How a 20th-Century Czech Play Influences Our Understanding of Science and Humanity

Jitka Čejková Commemorates the Centennial of Karel Čapek’s R.U.R.

Nature discovered only one method of producing and arranging living matter. There is, however, another, simpler, more malleable, and quicker method, one that nature has never made use of. This other method, which also has the potential to develop life, is the one I discovered today.

Any scientist, especially one who works in the artificial life field, would love to make such a groundbreaking discovery, to be the first in the world to share these wonderful words on social media and publish the results in prestigious scientific journals. Unfortunately, another method to create life has not yet been found, and these notes were written in a laboratory book by the fictional mad scientist Rossum from Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R., subtitled Rossum’s Universal Robots.

Karel Čapek (January 9, 1890–December 25, 1938) was a Czechoslovak writer, playwright, and journalist. I don’t believe he ever had an ambition to be one of the “firsts” in the world, but in the end he was. With his brother Josef he invented a new word—robot—and he was the first to use this word for an artificial human, formed from chemically synthesized living matter.

In Czech, R.U.R. was published in November 1920 and premiered on January 25, 1921 in the National Theatre in Prague. The play was first performed in English by the New York Theatre Guild on October 9, 1922. It was a great success—by 1923 R.U.R. had been translated into thirty languages. And the word “robot” remained untranslated in most of these.

What has always fascinated me most was how many of these contemporary questions were already heard in Čapek’s century-old science fiction play.Soon the word “robot” started to be used for all sorts of things, and Karel Čapek, instead of being happy at its fame, was upset and frustrated. He protested against the idea of robots in the form of electromechanical monsters that fly airplanes or destroy the world by trampling. His robots were not made of sheet metal and cogwheels; they were not a celebration of mechanical engineering!

In a column in the newspaper Lidové noviny in June 1935, he emphasized that when writing R.U.R. he was thinking instead of modern chemistry. Although it was the chemistry of the time, without concepts like DNA or RNA, his statements were quite timeless (as is all of R.U.R.). He laid stress on the idea that one day we will be able to produce, by artificial means, a living cell in a test tube.

That we will be able to create a new kind of matter by chemical synthesis, one that behaves like living material; an organic substance, different from what living cells are made of; something like an alternative basis for life, a material substrate in which life could have evolved, had it not, from the beginning, taken the path it did. He emphasized that we do not have to suppose that all the different possibilities of creation have been exhausted on our planet. His texts were such a brilliant ode to artificial life!

However, in Čapek’s lifetime there was no developed scientific field of artificial life (commonly abbreviated as ALife). This emerged several decades later. It is generally accepted that the modern field of ALife was established at a workshop held in Los Alamos in 1987 by Christopher G. Langton. The field focuses mainly on the creation of synthetic life on computers or in the laboratory, in order to study, simulate, and understand living systems.

Originally the field was a conglomerate of researchers from various disciplines including computer science, physics, mathematics, biology, chemistry, and philosophy, who were exploring topics and issues far outside of their own disciplines’ mainstreams, often topics of foundational and interdisciplinary character. These “renegade” scientists had problems finding colleagues, conferences, and journals in which to disseminate their research and to exchange ideas.

For this rich and diverse set of people, ALife became a new home, a “big tent,” unifying them especially in two main conferences (the International Conference on the Synthesis and Simulation of Living Systems, and later also the European Conference on Artificial Life, with meetings in alternating years) and one scientific journal (MIT Press’s Artificial Life).

Today, artificial life researchers meet annually at conferences simply titled ALife. I have attended many of them, and always it thrills me to see what kinds of topics are presented and how many views on a specific problem are offered during the discussions. The common characteristic of all researchers in the ALife community is their open mind. It really is a radically interdisciplinary field that cannot be defined either as pure science or engineering. It involves both, employing experimental and theoretical approaches, and the research is fundamental and mainly curiosity-driven.

Practical applications come as by-products, but they are not the goal. There are so many basic questions that we are still unable to answer, such as “What is life?”, “How did life originate?,” “What is consciousness?” and more. Many of these questions are related not only to science but also to philosophy. And what has always fascinated me most was how many of these contemporary questions were already heard in Čapek’s century-old science fiction play.

And therefore I often introduced and praised Čapek’s R.U.R. in my talks at conferences, but also in scientific papers, in normal conversation, everywhere! Not only because I wanted to call attention to all of the fascinating open questions related to artificial life that Čapek outlined, but also to point out that the original robots were made from artificial flesh and bones, which was always surprising information for many people.

Moreover, I wanted to remind the world of the Czech giant, Karel Čapek, who was nominated seven times for the Nobel Prize in literature. Of course, I also like his other works. Since childhood I have loved his books Nine Fairy Tales and Dashenka, or the Life of a Puppy. Later I read The Makropulos Affair, The Mother, The White Disease, War with the Newts, Krakatit, The Gardener’s Year, and others.

Some of these works also raise issues related to artificial life (especially War with the Newts), but Rossum’s Universal Robots has become my favorite since I started my doctoral studies in the Chemical Robotics Laboratory of Professor František Štěpánek at my alma mater, the University of Chemistry and Technology Prague.

In fact, the chemical robots in the form of microparticles that we designed and investigated, and that had properties similar to living cells, were much closer to Čapek’s original ideas than any other robots today (“a blob of some colloidal pulp that not even a dog would eat,” as one of his characters puts it).

Currently, in my laboratory I examine droplets of decanol in the environment of sodium decanoate (an organic phase almost immiscible with water in the form of a droplet located on the surface of an aqueous surfactant solution). These droplets are unique in that they somehow resemble the behavior of living organisms.

For example, just as living cells or small animals can move in an oriented manner in an environment of chemical substances—in other words, they can move chemotactically (chase food or run away from poisonous substances)—so my droplets can follow the addition of salts or hydroxides in a very similar way. Thanks to chemotaxis, they can even find their way out of a maze!

Just as living cells change their shape and create various protrusions on their surface, so also decanol droplets are able to change their shape under certain conditions and create all kinds of tentacle-like structures. We also recently discovered that amazing interactions occur in groups of many droplets, when the droplets cluster or, on the contrary, repel each other, so that their dance creations on glass slides or in Petri dishes resemble the collective behavior of animal populations like flocks.

Bottom line, I started to call these droplets liquid robots! Just as Rossum’s robots were artificial human beings that only looked like humans and could imitate only certain characteristics and behaviors of humans, so liquid robots, as artificial cells, only partially imitate the behavior of their living counterparts.

As I mentioned above, R.U.R. was published in 1920. As the year 2020 approached, I felt that we must mark the centenary of this timeless work and celebrate the word “robot” in some way. Some of my ideas were never realized, and some were only partially realized due to the COVID pandemic (we organized the ALife 2021 conference as an online-only event, rather than hosting it in Prague as we wanted). The project I really took seriously was to prepare a book on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the word “robot.” This book would contain Čapek’s original play along with present-day views on this century-old story.

And thus the book Robot 100: Sto rozumů was released by our University of Chemistry and Technology Prague in November 2020, exactly 100 years after Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots. It contained the contributions of 100 people, mostly scientists, but also writers, journalists, radio and television presenters, musicians, athletes, and artists. R.U.R. is a timeless work, in which we can find many topics that scientists deal with even today, whether the synthesis of artificial cells, tissues, and organs, issues of evolution and reproduction, or the ability to imitate the behavior of human beings and show at least signs of intelligence or consciousness.

R.U.R. is a timeless work, in which we can find many topics that scientists deal with even today.R.U.R. also outlines social problems related to globalization, the distribution of power and wealth, religion, and the position of women in society. Every contributor could find an example of how R.U.R. raises some still unanswered questions of their field.

The feedback of readers and the positive reviews encouraged me to publish an English edition. I was pleased that the MIT Press was interested in publishing my book. The key problem, as I had already seen in feedback from contributors, was the English translations of Čapek’s play. Probably the most widely used English translation of R.U.R. is the very first one from 1923 by Paul Selver.

However, it is not a very successful translation, and Čapek himself was not satisfied with it. Not only did Selver leave out some passages, but he even completely canceled the character of the robot Damon. Also, while Čapek’s original consists of a prologue and three acts, in translations we often encounter three acts and a final epilogue. Foreign authors often wrote about Rossum junior as a son because he is referred to as “young Rossum,” but in the Czech original it is clearly stated that he was the nephew of the older Rossum.

Another difference was Domin’s request for Helena Glory’s hand—while in the Czech original he only places both hands on her shoulders, in Selver’s translation he even kisses her. Inconsistencies in the translations were mostly easily solvable trifles, but sometimes they complicated the content of the entire essay.

It was clear that if we published Robot 100 in English, it would require a completely new translation. I am happy that Professor Štěpán Šimek agreed to translate the first edition of Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots. I was so happy when I obtained his comments to the translation: “This is a straight translation in terms of the original. By that I mean, that unlike some other translations that I’m familiar with, I have not made any cuts, that I have translated every word and line, and that I haven’t changed anything from the original. While the play has some obvious dramaturgical flaws, I have not tried to correct those in the translation. I believe that cuts, rearrangements, dramaturgical clarifications, and stuff like that are the job of the potential director and/or dramaturg, not the translator, unless the translator is asked to create an adaptation of the original. In other words, this is a Translation, not an Adaptation.”

And I was amazed when I read the new translation. It is excellent and it fulfills my expectations. Thanks to Štěpán Šimek’s work, this book offers English-speaking readers a truly faithful translation of Čapek’s R.U.R.

It was obvious that if we published book Robot 100 in English in 2023, it would require a new title, because there is no centenary this year. We also decided not to include the contributions of all one hundred of the contributing authors in our print edition, but to select mainly those related to artificial life, and to publish the rest online.

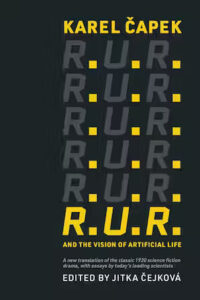

Finally, we have chosen the title R.U.R. and the Vision of Artificial Life. This title perfectly reflects what the readers will find within—the century-old play R.U.R in a completely new and modern translation by Štěpán Šimek, and twenty essays on how Čapek’s brilliant play has the prescient power to illustrate current directions and issues in artificial life research and beyond.

__________________________________

From R.U.R. and the Vision of Artificial Life by Karel Čapek, edited by Jitka Čejková. Copyright © 2024. Available from MIT Press.