and then bringing him along on a 435-mile race in the Dominican Republic. Ah sure, why not?

One Life

March 22, Warner Bros. Pictures

Literary bona fides: Barbara Winton, If It’s Not Impossible…The Life of Sir Nicholas Winton (2014)

Anthony Hopkins stars in this heartfelt biopic about Nicholas Winton, a British stockbroker who helped hundreds of Jewish children escape German-occupied Czechoslovakia in the months leading up to WWII—and who, decades later, got to meet some of those children on the BBC television show That’s Life.

Mickey 17

March 29, Warner Bros. Pictures

Literary bona fides: based on Edward Ashton’s Mickey7 (2022)

In the latest film from the brilliant and terrifying Bong Joon-ho’s new film, in which Robert Pattinson plays an “expendable” worker on a space mission to colonize an ice planet—expendable because of technology that can regenerate his body if anything goes wrong. Steven Yeun, Naomi Ackie, Toni Collette, and Mark Ruffalo also star, and according to the WGA credits, Charles Yu contributed “additional literary material” for the film. Highest hopes for this.

Lousy Carter

March 29, Magnolia Pictures

Literary bona fides: a terrible, horrible, no good, very bad lit prof movie

I will simply paste the logline for this movie, which stars David Krumholtz, Martin Starr, and Olivia Thirlby, here: “Man-baby Lousy Carter struggles to complete his animated Nabokov adaptation, teaches a graduate seminar on The Great Gatsby, and sleeps with his best friend’s wife. He has six months to live.” Seems painful—but maybe in a good way.

Wicked Little Letters

March 29, Sony Pictures Classics

Literary bona fides: it’s about the power of (swear) words, gang

This is another film that I will be counting as literary: a black comedy starring Olivia Colman and Jessie Buckley (based on an actual scandal in 1920s England), in which a slew of mysterious, obscene, and insulting letters begin arriving in the postboxes of all the fine, upstanding citizens of a small town. Obviously, the first move is to blame the least conforming woman in town—because if she isn’t doing it, who is?

NBCU

NBCU

Apples Never Fall

March, Peacock

Literary bona fides: based on Liane Moriarty’s Apples Never Fall (2021)

A mystery miniseries about secrets—aren’t they all? But if you’re wondering what to expect, Liane Moriarty wrote the book that Big Little Lies was based on (also called Big Little Lies)—that should be elevated by a star-studded cast, which includes Annette Bening, Sam Neill, Alison Brie, and Jake Lacy.

And Beyond:

Civil War

April 26, A24

Literary bona fides: written and directed by Alex Garland

Obviously, by now Alex Garland is more of a filmmaker than he is a novelist, but he’s still a literary one. This speculative action film (A24 doing action!) follows a group of reporters helmed by Kirsten Dunst as they try to cover, and survive, an all-consuming American Civil War. Looks terrifying, to be fair.

The Idea of You

May 2, Amazon Prime Video

Literary bona fides: based on Robinne Lee’s The Idea of You (2017)

Michael Showalter directs and Gabrielle Union produces this adaptation of the novel written by actress Robinne Lee, in which a 40-year-old divorcée (Anne Hathaway) takes her daughter to Coachella and winds up falling for the famous lead singer of a boy band (Nicholas Galitzine), who was inspired by—you guessed it—Harry Styles. Why not, I ask you?

Horrorscope

May 10, Sony Pictures

Literary bona fides: based on Nicholas Adams’s Horrorscope (1992)

In which a group of friends have their horoscopes read and then begin dying—in ways related to their fortunes. (Gotta love a 90s horror premise.)

The Watchers

June 7

Literary bona fides: based on A.M. Shine’s The Watchers (2021)

Ishana Night Shyamalan—the daughter of a certain director—makes her feature directorial debut with The Watchers, in which a young artist (Dakota Fanning) finds herself lost in the Irish wilderness. Then she finds what seems like shelter—but is actually something more like a cage, presided over by the mysterious creatures who rule the forest.

Cold Storage

June 20

Literary bona fides: based on David Koepp’s Cold Storage (2019)

Obviously, David Koepp, who is most famous as a screenwriter—ever heard of Jurassic Park or Mission: Impossible?—wrote the screenplay for this feature adaptation of his 2019 biohazard thriller. The film is produced by Gavin Polone (Curb Your Enthusiasm) and stars Liam Neeson and Joe Keery; whatever the result, the writing should be top-notch.

The Bikeriders

June 21

Literary bona fides: based on The Bikeriders by Danny Lyon (1967)

Delayed half a year due to the SAG-AFTRA strike, Jeff Nichols’ latest film is based on an iconic photo-book by influential documentary photographer Danny Lyon, who embedded with the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club from 1963-1967 and emerged with incredible photographs and stories. The film, which tracks the club’s transformation over a decade, stars Jodie Comer, along with Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, Michael Shannon, Mike Faist, and Norman Reedus.

Firebrand

June 21

Literary bona fides: based on Elizabeth Fremantle’s Queen’s Gambit (2013)

Divorced, beheaded, she died; divorced, beheaded, survived—this film, directed by Brazilian director Karim Aïnouz from a screenplay by Henrietta Ashworth and Jessica Ashworth, tells the (revisionist) story of the only queen to make it through being married to Henry VIII—Katherine Parr, played by Alicia Vikander. Jude Law plays the king (Henry wishes).

Harold and the Purple Crayon

August 2, Sony Pictures

Literary bona fides: based on Crockett Johnson’s Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955)

The still-mysterious live-action adaptation of what feels like a pretty unadaptable book has been pushed back twice, and will now supposedly hit theaters this summer. It stars Zachary Levi, Lil Rel Howery, and Zooey Deschanel, and was directed by Carlos Saldanha.

The Wild Robot

September 20, DreamWorks

Literary bona fides: based on Peter Brown’s The Wild Robot (2016)

Based on Peter Brown’s bestselling middle-grade novel, the film follows a robot—designed for an urban world—that gets shipwrecked on an island and must adapt to the landscape and ingratiate itself to the wildlife. Will it be the new WALL-E?

White Bird

October 4, Lionsgate

Literary bona fides: based on R.J. Palacio’s White Bird (2019)

In October, Wonder fans will be treated to a spin-off based on 2019 graphic novel of the same name by R.J. Palacio. This is another film that has been massively delayed—it was originally scheduled for fall 2022.

The Amateur

November 8, 20th Century Studios

Literary bona fides: based on Robert Littell’s The Amateur (1981)

Rami Malek stars as Charles Heller, a CIA cryptographer whose wife is killed in a terrorist attack—and like all good spy thriller heroes, decides he must take matters into his own hands to avenge her. Rachel Brosnahan, Caitríona Balfe, Laurence Fishburne, and Adrian Martinez also star.

The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim

December 13, Warner Bros.

Literary bona fides: based on a story from the appendices of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings

The LOTR universe goes anime. I have mixed feelings about the infinite adaptation possibilities Tolkien left us, but I do not have mixed feelings about Brian Cox, who stars in this installment as the voice of Helm Hammerhand.

Also anticipated and expected—but unconfirmed—for 2023:

The Sympathizer

TBD, HBO Max

Literary bona fides: based on Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer (2015)

This limited series based on Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel is “an espionage thriller and cross-culture satire” that stars Hoa Xuande as the Captain, a biracial mole and spy during the Vietnam War who becomes an exile in the US. Park Chan-wook and Don McKellar co-showrun and executive produce, along with Robert Downey Jr., who apparently plays more than one role. Can’t come quickly enough, really.

A Gentleman in Moscow

TBD, Showtime

Literary bona fides: based on Amor Towles’s A Gentleman in Moscow (2016)

Showtime’s series adaptation of Towles’s big bestseller stars Ewan McGregor as Count Alexander Rostov who, after the Russian Revolution, is sentenced to house arrest in a hotel attic by a Bolshevik tribunal—but discovers a rich world within.

Janet Planet

TBD, A24

Literary bona fides: written and directed by Annie Baker

Anything from Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Annie Baker is worth a look; her feature directorial debut, which stars Julianne Nicholson, Zoe Ziegler, Elias Koteas, Sophie Okonedo, and Will Patton, focuses on the interior life of an 11-year-old who is just beginning to free herself from her mother’s orbit.

Turtles All the Way Down

TBD, HBO Max

Literary bona fides: based on John Green’s Turtles All the Way Down (2017)

The film adaptation of Green’s bestselling YA novel about a teenager with OCD is directed by Hannah Marks from a screenplay by Elizabeth Berger and Isaac Aptaker, and stars Isabela Merced.

Trust

TBD, HBO Max

Literary bona fides: based on Hernan Diaz’s Trust (2022)

This may or may not actually make it to screens in 2024, given that Kate Winslet, who stars, also headlines another HBO original limited series, The Regime, which airs in March (that show gets an honorary place on this list, because Gary Shteyngart is one of the writers). Perhaps they’ll want to spread out the Kate, but we can hope.

The Spiderwick Chronicles

TBD, Roku

Literary bona fides: based on Tony DiTerlizzi and Holly Black’s The Spiderwick Chronicles (2003-2009)

Fans of the children’s fantasy series will be pleased to learn that Roku picked up this eight episode series after it was dropped in 2023 by Disney+; it is slated to air in early 2024.

The Shrinking of Treehorn

TBD, Netflix

Literary bona fides: based on Florence Parry Heide’s The Shrinking of Treehorn (1971)

How will Ron Howard adapt this wonderful, weird little book, originally illustrated by Edward Gorey, about a child who mysteriously begins to shrink (much to the disinterest of his parents)? I don’t know, but I’m looking forward to finding out.

Lady in the Lake

TBD, Apple TV+

Literary bona fides: based on Laura Lippman’s Lady in the Lake (2019)

Lippman’s bestselling psychological noir, set in 1960s Baltimore and based on two real-life murders from the era, has been given the miniseries treatment by Alma Har’el (Honey Boy), and stars Natalie Portman and Moses Ingram.

Dark Matter

TBD, Apple TV+

Literary bona fides: based on Blake Crouch’s Dark Matter (2016)

Joel Edgerton stars in Crouch’s series adaptation of his novel, about Jason, a physicist who winds up in a parallel universe created by a choice he made 15 years before—the choice not to marry his wife Daniela (Jennifer Connelly). Turns out there are many Jasons, and they are angry. Should be fun!

The Legacy of Mark Rothko

TBD

Literary bona fides: Lee Seldes’s The Legacy Of Mark Rothko (1974)

Russell Crowe plays legendary abstract expressionist Mark Rothko in this film, directed by by Sam Taylor-Johnson, which focuses on the battle over his estate after his suicide.

]]>Another year has come and gone, full of best books—and also bestsellers. As it turns out, just 23 percent of the bestselling books of 2023 were actually published in 2023—which is only a slightly smaller share than last year. Backlist books typically dominate the overall bestseller list, thanks to sales of oft-assigned, always-popular classics and beloved children’s books (Sandra Boynton and Eric Carle 4ever), as well as those spurred by film adaptations or other major cultural events.

Just like last year, Colleen Hoover dominated the overall bestseller list in 2023—but mostly for her backlist books, since she only (only) published three new books in 2023, as compiled by Publishers Lunch. (Publishers Lunch counts a 17 books by Hoover in the overall top 200, which is, ahem, 8.5 percent.) Sarah J. Maas had 6 titles on the overall list, Ana Huang and Dav Pilkey had 5 each, and Emily Henry had 4. Hey, people know what they like!

So without any further ado, here are the bestselling books of 2023 that were published in 2023, per Publishers Lunch. (NB: the number in parentheses is the book’s place on the overall list of bestsellers.) There isn’t anything overly surprising here, but it’s fun to see that, unlike last year, a work of literary fiction made the list: Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water, which also happens to be one of only two books on the below list to also appear on our compendium of the critics’ favorite books of the year. (The other one is Britney’s, of course.)

The list:

1. (3.) Prince Harry the Duke of Sussex, Spare (Random House, Jan. 10)

2. (4.) Rebecca Yarros, Fourth Wing (Red Tower, May 2)

3. (6.) Dav Pilkey, Dog Man: Twenty Thousand Fleas Under the Sea: A Graphic Novel (Dog Man #11) (Graphix, Mar. 28)

4. (8.) Rebecca Yarros, Iron Flame (Red Tower, Nov. 7)

5. (10.) Britney Spears, The Woman In Me (Gallery, Oct. 24)

6. (13.) Hannah Grace, Icebreaker (Atria, Feb. 27)

7. (15.) Jeff Kinney, No Brainer (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 18) (Abrams, Oct. 24)

8. (21.) Wendy Loggia, Taylor Swift: A Little Golden Book Biography (Golden Books, May 2)

9. (23.) Emily Henry, Happy Place (Berkley, Apr. 25)

10. (26.) Colleen Hoover, Heart Bones (Atria, Jan. 31)

11. (29.) Colleen Hoover and Tarryn Fisher, Never Never (Canary Street , Feb. 28)

12. (31.) Colleen Hoover, Too Late: Definitive Edition (Grand Central, Jun. 27)

13. (34.) Rick Rubin, The Creative Act: A Way of Being (Penguin Press, Jan. 17)

14. (38.) Peter Attia, Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity (Harmony, Mar. 28)

15. (39.) David Grann, The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder (Doubleday, Apr. 18)

16. (41.) John Grisham, The Exchange: After the Firm (Doubleday, Oct. 17)

17. (46.) Stephen King, Holly (Scribner, Sep. 5)

18. (52.) Lucy Score, Things We Hide from the Light, (Bloom, Feb. 21)

19. (54.) Abraham Verghese, The Covenant of Water, (Grove, May 2)

20.(60.) Rick Riordan, Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Chalice of the Gods (Hyperion, Sep. 26)

The end of the year is approaching, the universe is expanding, and the internet is updating—right now, it is mostly updating its Best Of lists. Therefore, per Literary Hub tradition, I will now present to you the Ultimate List, otherwise known as the List of Lists—in which I read all the Best Of lists and count which books are recommended most.

This year, I sorted through 62 lists from 48 publications, which yielded a total of 1,132 books. (I can only say: yikes.) 94 of those books made it onto 5 or more lists, and I have collated these for you here, in descending order of frequency.

*

20 lists:

James McBride, The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store

19 lists:

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Chain-Gang All-Stars

David Grann, The Wager

Zadie Smith, The Fraud

16 lists:

Jonathan Eig, King: A Life

15 lists:

Eleanor Catton, Birnam Wood

R.F. Kuang, Yellowface

Rebecca Makkai, I Have Some Questions For You

Ann Patchett, Tom Lake

Safiya Sinclair, How to Say Babylon

Jesmyn Ward, Let Us Descend

14 lists:

Mariana Enriquez, tr. Megan McDowell, Our Share of Night

Paul Murray, The Bee Sting

13 lists:

S.A. Cosby, All the Sinners Bleed

Naomi Klein, Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World

Catherine Lacey, Biography of X

12 lists:

Claire Dederer, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma

Deepti Kapoor, Age of Vice

Victor LaValle, Lone Women

11 lists:

Emma Cline, The Guest

Daniel Mason, North Woods

Justin Torres, Blackouts

Abraham Verghese, The Covenant of Water

Colson Whitehead, Crook Manifesto

10 lists:

Matthew Desmond, Poverty, By America

Lauren Groff, The Vaster Wilds

Kelly Link, White Cat, Black Dog: Stories

Jonathan Rosen, The Best Minds: A Story of Friendship, Madness, and the Tragedy of Good Intentions

C Pam Zhang, Land of Milk and Honey

9 lists:

Darrin Bell, The Talk

Timothy Egan, A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them

Alice McDermott, Absolution

Ann Napolitano, Hello Beautiful

John Valliant, Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World

8 lists:

Jen Beagin, Big Swiss

Jamel Brinkley, Witness

Nicole Chung, A Living Remedy: A Memoir

Anne Enright, The Wren, The Wren

Jenny Erpenbeck, tr. Michael Hofmann, Kairos

Tania James, Loot

Jessica Knoll, Bright Young Women

Hilary Leichter, Terrace Story

Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes

Maggie Smith, You Could Make This Place Beautiful

Héctor Tobar, Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino”

Ilyon Woo, Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey from Slavery to Freedom

7 lists:

Daniel Clowes, Monica

Michael Finkel, The Art Thief: A True Story of Love, Crime, and a Dangerous Obsession

Homer, tr. Emily Wilson, The Iliad

Benjamin Labatut, The MANIAC

Dennis Lehane, Small Mercies

Elliot Page, Pageboy: A Memoir

6 lists:

Sebastian Barry, Old God’s Time

Gary J. Bass, Judgment at Tokyo: World War II on Trial and the Making of Modern Asia

Ned Blackhawk, The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History

Tania Branigan, Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution

Tananarive Due, The Reformatory

Teju Cole, Tremor

Tessa Hadley, After the Funeral and Other Stories

Isabella Hammad, Enter Ghost

Rachel Heng, The Great Reclamation

Tahir Hamut Izgil, Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet’s Memoir of China’s Genocide

Angie Kim, Happiness Falls

Deborah Levy, August Blue

Yiyun Li, Wednesday’s Child: Stories

Lorrie Moore, I Am Homeless If This is Not My Home

Donovan X. Ramsey, When Crack Was King: A People’s History of a Misunderstood Era

Britney Spears, The Woman in Me

Barbra Streisand, My Name is Barbra

Alice Winn, In Memoriam

Yepoka Yeebo, Anansi’s Gold: The Man Who Looted the West, Outfoxed Washington, and Swindled the World

5 lists:

Naomi Alderman, The Future

Anne Berest, tr. Tina Kover, The Postcard

Cat Bohannon, Eve: How the Female Body Drove 200 Million Years of Human Evolution

Tom Crewe, The New Life

Patricia Engel, The Faraway World

Patricia Evangelista, Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in My Country

Anna Funder, Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life

Cristina Rivera Garza, Liliana’s Invincible Summer: A Sister’s Search for Justice

Paul Harding, This Other Eden

Mick Herron, The Secret Hours

Nathan Hill, Wellness

Lydia Kiesling, Mobility

Jhumpa Lahiri, tr. Jhumpa Lahiri and Todd Portnowitz, Roman Stories

Andrew Leland, The Country of the Blind: A Memoir at the End of Sight

Ayana Mathis, The Unsettled

Marie NDiaye, tr. Jordan Stump, Vengeance Is Mine

Mark O’Connell, A Thread of Violence: A Story of Truth, Invention, and Murder

Caroline O’Donoghue, The Rachel Incident

Ed Park, Same Bed Different Dreams

Salman Rushdie, Victory City

Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki, Roaming

Brandon Taylor, The Late Americans

Paul Yoon, The Hive and the Honey

List of Lists Surveyed:

The New Yorker’s The Best Books of 2023 (The Essentials) • The New York Times’s 100 Notable Books of 2023 and 10 Best Books of 2023 • TIME’s The 100 Must-Read Books of 2023 • The Atlantic’s The Books That Made Us Think the Most This Year • Publishers Weekly’s Best Books 2023 • The Wall Street Journal’s The 10 Best Books of 2023 • The Los Angeles Times’s 13 Best Novels (And 2 Best Short Story Collections) of 2023 • The Washington Post‘s 50 Notable Works of Fiction and 50 Notable Works of Nonfiction and 10 Best Books of 2023 • Vulture’s The Best Books of 2023 • Slate’s The 10 Best Books of 2023 (Laura Miller) and The 10 Best Books of 2023 (Dan Kois) • Electric Literature’s Best Novels of 2023, Best Nonfiction of 2023, and Best Short Story Collections of 2023 • The Economist’s Best Books of 2023 • Vanity Fair’s 20 Favorite Books of 2023 • Esquire’s The 20 Best Books of 2023 • Oprah Daily’s The Best Books of 2023 • Den of Geek’s Best Books of 2023 • Amazon’s Top 20 Books of the Year • Book Riot’s Best Books of 2023 • Chicago Tribune’s 10 Best Books for 2023 • Inside Hook’s The 10 Best Books of 2023 • The Guardian’s Best Books of 2023 • Powell’s Books’ Best Books of 2023: Fiction and Best Books of 2023: Nonfiction • Real Simple’s 60 Best Books of 2023 • Good Housekeeping’s The Must-Read Books of 2023 • AIR MAIL’s 12 Best Books of 2023 • The New York Public Library’s Best Books for Adults 2023 • The Boston Globe’s 55 Books We Loved in 2023 • Book Soup’s Best Books of 2023 • The Chicago Review of Books’ Best Books We Read in 2023 • The California Review of Books’ 10 Best Books of 2023 • The Globe and Mail’s The Globe 100: The Best Books of 2023 • Tattered Cover’s Books of the Year 2023 • ELLE’s Editors Share the Books They Loved Best in 2023 • The New Statesman’s 20 Best Books of 2023 • Harper’s Bazaar’s The 45 Best New Books of 2023 You Won’t Put Down • The Chicago Public Library’s Favorite Books of 2023 and Top 10 Books of 2023 • BookPage’s Best Fiction of 2023 and Best Nonfiction of 2023 and Best Mystery & Suspense of 2023 and Best Romance of 2023 and Best SFF & Horror of 2023 and 10 Best Books of 2023 • Shelf Awareness’s Best Adult Books of 2023 • Kirkus Reviews’ Best Fiction Books of the Year and Best Nonfiction Books of the Year • Library Journal’s Best Books 2023 • The Telegraph’s 50 Best Books of 2023 • The Conversation’s Best Books of 2023 • The New York Post’s Best Books of 2023 • PEOPLE’s Top 10 Books of 2023 • Foreign Affairs’ The Best of Books 2023 • Town & Country’s The Best Books of 2023 • The Independent’s 25 Best Books of the Year • and of course, Literary Hub’s The 38 Best Books We Read in 2023.

]]>And yet again, we’ve reached the end of a long, bad year. For the sake of posterity, and probably because we’re masochists, here’s the second installment of the 50 biggest literary stories of 2023, so you can remember the good, the bad, and all the literary cool girls we met along the way. Have fun:

30.

The End of an Era for the Old Guard of Publishing

One of the many knock-on effects of Penguin Random House’s failed attempt to acquire Simon & Schuster was the acceleration of departures by a legendary generation of editors, the final act in an era of publishing upheaval that began with the COVID pandemic and Black Lives Matters protests of 2020.

Gone now are the likes of Daniel Halpern (founder of Ecco Press), Victoria Wilson (who worked with Anne Rice and Lorrie Moore), Ann Close (editor of Lawrence Wright, Alice Munro, and Norman Rush), Shelley Wanger (Edward Said, John Richardson, Joan Didion), Jonathan Segal (seven of his books have won Pulitzers), Kathy Hourigan (who worked closely with Robert Caro for decades), Wendy Wolf (Nathaniel Philbrick, John Barry, and Steven Pinker), Rick Kot (Barbra Streisand, Andrew Ross Sorkin, and Ray Kurzweil), and Paul Slovak (Amor Towles, Elizabeth Gilbert, and David Byrne).

Most of these editors and publishers took generous buyout packages from a company eager to trim its expenses. And as this expansive New York Magazine feature points out:

One thing that’s making it slightly easier for the old guard to say good-bye is their hatred of the work-from-home era. “It infuriates me to no end,” says one person who reluctantly accepted the buyout. The PRH offices in midtown remain empty as ever. “If you go in there, it’s quite shocking,” says an exec who dropped by recently. “You walk on to one of those floors and there’s literally no one there. Just books in boxes piled up. It looks like a storage house.”

Many of those listed above had versions of the kind of old fashioned publishing careers that remain dominant in the public imagination (three-martini lunches, extravagant expense accounts, glamorous book parties), a professional way of life largely unrecognizable to the majority of the thousands of lower level workers that actually get books published.

Nonetheless, the loss of so much brilliant institutional knowledge—and the well funded editorial risk-taking that so often went along with it—is a sad moment for literary culture. –JD

29.

Reading became . . . cool?

Odds are that, if you’re reading this list, you know that reading is cool and probably have since LeVar Burton told you so when you were a child. But 2023 was the year that reading became Cool Again, according to the culture. LA is hosting pop-up readings in parking lots, “Literary It Girls” are now throwing the most exclusive of book launch parties, the Look Book photographed the attendees at Catherine Lacey’s launch event, you can buy a hat plastered with the name of your favorite (dead) author (they got rid of the living-author hats, which was probably for the best), Chris Pine keeps being spotted with bags of books in seemingly every city he visits…

Honestly, if you want a hot tip, we’re betting that next year’s big trends will be everybody ditching their phones to carry around battered Penguin paperbacks in their back pockets, from which they can and will read aloud at the slightest provocation. Also there might be more hats. Watch this space. –DB

28.

Caroline Calloway and Natalie Beach published dueling books.

Say what you will about Caroline Calloway: The woman knows how to capture a headline. Or, in the case of the well-timed release of her self-published memoir, Scammer, wrest the headlines from her best friend-turned-very public bad art friend, Natalie Beach. Beach’s memoir-in-essays, Adult Drama, which sprang from her viral essay “I Was Caroline Calloway,” was released on June 20 by Hanover Square. Calloway’s—originally slated for publication (by her, at the steep price of $65) in 2020, shipped that same month, guaranteeing that it would garner mention (at the very least) in any bit of publicity for Beach’s book.

Becca Rothfeld at The Washington Post had this to say of the dueling memoirs: “Beach is a talented essayist with a promising career ahead of her. Calloway is a lunatic who has already written a masterpiece.” Tyler Foggatt at The New Yorker came to a similar conclusion, writing “Beach’s book is less meandering than Calloway’s, and yet it is also slower and more unsure of itself.”

As you might expect from someone who built an identity from the fetishization of aristocracy, Calloway is an expert at dueling. She doesn’t even need a second. –JG

27.

World’s largest and worst bookstore, Amazon, gets sued by the FTC.

In what is probably the largest suit every brought against the world’s largest distributor of stuff we generally don’t need, the FTC—specifically chairwoman Lina Khan—is accusing Amazon of

…exploiting its monopoly power to enrich itself while raising prices and degrading service for the tens of millions of American families who shop on its platform and the hundreds of thousands of businesses that rely on Amazon to reach them.

That sounds about right. But why is this literary news? Most of you probably know that Jeff Bezos began his little experiment in online shopping with books, a gambit that turned him into the overwritten evil genius caricature he is today, and changed forever the way we buy books—for the worse.

Will this suit change anything? Probably not, but this is likely just the beginning of a protracted effort to rein in the company’s world historical monopoly on what people buy. –JD

26.

Haruki Murakami published a novel (but English speakers did not get to read it).

In March we reported that there would be a new novel by Haruki Murakami but, alas and alack, English readers wouldn’t get to read it. The Japanese publisher pitched the 1,200 page book as: “Must go to the city. No matter what happens. A locked up ‘story’ starts to move quietly as if ‘old dreams’ are woken up and unraveled in a secluded archive.” OK! In April, The City and Its Uncertain Walls (Machi to Sono Futashikana Kabe) was published.

The Japan Times described the book as a novel told in three parts: the “first of which is based on Murakami’s 1980 short story of the same title, which he considered a failed work and had hoped to return to one day. In it, a male narrator seeks out a girlfriend from his teenage years, and moves between the real world and a fantasy city surrounded by a very high wall. In part two, the protagonist leaves his job to work in the library of a new town, and in part three, the story returns to the walled city.”

Trolling Reddit threads and Japanese discussion boards via Google Translate, it seems the book treads similar ground as Murakami’s 1985 novel Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World but has been appreciated by fans for being a good example of Murakami’s signature style. According to distributors, the novel is the top-selling book across genres for the first half of 2023, beating out a guidebook for the latest Pokemon game on Nintendo Switch. We’ll keep our fingers crossed for the English translation before too long. –EF

25.

Wired published a pretty mean profile of Brandon Sanderson . . . and Sanderson responded.

Perhaps the fact that Mormon fantasy author Brandon Sanderson made $55 million in 2022 started things off on the wrong foot. For Wired senior editor Jason Kehe, that was the peg on which to hang a profile of the author, “Brandon Sanderson Is Your God,” which was published to . . . quite a bit of drama, it turned out, in March.

“How’d he do it? Why now? Is Brandon Sanderson even a good writer?” he asked, embarking on a quest to Utah to find out.

The result is an author profile that is either incredibly mean or lightly elitist, depending on your interpretation of Kehe’s text, and your personal stance on the quality (Stanley Fish? Are you out there?) of Wheel of Time (Sanderson authored three books, and the series was adapted by Netflix), and his dozens of other works from the “Cosmere” and “Cytoverse” (worlds in which he is much richer than a magazine writer).

Does Kehe insult Sanderson’s writing, or Sanderson, or Sanderson’s Mormonism in this piece? Yes. All of those things. Some grabs from which you can make your own assessment:

“Sanderson is extremely Mormon. What makes less sense is why there’s a hole the size of Utah where the man’s literary reputation should be.”

“…none of his self-analysis is, for my purposes, exciting. In fact, at that first dinner, over flopsy Utah Chinese—this being days before I’d meet his extended family, and attend his fan convention, and take his son to a theme park, and cry in his basement—I find Sanderson depressingly, story-killingly lame.”

“My god. Here’s a sample sentence: ‘It was going to be very bad this time.’ Another one: ‘She felt a feeling of dread.’”

This goes on and on. Kehe’s chief criticism of Sanderson is that the author is simply too prolific to be good (he notes a diagnosis of graphomania; a manic compulsion to put words down).

Breaking every rule in the author’s handbook (apparently, according to Kehe, not for the first time), Sanderson responded via Reddit, home turf for Wheel of Time fans, in a well-written and occasionally VERY SHARP yet kind response (this feels like the most “extremely Mormon” thing I can identify, if you wish to allow such rhetoric, and the best rebuttal, thank you Emily Temple, of Kehe’s critiques of Sanderson’s keyboard skills). Sanderson’s best “take” on the profile:

[Kehe] seems to be a sincere man who tried very hard to find a story, discovered that there wasn’t one that interested him, then floundered in trying to figure out what he could say to make deadline.

I would argue this was deadlier than anything in Kehe’s profile. So what was Kehe trying to do? Part of me wants to read the piece as a meta-commentary on the kind of immersive latter-day gonzo journalism that places the cynical journalist in the center of the story and the subject as the sidekick (“The Full Tatum”; “Can You Say … Hero?” (I liked both of these, but you know)), or perhaps it’s a meta example of the lamestream media ignoring, then “discovering” a story years later, or an intellectual look at the geography of power in late-capitalist America (San Francisco may have corporate campuses, but Utah has Goblin Valley!).

Or maybe we can take Kehe at face value and assume he pitched a story, went on assignment, then found very little to string together while standing at his desk in San Francisco in his Patagonia vest. (Still, the Dragonsteel conference sounds like something!)

Negative reviews and profiles are vanishingly rare these days, because, as people have noted, those trying to sell books and solicit blurbs are the same people writing reviews for the most part, so you can understand the thrill of publishing something willing to go against the grain (and to court those lucrative hate clicks).

Finally, I am sorry that Salt Lake City’s dim sum received such a beating, surely not deserved. –JM

24.

A romance writer who faked her own death returned to the Facebook group where it all began.

It’s a story worthy of a romance novel, or at least a soap opera: a self-published romance author who reportedly committed suicide in 2020 after being bullied in a Facebook group announced in January (on that same Facebook group!) that she had not in fact taken her own life! The story has plenty more twists (apparently she created a fake account and used that account to ultimately take over moderation of the Facebook group) and unsurprisingly the community didn’t take any of them terribly well. In the wake of these revelations, Laura Miller at Slate coined Meachen’s Law: “The longer a tightly-knit internet community exists, the more the likelihood that someone will fake their death approaches one.”

It’s easy to make light of this story (and certainly we expect to see some of its details powering the engines of pulpy plots for years to come) but once you push past the lurid details, it’s hard not to think poorly of everyone involved. The Internet, it seems, continues to bring out people’s worst behavior — whether that’s bullying, faking your own death, or otherwise trying to serve up what folks believe to be karmic retribution for perceived slights. And to think, this was the year I decided to start reading romance novels because everybody told me the community was incredibly supportive and kind! (Which, to be fair, they mostly are!) –DB

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, you can contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 at any time day or night to speak with trained counselors.

23.

The Internet was convinced that Taylor Swift had written a book.

In May, the Internet was in a furor over a certain, then-forthcoming nonfiction book, a 544-page memoir (including 40 full-color photographs) that was slated to be published by Flatiron on July 9th. Why? Because The Internet thought it was probably written by Taylor Swift.

It all started when the owner of indie bookshop Good Neighbor Bookstore posted a video on TikTok reporting that a major publisher had informed them of a secret book coming in July, and speculated that it might be by the singer, citing various Easter eggs and clues. The publisher quickly asked the bookseller to take the video down, but of course, nothing can truly be deleted anymore.

A screenshot originally posted to Reddit showed notes from sales rep Anne Hellman on Edelweiss indicating a few more hints: that the book had an announced first print run of 1 million copies, that it was “fun and NOT political,” and the title would be announced on June 13. Hellman also pointed out that July 9th—the worldwide pub date—was a Sunday, an unusual day for a book to be published, and that booksellers who wanted copies in advance had to sign an affidavit.

The Swifties, unsurprisingly, went deep. Some even theorized that that not only would Taylor be publishing a memoir, she’d be using it to come out. Alas (?), once actual publishing people got wind of the rumors, it was quickly confirmed not to be a Taylor Swift book, but rather, a BTS book. (July 9 being, apparently, Army Day.)

Did it sell like hotcakes, even though Taylor didn’t write it? It did indeed. –ET

22.

James Daunt puts the books back into Barnes & Noble, and it’s working.

I’m old enough to remember when Barnes & Noble was the big bad enemy box store, muscling into our charming little neighborhoods, taking all the business away from our delightful indie bookstores and our mom-and-pop coffee shops (I mean, they even made a famous documentary about it).

But then came the internet, and Amazon (see 27 above). So we realized that Barnes & Noble wasn’t exactly the enemy, and that for a lot of communities outside those charming, gentrified little urban neighborhoods, it served as both meeting place and starting point, for seniors in need of a place to read the newspaper, and for awkward teens looking for something—anything—to reveal a bit more of the world.

So now I find myself rooting for Barnes & Noble, and for former Waterstones CEO and bookstore whisperer James Daunt, whose tenure thus far as Barnes & Noble head honcho has surpassed expectations. The key to a successful bookstore, it turns out, is books. As Daunt told The Guardian in April:

[Now] you’re not seeing much beyond books. I mean, there are other things, but it’s unequivocally book-driven. Amazon doesn’t care about books … a book is just another thing in a warehouse. Whereas bookstores are places of discovery. They’re just really nice spaces.

This revolutionary focus on… books in bookstores has yielded very positive results. After having closed nearly 400 of its 1,000 US stores over the last decade, Daunt’s leadership has seen nearly 30 new stores open in 2023.

The margins for bookselling will always be tight, and there’s no guarantee Daunt’s initial successes can be sustained over time, but in a business accustomed to bad news, this is a nice change. –JD

21.

Spotify makes its big move into audiobooks.

As I wrote way, way back in August, 2020, when it first became clear Spotify was going to move into the audiobooks space:

The biggest question (for me, anyway, as an audiobook reader and Spotify user) is how the hell Spotify plans to bring the one-price-for-infinite-songs subscription model to books. On the one hand, I imagine publishers are glad to see a potential and legitimate competitor enter the playing field to provide an alternative to Amazon’s incredibly aggressive contract stipulations (look, I love these guys, but I don’t think Bezos and co. are all that worried); on the other… UNLIMITED BOOKS WHAT NOW?!

Well, as of September 2023, Spotify is officially in the game, offering over 300,000 titles for purchase, a la carte. But here’s the scary new part: as of last month in the US, nearly 150,000 titles are available on-demand for premium members, just like songs or podcasts. And if you know anything about what Spotify has done to the livelihoods of musicians, this has to be scary as hell for writers. Maybe having everything you could ever possibly want available at any moment isn’t such a great idea? –JD

20.

BookTok moved into publishing.

BookTok, eh? What’s it’s all about? How does it work? Why are its users so obsessed with Madeleine Miller’s The Song of Achilles? I, a hapless luddite, still don’t know the answer to any of these questions, but I do know that the subcommunity is a powerful new player in the literary landscape, and woe betide anyone (me) who doubts its ability to move copies and shake up our dusty old industry. Case in point: in July, the New York Times reported that ByteDance (TikTok’s parent company) had recently filed a trademark for a publisher (8th Note Press), hired a romance industry veteran as an acquisitions editor, and begun courting self-published romance writers to join its stable. Given that ByteDance has direct access to an audience larger than any traditional publisher could ever dream of and therefore could, in theory, boost its own authors at the expense of all others, the question must now be asked: is it only a matter of time before the Knopf Borzoi, the Random House penguin, and the Simon & Schuster guy with hat are each forced to bend the knee in supplication to publishing’s new overlord? –DS

19.

When Winnie-the-Pooh entered the public domain, horror followed.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that as soon as intellectual property hits the public domain, it will be immediately twisted far beyond the creator’s wildest dreams. It’s hard to imagine how A. A. Milne would react upon seeing even just the trailer for Blood and Honey, wherein a forgotten Pooh, Piglet, and co. have gone feral in Christopher Robin’s absence and are… *checks notes* now slasher villains hunting Christopher, his girlfriend, and their friends. It sounds absurd, and it is! But honestly, it’s also a hell of a lot of fun! Proper B-movie slasher silliness, as opposed to the increasingly ponderous and altogether un-fun vibe coming off of basically every other long-running franchise that keeps going back to the same well instead of getting strange with their IP.

Combined with a burgeoning wider acceptance for fan-fiction in general, there’s palpable joy out there at seeing artists go to the mat with wild ideas that play in established sandboxes. Obviously it can go too far (the director of Blood and Honey has expressed interest in a childhood-horror ‘shared universe’ involving the Hundred-Acre Wood characters as well as at least Bambi and Peter Pan) but honestly, if Sherlock Holmes can fight Dracula, why can’t Eeyore take his rightful place upon a throne of skulls and cover all the lands in a second darkness? –DB

18.

Jon Fosse won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

After a decade near the top of Ladbrokes’ list of odds, 2023 was finally Jon Fosse’s year, with the 64-year-old Norwegian receiving his call from the Swedish Academy, rather fittingly, while walking alongside a fjord. Perhaps best known to Anglophone readers for Septology, a single-sentence, seven part, 672-page novel (deftly translated by Damion Searls) that combines the domestic and spiritual in incantatory prose, Fosse is possibly more famous abroad as a playwright, with over 1000 productions of his work to his name.

Interestingly, Fosse writes in Nynorsk—a standard form of Norwegian based on Norwegian dialects, as opposed to Bokmål, which is based on the written grammar of Danish. Between 10-15% of Norway’s 5.4 million citizens use Nynorsk as their official language, or roughly 800,000 people, meaning that this is the first time in several decades that the Nobel hasn’t gone to an author writing in one of the “major” languages. The Nobel might be the biggest literary prize Fosse can aspire to in this life, but there might be something greater waiting for him in the next. In 2012, Fosse quit booze and converted to Catholicism, something the Vatican itself seems to have noticed, with the Pope writing to Fosse in December and invoking upon him “an abundance of divine blessings.” –SR

17.

Michael Oher, the subject of Michael Lewis’s The Blind Side, filed a suit against the Tuohy family.

I’m not going to say anything here about Sandra Bullock and her acting chops, because my opinion on that matter tends to cause friction, but if you can remember the 2010 Oscars, the film The Blind Side was a big winner on the night, netting Bullock a statuette for best actress while the film itself won best picture. In broad strokes, it was a feelgood true story about how a white family (the Tuohys) adopt a young Black man (Michael Oher) from an impoverished background, helping him attend Ole Miss and eventually make it to the NFL.

But in court filings in Shelby County, Tennessee earlier this year, Michael Oher alleged that in February 2023 he discovered that he had never been adopted, but instead placed in a conservatorship, which allowed, and continues to allow, the Tuohy family to make financial decisions on his behalf. For their part, the Tuohy family maintain they never claimed to have adopted Oher—he was over 18 at the time the agreement came into effect, meaning adoption was no longer an option—and that the conservatorship was the most legally practical option at the time. As with Britney, a conservatorship is usually put in place when an adult individual has mental or physical disabilities, which was never the case with Oher. Oher asked the judge to end the conservatorship with immediate effect and asked for a forensic accounting of how the profits from his life story—developed by Hollywood into film that went on to make over $330 million—were dispersed. The matter remains before the courts.

So, how is this a literary story? Well, you have to wonder how much Michael Lewis, author of the book, knew about the finer details of this story, and perhaps also how much he stood to profit from the wheeling and dealing and percentages granted once his book was optioned. The story broke at around the same time Lewis’s highly-anticipated biography of Sam Bankman-Fried, the now-convicted founder of crypto platform FTX, was ramping up its publicity cycle. There were angles of interest for those into biography-as-form and crypto-as-real in this book, as Lewis had been granted unprecedented access to Bankman-Fried’s Bahamas compound, and it had been reported that Lewis’s approach to biography was in fact something more like hagiography. To top it all off, the book (Going Infinite) was embargoed lest it affect the court case. Fast forward a couple of months, you have reports of Lewis sitting on the Bankman-Fried family’s side of the courtroom through the trial, but when the book came out, it received middling reviews, with Zeke Faux’s Numbers Go Up rating several mentions during the trial and emerging as the more authoritative SBF bio. –SR

16.

Everyone realized (finally, again) that Goodreads is terrible.

Goodreads is terrible. Everyone knows this. Amazon owns it! But because there’s no viable alternative, people just keep using it. Still, every once in a while, everyone remembers that Goodreads is terrible at the same time—this year it was because of the Elizabeth Gilbert thing, which you’ll find a little further down our list—and then we get a bunch of articles about it.

“The terrible power of Goodreads is an open secret in the publishing industry,” wrote Helen Lewis in The Atlantic. It can help a book succeed, or it can, possibly, destroy a book before it has even been published (that is, before anyone has actually read it).

What tends to happen is that one influential voice on Instagram or TikTok deems a book to be “problematic,” and then dozens of that person’s followers head over to Goodreads to make the writer’s offense more widely known. . . . When the complaints are more numerous and more serious, it’s known as “review-bombing” or “brigading.” A Goodreads blitzkrieg can derail an entire publication schedule, freak out commercial book clubs that planned to discuss the release, or even prompt nervous publishers to cut the marketing budget for controversial titles.

Over at Shondaland, Greta Rainbow called the site “beige in every sense of the word” and wrote: “A San Francisco couple initially built it for their friends to compare the popularity of Dune versus Pride and Prejudice. Now, ads for Prime shows splash on the home page. The algorithm gives Ferrante fans links to textbooks in Italian.” Useful!

“It is, in fact, possible to have a decent time on Goodreads,” wrote Tajja Isen in The Walrus. “You just have to ignore everything about the way the site is designed and how you’re supposed to use it.”

Cool. But why bother, when it seems to bring out the worst in people—as evidenced by this recent story, in which a debut fantasy author with a two book deal admitted to “review bombing” other debuts and making fake accounts to give her own (unpublished) book five stars. She was then dropped by her publisher.

By the way, if you find yourself unable to understand why your favorite book has three stars on Goodreads, we have the answers for you. –ET

15.

Everyone realized (finally, again) that blurbs are terrible.

You know what’s worse than Goodreads? Blurbs. For some reason, 2023 was also the year we all remembered that.

“On their surface, book blurbs seem fairly innocuous, but in reality, they’re a small piece of the puzzle with a big impact—one that represents so much of what’s broken within the traditional publishing establishment,” wrote Sophie Vershbow in Esquire. “Blurbs expose this ecosystem for what it really is: a nepotism-filled system that everyone endures for a chance of ‘making it’ in an impossible industry for most. To borrow a phrase from Shakespeare enthusiast Cher Horowitz, ‘Blurbs are a full-on Monet. From far away, they’re okay, but up close, they’re a big old mess.'”

It’s true. Everyone hates them—but authors especially, who are often either groveling for them or being groveled at for them, neither of which is remotely pleasant. And then there’s the fact that they’ve become more divorced from reality—and therefore pointless—than ever.

“Blurbs have always been controversial—too clichéd, too subject to cronyism—but lately, as review space shrinks and the noise level of the marketplace increases, the pursuit of ever more fawning praise from luminaries has become absurd,” writes Helen Lewis in The Atlantic. “Even the most minor title now comes garlanded with quotes hailing it as the most important book since the Bible, while authors report getting so many requests that some are opting out of the practice altogether.”

“Within the blurb ecosystem it is generally understood (perhaps cynically) that ‘blurbspeak’ is, as [David Foster] Wallace noted, ‘literally meaningless,'” wrote G.D. Dess in The Millions. “(And the jury is still out as to how much they actually help increase book sales.)”

Who will save us, then, from the tyranny of the blurb? (No one. The answer is no one. See you again in a couple of years.) –ET

14.

It was the Year of Judy Blume.

To be fair, it’s always sort of the Year of Judy Blume, because Judy Blume is eternal. But at the very beginning of 2023, we were treated to the first trailer for the long-overdue adaptation of beloved Blume classic Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, and it was clear things were going to be turned up a notch this year. Not only did we get Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret (which turned out to be wonderful) in April, but also Judy Blume Forever, a documentary about the life and legacy of the 85-year-old writer, in addition to a healthy number of contemporary authors reflecting on the importance of her work, both personally and, you know, to the world.

“Judy’s writing helped me to honestly play a teenage girl because her books helped me become one,” wrote Molly Ringwald in her citation for Blume in TIME‘s 100 Most Influential People of 2023.

At a time when no one was chronicling the monumental minutiae occupying a young person’s brain—body shame, bullying, grief—there was no subject that Judy wasn’t up for exploring in her books. Even the most taboo subjects of the time—menstruation and masturbation—were examined, helping millions of young women to enter young adulthood a lot more informed and a little less afraid. Her books have been banned many times in various places over the years, since there are always people for whom the thought of an empowered young woman’s autonomy over her mind and body is objectionable. But good books will find their way into kids’ hands, and I’m so grateful they found mine.

Same! –ET

13.

So many beloved literary magazines closed. . .

Let’s hope this isn’t a story we have to run every year. In recent times we’ve seen the shuttering and resurrection of The Believer, the loss of Astra Magazine and Gawker, and unfortunately 2023 was no different.

Across the pond, The White Review, founded across the pond in 2011 by Ben Eastham and Jacques Testard (who would go on to e-Flux and Fitzcarraldo Editions, respectively) finally reached the end of its financial tether, reportedly due to a combination of factors, including a declining appetite for literary philanthropy, and the non-granting of government funds on which the magazine had been reliant. It leaves a giant hole in the English literary scene, as a publication where many, many contributors were discovered by British publishers, and which from its inception had a commitment to authors beyond the anglosphere. Their last hurrah will be an anthology of translations by writers previously unpublished in English, to come out next year.