The winners of the 74th National Book Awards—given every year in Young People’s Literature, Translation, Poetry, Nonfiction, and Fiction—will be announced next week in a ceremony hosted by LeVar Burton at Cipriani Wall Street in New York City (and online).

Ahead of the festivities, Literary Hub caught up with (almost) all the finalists to ask them a bit about their books, their reading habits, and their writing lives.

FICTION

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, author of Chain-Gang All-Stars

How do you tackle writer’s block?

By writing. I don’t say this in a flippant “haha” way. I say it meaning I try my best not to assign to myself a state where I absolutely cannot write. And so I try to remember the fun of writing the play aspect. If I’m in a project I try to think about how just writing a single word, then another then another is all I’m doing. When it is difficult, which is often I allow myself to try my best in a specific amount of time and if nothing comes then I’m okay with that. (I’m not but I tell myself it’s okay.)

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

I think in general we need to remember that no advice is catchall for everyone. And so bad advice is usually just bad advice for you. It might be great for someone else. I think the worst advice is that which situates itself as an absolute. I think the best advice I’ve been given which was given directly to me in consideration of my tendency to get bogged down in some of the less important parts was: be simple, be precise. Also a bonus from Dana Spiotta: A story needs to swerve.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I like this question. I have a lot of people who have been insanely impactful but I think I’d say Lynne Tillman at the State University at Albany has the hugest impact. Working with her was my first real time seeing myself as a writer and also being acknowledged as such. She taught me that aggressive line edits are a love language so I was and am never resistant to receiving them. The made me feel like I could do this thing that was as far as I could tell impossible. She also introduced me to a lot of the other writers I’ve come to love and led me to knowing what an MFA even was so yeah, Professor Tillman changed my life.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I want to talk more about the costumery associated with being a writer and the weird hierarchal elements we preserve to the detriment of basically everyone. I do end up talking about it but usually in the context of pushing back against the idea that, for example, a short story is less creatively ambitious than a novel.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Make music (album coming soon but that’s still a writer so let me think of something else.) I think I’d be involved in directing probably (also often associated with writing kinda). Maybe I’d be a filmmaker/photographer. Yeah.

Aaliyah Bilal, author of Temple Folk

Who do you most wish would read your book? (your boss, your childhood bully, etc.)

Barack Obama. I imagine him sitting in his study reading Temple Folk.

What time of day do you write (and why)?

Always in the afternoon. Morning is too mentally chaotic for me.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I respect writer’s block. I wouldn’t tackle her. I try to sit patiently and ask myself what it is that I’m not seeing. The right words are often on the other side of experiences we are avoiding.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you ever received?

“Sit down and just write.” It’s important to think clearly first. Forced words makes for bad writing.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

Learning different languages as well as learning to read music have had the greatest impact on my writing. They add dimension to my thought process.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

It might surprise readers to know that most of my process is prior to language. The reader sees the words, but in my mind they are oils and acrylics.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

“Blue in Green” is my all-time favorite song.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters. It’s a story that really troubles me now, but I remember loving that book as a kid. As for chapter books I loved a middle grade novel called Jacob have I Loved. I loved that the setting was in my home state of Maryland, but especially connected to the protagonist’s struggle as a very special girl who was belittled by her family.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Aside from Edward P. Jones, I’ve read the collection Everything that Rises Must Converge several times. I know Flannery O’Connor is out of fashion with a certain kind of reader. I agree that the way she wields race is lazy, but the technique impeccable.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I play solitaire.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison. I wanted to fly after reading that book.

How do you decide what to read next?

My work dictates my reading.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

I would have benefited from bell hooks’s Sisters of the Yam. It would have helped counteract some of the unhealthy ways I learned to think about gender and race as a kid.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

It’s rare that anyone asks me about the individual stories within Temple Folk, just the ideas behind the book.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

I wish I were funny enough to be a comedian. Making people laugh feels like power to me. I’d be that or a bass guitarist. That would be so fun!

Paul Harding, author of This Other Eden

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I write wherever and whenever the spirit strikes. I think I’m probably always turning sentences and words and riffs around in my head, so whenever anything clicks, I write it down on whatever’s handy. I always have a writing notebook around, but I also have dozens of Post-It Note pads of various sizes all over the house and in my work bag, too. Periodically, I’ll go around and scrape up all the Post-It Notes that are stuck on books and walls and tables and tape or staple them into the current writing notebook, then put them all into the master manuscript at hand or, if they’re just orphan ideas or images or whatever I’ll put them into some sort of “miscellaneous” document.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I’m not sure it’s the same these days, but there used to be a prevalent idea that you needed to sit down every day and “face the blank page.” That seemed pretty foolish to me. Why waste time staring at a blank page when you could be listening to great music or reading a book or looking at a painting or taking a walk? To me, writing is not the same thing as, say, typing. If I’m awake, I’m writing, that is, composing, if it’s just in my head. I think I’m probably composing or riffing half the time I’m asleep, too! I love lying on the couch, half asleep, riding the updrafts, as I call it.

How do you decide what to read next?

One of the hardest things for me to do when I first got the fever to read the best books I could get my hands on was to find the best books. Pre-internet, I’d just haunt bookstores and at first the only real standard I used, if you could call it that, was to go down along the fiction shelves and look for the widest spines I could find. I loved huge books, the longer the better. Nothing like that joy of finding a book you love and seeing that you have, like, six or seven hundred pages left to just live in over the next days or weeks. That’s how I found writers like Carlos Fuentes (Terra Nostra), for instance. I looked up some of his essays and found that he loved Thomas Mann, so I picked up The Magic Mountain next. I found out who Mann liked and read whoever that was. Eventually, I ended up with an inexhaustible reading list. There are so many books I’d love to read I’ll never run out. I don’t really decide what to read next anymore; the books just seem to pile up everywhere in the house. I just kind of waft around reading in a dozen or two books at a time. They all sort of mix up with one another and synthesize with one another and suggest all kinds of ideas and idioms and images I’d never be able to conjure on my own.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

No hesitation; I’d be a musician. I played drums for many years in bands, and I still do, in the basement, for myself. I’d kill to play in a good band again, in fact. I was never good enough to be a session player. That’s a whole other order of artistry. But if I could, actually, I’d be happy to be, like, a fourth assistant gofer at a good recording studio. Nothing I loved more back in the day than just being in the studio with a bunch of great musicians and producers and engineers, putting music together.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

It wasn’t so much specifically bad advice, but when I started trying to write fiction there was still a read danger of running into teachers, editors, writing programs who or that presented one or another particular genre or idiom as the be all and end all of how “real” writing just had to be done. Back then, the standard I kept running into was what might be called the Church of Saint Raymond Carver. I love some of Raymond Carver’s stories—some of the most beautiful, artful stuff I’ve ever read. But if I had had to write stories like his, I’d have become a plumber decades ago. Every person should write exactly what seems true and fine and honest to themselves, to their own soul. I shudder when I think of the universes of art and beauty that may well have been lost because some genius followed someone else’s path rather than her own.

Hanna Pylväinen, author of The End of Drum-Time

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

I was in the one of my phases of anxiety that there was no point to writing The End of Drum-Time—no point for me in particular to write it, but also no point in writing fiction at all; by then I’d done so much research I could have written a good deal of nonfiction about the place and era, I mean, if I’d wanted to—but there I was, making up things that definitely hadn’t happened, but using one or two real people from the past, and not others—there seemed to be a basic stupidity to the project of being a writer. I was discussing this with a friend in Sápmi and she said—well, if you were an artist you would paint it. And if you were a singer you would sing about it. But you’re a novelist and so you write a novel about it.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I don’t want to imagine my life without Bach; I would have lost out on so much feeling. If I have to choose which Bach I’d have to say the first movement to his G minor violin sonata, in part because it was once incredibly hard for me to learn, and because it remains so difficult to play, and because when I first heard it I thought it was a little ugly—but that was because I didn’t know it yet. It required so much of me and taught me the value of art that asks a lot. I love in particular how demanding it is in its slowness and how notes in a given chord drop out—it’s quite difficult though it doesn’t sound so, it’s not a show-off piece—but if you are a violinist you recognize its secret trials, and you respect the player who can do what Bach intended, which is to wound you and restore you to yourself.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

I fell in love first with Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, because it was about a little girl who also loved to read, and because it was the first book that transplanted me completely to a life unlike mine and made true the adage, a writer’s job is to make the unfamiliar familiar, etc.., so that the details of Francie’s life, the particularity of the poverty of the Williamsburg slums she was in, became commonplace to me, in part because Francie’s world is filtered through her particular feelings––it is not just that there is a rich girl named Mary who wants to give away a doll to some poor girl named Mary but that Francie despises her, is humiliated by her, and still raises her hand to claim the doll for herself…which is to say Francie is the first character of contradictory impulses that I wanted to befriend. Years later someone explained to me that “the Tree of Heaven” which is, in fact, the tree that grows in Brooklyn, is a weed, and I was dismayed for Francie, as if she were a real person whose feelings could be hurt by this.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I tend to read old books with too many characters. Give me a Russian with four Alexeis any day. Or even a parlor room, or a neighborhood—worlds of judgment or gossip where people are constantly getting in each other’s way, changing each other’s lives in silly little instances. The Heat of the Day by Elizabeth Bowen is like this, foregrounded in coincidental shoulder-jostling—half the time you have no idea why you are following a particular character, but I enjoy it, because I trust her as a writer to not waste my time and indeed she never does.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

I think we could all do more with more discussion of the systemic lack of support for the arts in this country that makes it incredibly difficult—nearly impossible—to have time to write, or compose, or make art of any medium. Whenever I see a great work of art or read an excellent book I always think, now how did they get the time to make that? Who or what supported them? As such my interest in a writer’s life is rarely one of process, but one of life: how did they manage to have a process at all? It’s such a luxury. A room of my own sounds wonderful, but what about four uninterrupted hours a day? I’d settle for two.

Justin Torres, author of Blackouts

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Some good advice I received early on: Pay attention to each sentence. But the best advice is even more general: Slow down.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I’ll talk a bit about my high school English teacher, Laura Iodice, who taught me new ways of reading and relating to the text. She was fiery, from the Bronx, with a fuhgeddaboutit accent, and somehow, like my parents, had ended up far, far upstate, in a very small town. What brought her there I don’t recall, but what luck for me. She felt immediately familiar, and she recognized something in me as well. She plucked me out of one English class and enrolled me in the honors class instead. There, she taught us about Jungian archetypes; she taught Beloved; she taught us existentialism; she essentially taught us critical race theory, though no one called it that at the time. On the side, outside the regular curriculum, she would slide me books, just for me – difficult books she knew I could not fully understand, but somehow needed: Neitzshe’s Human All Too Human, Sartre’s Nausea, Ferlinghetti’s Wild Dreams of a New Beginning. She introduced me to the Puerto Rican writer Irene Vilar, and her book, A Message From God in the Atomic Age. Inside the jacket flaps she would inscribe personal messages, wisdom, much of it, again, went over my head. But as I read, I began to decode what she was trying to tell me. I had lost a lot of faith in the world, and she thought I might find it again in literature. I had her for both junior and senior year. Difficult years. I was in a very dark place. I remember each and every book she gave me. I would stare at the titles (the titles alone!) in amazement. I’d think, I want to write something beautiful. Then, about midway through senior year I was institutionalized. One day, at visiting hours, she was there. With books. She came back again, with more books. We’ve remained friends through the years, and even when we haven’t spoken in a very long time, she’s a voice in my head. I think of her often.

How do you decide what to read next?

I don’t have a system. I buy books all the time, they stack up. I have another stack of books awaiting blurbs—way more than I will have time to get to. I move between one stack and another, reading the opening pages. Depending on my mood, something or other will grab me, and I’m off. Right now I’m enjoying an advance copy of a biography of Candy Darling, by Cynthia Carr, who wrote the biography of Wojnarovicz.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

I wanted to be a painter. I tried. Acrylic on brown paper bags, which I’d open along the seams. I wasn’t very good. These nude figures, haloed or bleeding, or both. I was young and stretching and imitating (which is to say, I was a hack). I was also broke, and even cheap acrylic paint and cheap brushes were not cheap enough. The equipment required more care and attention and space than I could muster. And I hated to clean up after. Still, today, I wish I could paint. Early on in our relationship, many years ago, my boyfriend bought me a book by the British psychoanalyst Marion Milner, as a gift. (He’s an expert on Milner, who was an incredible woman.) I died when I saw the title: On Not Being Able to Paint. I thought, This is the book I need! I thought it would be about creative frustration, and paths out of frustration, and in a way it is, but it was a much deeper book than I’d imagined, and much more strange and unexpected, and therefore much more useful.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

These days I look for opportunities to call attention to the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. Human rights organizations, the UN leadership and the international community in general are all overwhelmingly calling for a ceasefire—only the US and small handful of countries refuse to sign on. I hope for a shift in public sentiment, a recognition of our government’s complicity in the suffering, and enough public demand for a ceasefire that leaders are forced to listen.

•

NONFICTION

Ned Blackhawk, The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History

Who do you most wish would read your book?

When I first began envisioning this book and eventually writing it, I hoped to get readers to see American history in a different register. I have long believed that the study of American history has failed on a fundamental level to analyze the experiences of North America’s Native peoples and to see those experiences as central to the continent’s overall development. Moreover, many histories of the United States continue to be overly celebratory. So, I begin with a simple question: How can a nation founded on the homelands of dispossessed Indigenous peoples be the world’s most exemplary democracy? How do we reconcile the fact that American democracy was built on Indian dispossession and what has that experience been like for Native peoples? I also write that the exclusion of Native Americans was codified in the Constitution, maintained throughout the Antebellum era, and legislated into the twentieth century, and far from being incidental it enabled the development of the United States. I believe that U.S. history as we currently know it does not account for the centrality of Native Americans. I wanted readers to confront these historical truths—especially students, because they are the future of the field, and scholars, because they have the power to reorient narratives of American history. It was also important to me that this book be read by anyone interested in our history and how Native Americans have shaped and been shaped by the United States.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I wasn’t much of a writer as a young person and did not have a computer until my second year in graduate school. At a key point in my development I had several professors who really pushed me to refine my approach to writing and to bring more focus and clarity to my work. They may not realize the impact that they had but their edits and feedback proved particularly helpful especially with each passing assignment. This focus only intensified in graduate school. I have now been teaching writing for over twenty-five years and draw often upon these earlier experiences. I believe I still have those early papers with their marginal notes.

Which book(s) do you reread?

These days I mostly read to keep up. Native American history is in a period of such exciting growth and richness, and there is a great deal of wonderful work being published all the time. I also have three kids, and generally, I don’t often have the luxury of re-reading books from cover to cover. There are a few titles that I keep coming back to: Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac of the Dead, Barry Unsworth’s Sacred Hunger, and David Remnick’s Lenin’s Tomb. Each is monumental in its own way. These books tell of individuals confronting great tragedy but surviving and resisting. I read each during a time when I was uncertain about my own writing and progress, and while it may sound unusual, I found not only inspiration but also reassurance in them.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I try to write at desks with windows so that I can look out and reflect on whatever I’m doing or supposed to be doing. I also like to peruse library bookshelves to find inspiration, often finding myself absorbed in new and interesting subjects. I may even have a habit of ordering books that I find particularly captivating. Much of this book was written during the summer, and I often took small walks to regain focus.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

Growing up, I rarely encountered any contemporary—let alone positive—representations of Native peoples. I wish I had read Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich much sooner than I did. I find Erdrich’s works to be brilliantly expansive and humanizing, and this book is full of beautiful narratives of families, love, and humor—as well as sadness and tragedy—that are familiar to many Native people.

Cristina Rivera Garza, Liliana’s Invincible Summer: A Sister’s Search for Justice

What time of day do you write (and why)?

With any luck, I write early in the mornings, as soon as I open my eyes but when I’m not fully awake just yet. That liminality, the weaving of dreams and ideas, is both productive and liberating. You would find me wearing pajamas and sipping green tea on those glorious days, completely unaware of time.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

What is that? 😉

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

I read and underlined The Diary of Anne Frank when I was very young, thinking that I too could become a writer. But the book I read and transcribed entire paragraphs from was Pedro Páramo by legendary Mexican writer Juan Rulfo. I did not fully grasp the complexity of themes or the structure of the narrative, but there was an elusive beauty on those pages, a void of sorts, an opacity that continued to draw me in.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I re-read all the time, especially theory books and poetry. I go back, attracted by a strange echo. A reverberation. It´s like visiting an old friend who, not surprisingly, has changed over time. I recently re-read some poetry by Mexican author Rosario Castellanos, which was key in my upbringing. Listening to audiobooks counts as re-reading? During the pandemic, I listened to books I had read when I was very young, curious about what had happened to both of us over the years. One Hundred Years of Solitude, by García Márquez, or Remembrance of Things Past, by Elena Garro, passed the test of time.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I clean my house thoroughly. I sweep and dust and declutter as if my life depended on it. There is something somber around my house when it is sparking clean.

How do you decide what to read next?

I am a voracious but disorganized reader. I pay attention to what friends recommend and I let chance work its wonders. I have been disappointed quite often, but this method has also led me to books I would not go to otherwise. That´s how I run into Milorad Pavic, for example. Or Peruvian author Cesar Calvo. Or Bolivian writer Claudia Peña Claros.

Christina Sharpe, author of Ordinary Notes

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I am a morning person but I don’t have a particular writing schedule. I do a lot of writing, plotting, in my head and I can write any time of day.

What was the first book you fell in love with (and why)?

There are so many. I learned to read when I was 3. This likely wasn’t the first (that would have been Bread and Jam for Frances or Bedtime for Frances) but Bright April is up there. It was the first time I read a book about a little black girl who experienced some of the same things that I did as a child. It was also just a lovely book—illustrations and story.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I am a huge rereader. I reread for teaching and for writing, for pleasure and for work. Among my current most reread are books by Toni Morrison, John Keene, Dionne Brand, Saidiya Hartman and Canisia Lubrin. (I also reread a lot of mysteries….)

How do you decide what to read next?

Recommendations and books by writers whose work I respect. Right now I am reading books by Emily Robateau, Steffani Jemison, Aisha Sabatini Sloan, Justin Torres, and Teju Cole.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Well, I’m also a professor so I do that as well. But if I weren’t a nonfiction writer, I would (want to) be a poet or a visual artist.

Raja Shehadeh, author of We Could Have Been Friends, My Father and I: A Palestinian Memoir

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I write in the morning when my mind is clear before the distractions of the day have begun. I find that at that early hour I can be most creative energetic.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I’ve never experienced writer’s block. There have always been more subjects to write about than I’ve had time to get to them.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

A lot of my writing is done as I walk when ideas, words and a grasp of what I’m writing about comes to me most easily.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce. I appreciated his stream of consciousness style and how the book proceeds from the point of view of the child and develops from there.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich.

John Vaillant, author of Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World

What time of day do you write (and why)?

Morning is that liminal, lucid time when the replenished and still-accessible dreamtime unconscious gets pressurized into the world by incoming caffeine, turning my head into an espresso machine for language.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

A few years ago, Miguel Syjuco told me that Jonathan Dee exhorts his students to write what they want to know. I really resonated to that because it’s what I’ve been doing for my entire career: writing to learn, to push myself beyond my comfort zone, to explore someplace new.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

That would be a toss-up between Miss Gabron, my first grade teacher who sat us all down to write poems, urging us toward essence and economy of language, and my first magazine editors who really took time with my work and pushed on it. Those early editing encounters with thoughtful, patient people who loved language, and who understood that I did, too, are among the greatest gifts I’ve ever received. Reflecting on it now, I realize that I’ve had really attentive, language-loving teachers and readers throughout my life, and I’m deeply grateful to all of them.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

How much time I spend not writing.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Rian Malan’s memoir, My Traitor’s Heart, shook me to the core. Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Suttree both required me to stop reading periodically and reorient myself in the room: “The clock has run, the horse has run, and which has measured which?” Etc.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

The question of whether or not fire is alive.

•

POETRY

John Lee Clark, author of How to Communicate

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t. When Nibby insists on blocking me, I go to a bean bag and let him doze on my lap.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

The Magers and Quinn used bookstore in Uptown Minneapolis. More specifically, the shelved cart they put outside that was always filled with obscure titles, for sale at a dollar apiece. “From Caesar to the Mafia: Sketches of Italian Life” by Luigi Brazini, 1971, is a memorable example.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

The crucial part, when I’m not typing. That’s only transcription, not the writing.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

I remember crying twice while reading, both times over a long poem: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Evangeline” and Robert Francis’s “Valhalla.” As it happens, Longfellow’s “The Spanish Student” was such an insult to me as a member of a marginal community, it made me spit.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

Gossip about my elders, Deaf and DeafBlind poets who tousled my hair and patted my back. Questions I’d love to answer include “Wow, you knew Bob Panara?”, “What did Merv Garretson say about his time in Montana?”, “How did Eric Malkzkuhn sign his emails?”, “Can you show me again how Patrick Grabybill held that glass of wine?”, “No! You didn’t! Not to Bernard Bragg! For real? You rascal!”, “How far down her back did Melanie Bond’s hair go?”, “How about Peter Cook’s hair, and, um, his feet, did you get to backchannel his bare feet?”, “Why did Tim Cook walk with folks in that strange way?”, “What did Bob Smithdas’s letters smell like?”, and “Did you ever manage to ruffle Geraldine Lawohron’s cool?”

![Craig Santos Perez, from unincorporated territory [åmot]](https://s26162.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/71Ygduy3vPL._AC_UF10001000_QL80_-200x300.jpg)

Craig Santos Perez, from unincorporated territory [åmot]

Who do you most wish would read your book?

First and foremost, I write for my family and my people, the native Chamorus. I hope my book will make my community and homeland proud.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

When I have writer’s block, I try to find inspiration by reading and teaching. My students inspire me to keep going. Beyond the literary, swimming, running, biking, hiking, and canoeing connects me to my body and nature, which in turn inspires my writing.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

I had amazing teachers during my MFA education at the University of San Francisco. My most important teachers there include Aaron Shurin, Rusty Morrison, Truong Tran, D.A. Powell, and Rob Halpern.

What was the first book you fell in love with (and why)?

The first book I fell in love with was Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude because of its magical realism, lyrical prose, and memorable characters.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I like to reread T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets every few years.

Evie Shockley, author of suddenly we

How do you tackle writer’s block?

By not believing in it. When I have to write, I write, whether the motivation is external or internal. When I’m not facing a deadline of some sort, I write because an idea is gnawing at me and I’m curious about whether I can get it down on the page in some satisfying way. In those moments where I have the time and desire to write, but find myself with nothing I’ve been wanting to find words for, no new form I’m excited to try, no intriguing language I’d meant to play around with, I put down my pen and go do something else. I’m much more likely to have ideas for poems and no time to work on them than the other way around, but when I come up blank, I don’t think of it as a problem to fix.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

That I don’t have one. (For better or for worse!)

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

I started reading when I was three years old, and I’m sure I loved many of those very early books. The earliest book of any kind that I held dear was a thick volume called 365 Bedtime Stories. Each story was one page long and, as you’ve no doubt guessed, there was one for each day of the year. All the characters lived on a single street that was full of children and, over the months, you’d come to feel that you knew everybody and really cared about their ups and downs. I read them over and over and over for years. I also loved a book of illustrated Mother Goose rhymes, which I quickly memorized. A bit later, as an elementary and junior high school student (no “middle school” back then!), I was deeply in love with books that came in series, among them: the Anne of Green Gables books and the Betsy-Tacy-Tib books, because they allowed me to experience other girls’ coming-of-age stories as unfolding slowly over time, rather than rapidly within the space of a single novel; and The Chronicles of Narnia, because I really really needed a world of more possibilities than the ones I saw around me in the Tennessee of the 1970s and ’80s.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I used to reread a ton! All the books and series mentioned above I’ve read probably four or five times (or more). Some more mature novels that I’ve read and returned to just for the joy of it include: Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë; Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen; Bleak House, Charles Dickens; Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston; many of Octavia Butler’s novels, and Mama Day, Gloria Naylor. There are many more I’ve read multiple times because I was teaching or writing about them. In terms of poetry, I tend to read collections through once and then dig back into them for specific poems, rather than reread the collection from cover to cover (again, unless I’m teaching or writing about them). But some of the collections that I go back into often are: Blacks, Gwendolyn Brooks; Robert Hayden’s Collected Poems; She Tries Her Tongue, Her Silence Softly Breaks, M. NourbeSe Philip; Does Your House Have Lions?, Sonia Sanchez; Blessing the Boats, Lucille Clifton; Sleeping with the Dictionary, Harryette Mullen; The Phoenix Gone, The Terrace Empty (and now Portrait of the Self as Nation), Marilyn Chin; Bright Existence, Brenda Hillman; Piece Logic, Erica Hunt; City Eclogue, Ed Roberson; Texture Notes, Sawako Nakayasu; Calamities, Renee Gladman; Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, Ross Gay; Engine Empire, Cathy Park Hong; and The Blue Clerk, Dionne Brand. But this is in many ways misleading, because I tend to reread poets—throughout their oeuvres—rather than specific collections. I have many strong favorites whose work I love across several books without the book being the key to what I love. (I was about to start naming my poet-loves, but that’s really not what the questions was—and besides, the list would just be overwhelming. We live in an amazing time for poetry!)

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

It’s probably Naylor’s Mama Day, which I think of as the African American love story par excellence, and which calls forth all three of those reactions from me in spades, every time I read it. But truth be told, I laugh and cry my way through most good works of fiction and poetry—laughing out loud and crying real tears. People sitting near me on planes and subways must think I’m bizarre.

How do you decide what to read next?

Several ways (in no particular order): I go to readings and buy the books of the poets & other writers who move me; I used to catch announcements of new books on Twitter, though I’m moving away from that app; I listen to literary podcasts (NY Times Book Review, Between the Covers, Well-Read Black Girl, VS, New Books Network); I have many friends who are big readers and who keep me up on what they’ve loved; I get requests to blurb books, which I’m occasionally able to do; I’m on a bunch of publishers’ mailing lists and receive announcements of new releases; I browse actual bookstore shelves at my favorite local indie bookstores (WORD Books, McNally Jackson, The Strand); and I impulse-buy at airport bookstores when I find myself with a flight that I don’t have to work through. Also, as I increasingly end up buying & receiving way more books than I have time to read these days, I browse my own bookshelves for the books I was excited to read but haven’t gotten around to. Basically, I surround myself with books and access to books, and then I reach for whatever my mood or preoccupations call for at the time.

Brandon Som, author of Tripas

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I used to love writing at night. As an undergraduate student, I had a professor who also wrote late into the night. He told me the reason why it’s good to write at night is because at that time everyone else is dreaming. I imagined writers at night picking up the signals of collective dreaming like radio antennae. Of course, not everyone is sleeping at that time. At the center of my book Tripas is my grandmother, who for years worked third shift at Motorola. I later learned to love writing in the morning with coffee and after a night’s sleep had cleared my mind’s desktop and when things seemed fresh and still possible. I have a two-year old now and nights and mornings are often devoted to caring for him—devoted to the routines for sleep or getting off to preschool. I’m trying to write whenever and for however long I can within small moments during the day—carrying materials with me always and trying to turn on like a faucet or light switch.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

“Tackle” and “block” here remind me of contact sports, that writing is physical and that if I let myself I can waste a lot of time and do significant damage beating myself up at the writing desk. I’m trying to be kinder and gentler with my writing practice. I’ve come to see my writing process as a diverse or varied series of practices. I try to be honest and generous with what I can do at any given writing session. Maybe today I focus on describing a family photograph, or engaging some visual art. Maybe today I’m only writing a list of objects for a scene I want to develop. I’m rarely telling myself that I’m sitting down to write a poem. Writer’s block is for sure to happen if I do. Instead, I work with small tasks, small to-dos. Then I assemble the parts and tinker with the gears and levers.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I cannot imagine my life without any of these, and they each inform, influence, and make their way into my poems. Poetry is hungry for content and form across media and disciplines. I’m trying to make my poetry practice permeable to and inclusive of all that I’m consuming, all that I’m bingeing.

How do you decide what to read next?

I didn’t read books growing up, so I started my reading life late. I’m also a first generation college student and have the experience of feeling like everyone around me has read more, feeling like I’m trying to catch up on the assigned reading of some syllabus I didn’t get on the first day of class. So I’m always keeping book lists and creating reminder-remainder stacks of books on my nightstand or dresser. Often my students or colleagues reference something or suggest something that I should have read but haven’t yet. In books I love, I like to comb through the acknowledgments page to find a writer’s community. With writers I love, I often want to read their friends, immerse myself in their correspondences.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

Just one is too hard, so I’m going to cheat and share two. I wish I would have read Frances Chung’s Crazy Melon, a book of prose and verse with an opening line that begins “Yo vivo en barrio chino.” That interlingual and intercultural claiming of self and place is richly complex and deeply inspiring to me now and could have helped out (and knocked out) my younger poet-self. I’d also say Juan Felipe Herrera’s Notebooks of a Chile Verde Smuggler, an extraordinary pillow book of chisme and poetics that includes a list of Chicano word-inventions that you can’t Google but that I recently shared with my nana, who proceeded to crack each word open like cascarones breaking over us with the confetti of collective history, grief, and giggles.

Monica Youn, author of From From

Who do you most wish would read your book?

I thought of this book as my contribution to an ongoing conversation: communities have been learning each others’ often-suppressed or ignored histories and have been searching for new strategies for solidarity and resistance. So although a primary audience for my book have been members of the Asian American diaspora—especially those who feel disconnected from a sense of “authentic” connection to their Asian heritage—I have felt the most grateful for the generous and thoughtful responses I’ve heard from the Black and Brown communities, and I look forward to continuing these conversations as I keep learning, growing, and working as a poet and as a person.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I try hard not to obsess about subject matter. I feel like the model of the poetic “muse”—some sort of subject-matter fairy appearing from on high and smashing writers block with a magic wand—is the least helpful model of artistic process imaginable. Every poetic subject contains an infinitude of possibilities—if you were sufficiently inspired to write one poem, chances are that further exploration would uncover new angles and aspects that you weren’t able to cover in a single take. I also find that a “multiple take” approach helps me to do justice to “difficult” or complex topics—the possibility of being able to balance out a particularly adventurous take with another perspective enables me to take the risks necessary to a more holistic view of the topic. So I’ll often make return journeys to the territories I visited in previous poems, always looking for new opportunities for adventure.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

In recent poems, including those in this book, I’ve been making an effort not to know where the poem will go after the opening few lines. I feel like this non-teleological approach lets me explore new avenues whose entrances might not have been visible when I started out on the poem, without rushing along the way to a predetermined destination. It allows me a more immediate and, I think, a deeper engagement with the subject matter—you can never really get to know a place without allowing yourself to get thoroughly lost in it.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

It’s hard for me to imagine my life as a writer without my usual practice of visiting galleries and museums to experience visual art. I like that visual art allows a more open approach to duration and perspective than more sequential art forms permit, and since I have little background in visual art, the learning curve remains satisfyingly steep for me. I find that a visual artwork can occupy a different part of my brain than that which has already been coded with the linguistic or the linear – it sits in the same part of my consciousness where dreams live, which is particularly helpful for me since I rarely remember my dreams.

How do you decide what to read next?

I’m one of these people who will always have multiple books open on my desk that I return to as the mood strikes me. I try to have an ongoing reading list based on my current project, but also to stay open to things I discover on a daily basis. I also have different types of reading that I allow myself—desktop books for the workday, audiobooks and podcasts for walking and driving, and nightstand books for bedtime.

•

TRANSLATED LITERATURE

Bora Chung, author of Cursed Bunny

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I hope people don’t find this disgusting: I trim my fingernails before I start typing. I used to learn martial arts and my teachers all advised me to keep my fingernails short. The reason was because if your fingernails are long, you could end up ruining expensive gear (kendo gloves can cost a fortune), hurting yourself (especially the palm when making a fist), or scratching your opponent, which was a very big no-no. Over the years I learned to enjoy the sensation of my fingertips touching the keyboard or squeezing the pen. I quit martial arts long ago but still keep my fingernails very short.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

I love horror movies and absolutely cannot live without them. Doesn’t matter which genre—ghost stories, slasher films with serial killers, zombies or aliens—I devour them all. Fear of death is universal but perhaps that is why it is so difficult to build a good horror story with something fresh and creepy.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

I do the dishes. When there are no dishes to be done, I do the laundry. If there’s no dirty laundry, I vacuum the apartment. And then I feel like I’ve done so much work for the day and don’t feel guilty about taking a nap. I may have not written a single word but at least the house looks spotless, my dishes are shining and all the clothes are clean.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

I Burn Paris (Palę Paryż, 1923) by the Polish author Bruno Jasieński. As the title says, the novel is set in Paris and there is one chapter that describes a family drama between two brothers who are from Russia. The older one is a White officer in charge of the situation and the younger brother is a Communist dying of a fictional plague. The White officer doesn’t recognize his brother at first and asks his name and rank, only to find out that the dying “enemy” before him is his long-lost sibling. The depiction of love, despair, pain and loss rips my heart every time. And the author’s own life story is perhaps even more dramatic than his works.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Teach language and literature. I used to be a teacher for more than a decade and if you count my days as an assistant instructor (that’s what they called the job at IU) I taught for almost 20 years. I thoroughly loved the job. I was a good teacher because I believed in knowledge and education. It seems that now my life picked a different path for me so I won’t be going back to teaching at least for the foreseeable future. But the faith is still there.

Anton Hur, translator of Cursed Bunny

Who do you most wish would read this book?

Men, because men are trash. Yes, all men. Trash. Patriarchy is an airborne disease that infects everyone. As a man, you don’t even need to consciously buy into patriarchy, you’re still benefiting from it at some non-man’s expense. You can be the most woke feminist man in the world, it doesn’t matter—patriarchy will make you trash. As a cisgender man, I do not want to be trash, which is why the patriarchy must be dismantled, and for that to happen, men need to make a concerted effort to learn, to feel, and to think about misogyny, homophobia, and transphobia. Books like Cursed Bunny will help, plus, it’s fun to read! There’s a talking head in a toilet! Can’t beat that.

What time of day do you work (and why)?

I am a night owl but due to the fact that I am interested in keeping my marriage intact, I have been forcing myself to work during daylight hours for the past ten years that I have been together with my husband. Before I met him, I would work all night and submit at dawn and sleep through the morning. I was gaslit throughout my childhood by parents and teachers into thinking this was not a “normal” way to live a life and my health would deteriorate, but then I found out about Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome. To this day, I have trouble keeping 100% conscious in the hours between 1 pm and 7 pm—I feel jetlagged and it’s torture to stay awake—but on the other hand, my husband is very good-looking.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

There is kind of a thing translators have where we’re not translating as swiftly as we normally are, and I think this has to do with not having found the right voice or rhythm to translate in yet. This usually happens in the beginning of a project where you have to teach yourself how to translate something or you’re coming off a project that has a different voice. For example, I was coming off of Blood of the Old Kings by Kim Sung-il when I dove into Beyond the Story: 10-Year Record of BTS, so I had to go from high-register high-fantasy to contemporary music journalism overnight. When you’ve been producing 80,000 words in one voice and have to switch to a completely different voice right away, you’re going to be a bit blocked. You just have to be very quiet and listen very carefully to the source text until the voice comes to you. It’s trying to find you!

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

I recently sold my first novel to HarperVia and it’s coming out in July 2024, and I was able to write it based on the advice of the Korean poet Lee Seong-bok in his book Indeterminate Inflorescence, which I translated into English and published through Sublunary Editions. It’s a series of aphorisms taken from his poetics lectures. This book changed my life. Here’s aphorism 178: “Write in one sprint. Once thinking begins to intervene, time and place scatter, and the flow of action is interrupted. Think when you’re not writing, don’t think at all when you’re writing. But we always end up doing the opposite.” Not only are the aphorisms inspiring advice, they are pure poetry.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

My parents had the most significant impact on my literary education by preventing me from receiving a literary education when I most wanted to have one. They gave me an ultimatum. Either I study law or medicine or I do not go to college at all. Because I loved books, I wanted to go to college, even if it meant studying something I didn’t want to study. I picked law because it looked easier. It was such a weird experience because I ended up at a Korean university that did not allow you to change majors and I ended up with a full ride the whole way, so I was free to ignore my parents—I practically disowned them throughout my 20s and allowed them back in my life only in my 30s—but I could do nothing about my major without losing my scholarship. I hated my parents more than I hated law, so I stuck with law, delaying my formal literary education into my 30s.

David Diop, author of Beyond the Door of No Return

Answers translated by Ian Van Wye

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best advice I’ve ever been given came from my father, who sadly passed away a few months ago: “Never give up, persevere on your chosen path. To exist is to insist.”

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

It was my mother who inspired me to write. As a child, I would always see her with a pen in one hand and a book in the other. To this day she remains passionate about literature and philosophy.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I write my novels with a pen, in notebooks with black or blue leather covers. Then I type out what I’ve written before sending it to my editor. Even though I draft my academic books on a computer, I realized that for my works of fiction, I had to return to the almost primordial act of writing by hand—what I learned to do with a pen and paper growing up in Senegal. It’s in this way that I manage to make what I write conform as exactly as possible to the images I have in my head.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

Homer’s Iliad. I was twelve years old, I believe. All of a sudden I began to understand that men and women, whenever or wherever they lived, were haunted by the same questions of love, friendship, war, and death. I think I realized then for the first time that some of the greatest lessons about life are found in reading and literature.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Black Boy by Richard Wright. A book that recounts the painful birth of a great writer. Despite the insurmountable obstacles Wright describes, I began to understand how there was nothing, ultimately, that could entirely thwart him in his journey toward writing. The book is nothing short of an ode to liberty.

Sam Taylor, translator of Beyond the Door of No Return

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t suffer from writer’s block in the traditional sense of lacking inspiration, but I do sometimes feel like I have to scale a wall of dread before I start. I tend to get over this by running or cycling or meditating and letting my subconscious loose on the next scene. Once I’ve got the first line, the rest of it usually falls into place. I don’t think I’ve ever had translator’s block.

What was the first book you fell in love with (and why)?

The Lord of the Rings. I was ill in bed, aged about eleven, when I first read it, and it… transported me.

Which book(s) do you reread?

The one I’ve reread the most, other than children’s books, is Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. I quite often pick it up, thinking I’ll just read a few lines, and end up being sucked into the story again.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Answering interview questions. Or lying in a hammock and reading.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

The one that comes to mind is something I read recently: A Terrible Kindness by Jo Browning Wroe. It first made me cry about twenty pages in, which is just ridiculous. When I came to the final part of the story, I went up to my bedroom to finish it because I knew it was going to make me sob my heart out and I didn’t want to alarm my family.

Stênio Gardel, author of The Words That Remain

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best writing advice was given to me by author, teacher and friend Socorro Acioli: tell the stories only you can tell. It helped me stop comparing my writing to other people’s work as well as made me more clearly understand how my life and experiences play such a pivotal role in the stories I want to write.

What part of your writing or translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

Maybe the fact that I don’t write each day. It’s quite common to hear that it is mandatory to write something every single day if you really want to become a writer or an author. It might work for some people and that’s great, but I believe each one can find their own process in a free and honest way. Before I started The Words That Remain, I outlined the entire story first, thought carefully about every event I’d choose to tell in Raimundo’s story. That part of imagining is very important for me and most of it happens away from the blank page. Only after I started putting down the words did I push myself to work every day until the book was finished.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

One of my earliest literary influences is The Hound of the Baskervilles, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. I was amazed and scared sometimes by the suspenseful atmosphere and intrigued by Sherlock Holmes’ methodic intelligence. I was beyond surprised to feel that way, becoming so involved and engaged in the story. Today I am sure that reading Doyle’s novel was largely responsible for my dream to pursue writing. I believe it was back then that I realized what books could do and that I wanted to invent stories that would reach and move people.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I try to read Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner every year.

How do you decide what to read next?

One thing I try to do is find a balance between classic and contemporary literature, which is not always easy, because there is so much wonderful new literature nowadays, but at the same time I still have a lot of classic authors to keep up with.

Bruna Dantas Lobato, translator of The Words That Remain

What time of day do you work (and why)?

I’ve tried to be a morning person, or even a daytime person, but the truth is that I only start to come alive at around 10 pm. Blame it on my delayed sleep phase syndrome. My best fiction and translation writing happens after 2 am, when I’m all alone and I have no other commitments, not even mealtimes to break up my day. My schedule feels wide open and all my own. I’m always surprised when the sun comes up that so much time has gone by without my noticing. That’s usually my cue to eat breakfast and go to bed.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

I go out on a walk, grab coffee with a friend, watch a movie, read for pleasure. I rest, which can be hard to do sometimes, with all my book projects and deadlines. But I’ve learned that the less time I have for it, the more I need it. After some time away from the page, I’ll spontaneously have the urge to get back to it again. A line or image will sneak up on me and I won’t even remember what was keeping me from writing.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Years ago I heard Jamaica Kincaid say at a talk that she wouldn’t respect any writer who merely wanted to please, and I love that as a guiding principle for my work. The worst advice I’ve ever received, when I was still too young to know better, was the opposite of that: that I needed to keep my white American reader in mind, someone who knows little about people like me, who expects people like me to perform in certain ways for their benefit, who would love for me to write a version of Brazil that echoes their vision. Hearing Kincaid speak, and reading her books in college, disabused me of that notion. Writing and translating to please had always felt unnatural to me, and difficult for all the wrong reasons. I’d much prefer to surprise, delight, move, question. Even better if I manage to surprise, delight, move, and question myself.

What part of your writing or translating routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I did a DIY residency at a religious hermitage a couple of years ago and got into the habit of burning a votive candle while I write. Now I light one every time I want focused creative time, usually late at night, with a hot cup of tea. It helps me focus and stay away from distractions, like a slower Pomodoro timer of sorts. It feels sacrilegious to reply to emails or go on social media while the wax is melting. I also like that I can stare at the flame when the writing gets hard. It’s much more soothing than the blank page.

Which book(s) do you reread?

I’m constantly looking for a great party scene, or a lovely description of a cake, or that bit of dialogue that sounds just right and will help me with my current project. I keep my favorites on a shelf next to my desk for reference and full rereads: books by Jean Rhys, Jamaica Kincaid, Italo Calvino, James Baldwin, Grace Paley, Clarice Lispector, Tove Ditlevsen, W.G. Sebald, Banana Yoshimoto, Tove Jansson, Marie NDiaye, Denis Johnson, Anne Carson, Amy Hempel, Deborah Levy, Ayşegül Savaş, and Sigrid Nunez. I just finished rereading Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book, translated by Thomas Teal, for what must have been the fifth time. I can’t get over how she centers dozens of episodic chapters around only two characters and manages to sustain the whole novel that way. It’s taught me a lot about structuring the subtle drama and absurdity of daily life, and how much you can accomplish with just two characters talking.

Pilar Quintana, author of Abyss

What time of day do you work (and why)?

I work from 9 or 10 am, after my kid goes to school, to 2 or 3 pm, to go running and get ready for when he’s back. My kid’s school is my room of one’s own.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

I don’t write unless I know what I’m writing about. So, lots of planning beforehand.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best advice I received was to never fall in love with what I write to the extent that I cannot see if it’s not good enough. The second best was to throw away what is not good enough.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

After I graduated from university, writing for TV plays was very important. It taught me to write stories in an effective way.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

Crónica de una muerte anunciada [Chronicle of a Death Foretold], by Gabriel García Márquez. I had to read it again as soon as I finished it the first time, and then again and again, obsessively. It made me want to become a writer. I wanted to do just that, to write a compelling story that would one day obsess someone.

Which book(s) do you reread?

There are two: Ficciones [Fictions] and El Aleph [The Aleph], by Jorge Luis Borges. I don’t reread them whole at once but go back once and again to the short stories in them.

Lisa Dillman, translator of Abyss

What time of day do you work (and why)?

I like to work early, and ideally after swimming, which makes my brain feels fresh. On days when I’m not teaching, I sometimes get up at 5.00, go swim, and then park myself at a café with my decaf and my bagel. I have some regular spots where they don’t care how long I hang out, and I can easily sit there translating for four hours. It also helps greatly _not_ to check my email first.

How do you tackle writer’s (or translator’s!) block?

One of the most wonderful things about translation is that, by default, there is no writer’s block! You have the materia prima there before you. But at times when the creative juices are not flowing the way I need them to for tricky passages, neologisms, delicate voices and all other manner of challenges, I usually edit, reread what I translated the day before, and reread the passages to come.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your literary education?

My mother, without question. She is the most voracious reader I know and smart as a whip, and she instilled the love of literature in me from a very young age. My mom still probably reads two books a week. We talk almost every day and I love hearing which books she’s got out from the library at any given moment (shoutout to the Los Angeles County Library system).

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be working?

Hey, I wonder what the dog is doing?

If you weren’t a translator, what would you do instead?

Are we talking dream world, here? If so, I’d be a singer. Both of my parents sang, my mother is still in a choir. I can’t sing to save my life and it strikes me as one of the most beautiful talents in the world.

Astrid Roemer, author of On a Woman’s Madness

Translated from the Dutch by Lucy Scott

Who do you most wish would read this book?

People with hate in their heads for lifestyles they do not prefer.

What time of day do you work (and why)?

In the tropics. Early mornings and early evenings. Because of the temperature.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Love songs. Bach.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

Alice in Wonderland.

What do you always want to talk about in interviews but never get to?

How I have been stalked for years…

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Cosmologist.

•

YOUNG PEOPLE’S LITERATURE

Kenneth M. Cadow, author of Gather

Who do you most wish would read your book and why?

I wrote this book for rural kids, and I hope they read it because the perspective in it—Ian’s—may help them realize that the lives they live are worth reading and writing about. For crossover readers—particularly adults who aspire to educational or social services careers—I hope they can get a sense of what they’ll be up against, and that what they’re up against can be beautiful if they’re willing to buck the system a little. Finally, I hope that urban students read Gather. Edward, Ian’s classmate in the book, is one such person. Perhaps if Edward had found this book before being transplanted from the city to the country, he wouldn’t have sat behind his desk and judged this rural community with such unfortunate self-confidence. Our country is in dire need of building understanding and empathy between the 80-percent metro and the 20-percent rural people who comprise our population and our democracy.

What time of day do you write (and why)?

I am quoting Virginia Euwer Wolff, a friend and mentor: “I get up at least two hours before my inner critic.” I’m not self-conscious very early in the morning and the analytic part of my brain is on a different sleep schedule. For the first ten minutes or so, I read what I’ve already written. This helps with consistency of voice and reenforces the set of eyes I’m behind in telling story. But I don’t correct anything. Then I write for a couple hours, hardly ever hitting the backspace button or crossing stuff out. As the sun gets higher, I become more aware of myself and my opinions, confusions, and dubiousities. By afternoon my head is pretty much a traffic jam, so my time is better spent taking a walk with my wife and our dog. Before I get to that point, though, I go through and tidy things up. My writing schedule is limited to weekends and holidays because of my day job.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

It’s extremely rare for me to make any changes without reading my work aloud to myself, and I built my tiny cabin—96 square feet and awkward to get to—for this express purpose. I don’t know if that’s all that surprising… maybe it’s more surprising that I pretty much constantly nibble like a rodent while I’m writing. I start the morning with a home-baked cookie, preferably chocolate chip. This lasts me about an hour. As the morning goes on, I switch to fruit and then graduate to more savory foods like pretzels and hummus or cheddar cheese and crackers. I shift to water instead of coffee. If I’ve written a powerful passage, I step outside and bang my head against a tree.

How do you decide what to read next?

A lot of what I read is driven by what I’m writing and where I am in the process. I love character-driven novels, but if my own characters are still forming, they’re too inclined to be influenced by characters in whatever book I go to sleep with (I mean…. can you imagine if Eleanor Porter had been reading The Catcher in the Rye when she wrote Pollyanna? I kind of wish she had been, if chronology made that possible). In the early stages of my writing, I tend toward creative nonfiction such as Winterworld: The Ingenuity of Animal Survival by Bernd Heinrich, for example. But when my characters are strong enough to hold their own, I ask my wife, Lisa, for fiction recommendations. Matching readers with the right book is a profound gift, and she has it.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

I would be a hemmer and a haw-er. As it stands, I get to do a lot of this in my day job as a public high school principal in rural Vermont. I’m often at a loss for words because the systems to which leaders are held accountable seem awfully out of touch with the needs and visions and passions of the folks they were originally intended to serve. When I feel this way, I focus on listening locally and doing what I can to foster the successes that make teaching, learning, working, and living around these parts more genuinely satisfying.

Huda Fahmy, author of Huda F Cares?

How do you tackle writer’s block?

How I tackle writer’s block: I step away from the work and all the expectations that come with it. I go for a walk, spend time with my family, call my mom and sisters, read other books that are in the same genre, and look at old photographs from when I was younger to see if I could remember what I was going through when the picture was taken.

Which book(s) do you reread?

Books I reread include the Quran, Calvin and Hobbes, The Protector of the Small series, The Princess Bride, and so many romance novels.

What’s one book you wish you had read when you were young?

One book I wish I’d read when I was younger is S.K. Ali’s Love from A to Z.

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

The best writing advice I’d ever gotten was to only take criticism from people I would go to for advice.

What time of day do you write (and why)?

The time of day I write is largely decided by my children’s school schedule. When they come home, I like to put away my work and spend as much time making them giggle and laugh as possible. So I write between 8:30 and 2:30 with about an hour for lunch.

Katherine Marsh, author of The Lost Year: A Survival Story of the Ukrainian Famine

Who do you most wish would read your book?

I wish my late grandma, Natalia, could read The Lost Year because the stories she told me about her childhood in Ukraine and the family she left behind helped inspire the book. She was not much of a reader because she only had a fourth-grade education. But she was a marvelous storyteller and would have been deeply touched that I chose to write a story about the love, loss, and longing she felt for her family and homeland.

Who is the person, or what is the place or practice that had the most significant impact on your writing education?

In my 20s and early 30s, I worked as a long-form narrative journalist, first as a reporter, then as an editor. Journalism taught me so much about how to write fiction including how to tell a story in a way that engages the reader and how to use reporting and observational detail to bring characters and situations to life. I also learned a lot about the craft of writing, including the importance of revision.

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

The part where I throw myself down on the couch and cry. I’m only half joking! Every book I write I hit at least one, and often multiple, snags and become convinced that I can’t write at all. This despair can last for weeks. But eight books in, I know this, too, is part of my “routine” and that I will eventually snap out of it, reconnect, and find a solution. This is why I always tell kids that they shouldn’t think in terms of being “good” or “bad” writers. Like Matthew’s dad tells him in The Lost Year, “It’s the caring part that makes you a writer—not being ‘good’ at it.”

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

I cannot read Charlotte’s Web without weeping. It’s impossible. I’ve read it many times, including to my own kids, and I choke up every time. My husband is from Maine, where the story is set, and I dream of buying a farm there someday for all our animals. We already have seven chickens, two cats, a bunny and an axolotl and I’d love nothing more than to add a pig named Wilbur and invite the Charlottes of the world into the barn.

How do you decide what to read next?

I usually read several books at once—one is a read-aloud to one or the other of my kids, usually a book for young people they wouldn’t read on their own but we both might like. For the past fifteen years, I’ve belonged to a great book club of female journalists, many of whom have reported from or still report about Ukraine and Russia. We all take turns selecting books, primarily adult literary fiction. Finally, I follow my curiosity, like right now, one of the books I’m reading is David Copperfield by Charles Dickens to see how Barbara Kingsolver adapted it to write another book I enjoyed this year, Demon Copperhead.

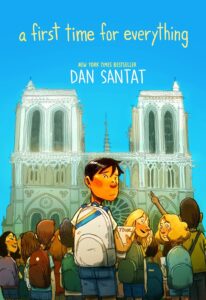

Dan Santat, author of A First Time for Everything

What part of your writing routine do you think would surprise your readers?

I run a lot, and while I’m running I’ll think about a little segment of a story I’m working on. I do this for a few reasons. First, it keeps my mind out of the moment of actually running and sometimes the best solutions to a story come from just letting your mind wander and think of absurd things. Second, the running wakes my mind up and clears my mind.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

There’s so much about popular culture that I’m grateful for and to single out one thing is impossible for me to do, but if I had to choose one it really was movies which taught me how to love storytelling. I can’t play a bad video game or listen to a bad song, but for some reason I can watch a bad movie and study it and ask myself why I think it’s bad while some other person might possibly love it. I watch movies in a pursuit to make me laugh, cry, or even leave me confused with its experimentation. Animated, dramas, action, or low budget independent horror. Ultimately, I just want to feel an emotion and movies always deliver.

What was the first book you fell in love with (why)?

Danny and the Dinosaur by Syd Hoff. It was the very first book I ever learned to read. I remember my mother would read the book to me hundreds of times and then one day there was a moment I stared at the words on the page and it all suddenly just made sense. I immediately picked up other books on my bookshelf and realized I could read. Danny and the Dinosaur holds a special place in my heart and that’s why it’s my most loved book.

What is your favorite way to procrastinate when you are meant to be writing?

I can easily get sucked into a video game, especially video games with a compelling story. Sometimes I can get so intensely addicted to a game that the only way to break away from it is to binge the game and complete it in its entirety in order for the urge to play goes away.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you (made you laugh, cry, be angry)?

Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris. I never laughed so hard at a book. It’s my personal favorite book of all time.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

Well I spend a good amount of time in my career as an illustrator for other authors. I’ve illustrated well over a hundred books for other authors so I assume I would do that. I also feel like I’m cheating by giving you an answer like that so the other answers would be a dentist (because I almost became a dentist) or I’d be a coffee roaster or make furniture, both of which are hobbies of mine.