What Vera Mutafchieva’s The Case of Cem Tells Us About Europe’s Past and Present

Angela Rodel on Translating a 20th-Century Bulgarian Classic

What first drew me to Bulgaria was not the literature, but the music: the brassy female voices, the funky lopsided rhythms, the squealing bagpipes. The Mystere les Voix Bulgares sounded like a choir of (albeit deafening) angels when I first heard them as an undergrad at Yale. When I finally got over to Sofia in the mid-1990s to follow these sounds to their source, it’s not surprising I ended up marrying a Bulgarian musician.

But luckily this particular wooden flute player was also a poet who introduced me to another divine chorus of Bulgarian voices: the vibrant, turn-of-the-millennium literary scene. Poetry was the dominant genre at the time, and the explosion of post-socialist literary experimentation found its expression in avant-garde performances.

Yet as a reader I have always been a fan of novels—the fatter and more historical, the better. My idea of a perfect afternoon is to curl up with a tome of Iris Murdoch, Robertson Davies, or Dostoevsky. I asked my then-husband for recommendations of classic Bulgarian novels. He thought for a moment, then said: The Case of Cem. I was stunned by what I found in this historical novel published in 1967 at the height of the Cold War by the prominent Ottomanist, Vera Mutafchieva.

In addition to the big historical questions about individual agency that it raises, The Case of Cem is also a very personal exploration of emigration and loss.On the surface, The Case of Cem tells a straightforward tale: upon the death of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror in 1481, his eldest son Bayezid takes the throne. However, discontented factions within the Ottoman army urge Mehmed’s second son Cem, a well-educated and experienced soldier, to oppose his brother’s ascension and to suggest the two split the empire. Bayezid refuses, setting off a ruthless power struggle.

Cem is forced into long years of exile and finds himself essentially a hostage, a pawn for European powers as they try to slow the Ottoman Empire’s expansion and even to take back Constantinople. Cem wanders from Syria, Egypt, and Rhodes to Rome, where he is held by Pope Innocent VIII, before finally being passed on King Charles VIII of France. Cem dies in Neapoli in 1495 under mysterious circumstances, but even death is no end to exile: several more years pass before his body arrives back home to its final resting place.

But the book’s structure is anything but straightforward: Mutafchieva presents the story as a series of depositions by historical figures before a court, bringing medieval history and modern “courtroom drama” together in a way that is extremely experimental for Bulgarian (and I daresay world) literature of the time. In The Case of Cem, we hear firsthand from Mehmed’s grand vizier, Pierre d’Aubusson (grand master of the knights of Rhodes), and many others.

Yet the one character who never speaks directly to the court is Cem himself; he remains silent, not unlike the Balkans themselves, who were often voiceless victims in the tug-of-war between East and West. The closest we get to Cem is through the Persian poet Saadi, Cem’s companion and (as becomes clear as the novel progresses) erstwhile lover. Saadi is hands-down the most sympathetic character in the book—the greedy, ever-scheming Westerners look quite craven by comparison—leading me to wonder how Mutafchieva managed to get such positive queer representation past the communist censors of that era. Perhaps because Saadi was Persian and not Bulgarian?

Although Cem’s story is intriguing, fit for a History Channel special, why should Cold War-era Bulgarians or contemporary readers of English care about the fate of a medieval Ottoman prince? In the foreword to the novel, the author herself raises this question, and uses her insight as a historian to offer a convincing answer: “What brings us back to Cem today? In the Cem affair, over a whole decade and a half at the tail end of the 15th century, the politics of the East and West were sketched out utterly clearly, with naked simplicity. Later they would call this ‘the beginning of the Eastern Question’ and they might be right.”

In addition to the big historical questions about individual agency that it raises, The Case of Cem is also a very personal exploration of emigration and loss. More than one Bulgarian critic has pointed out that Mutafchieva wrote the novel about a young prince in exile only a few years after her own brother Boyan defected to France in 1963.

Under socialism, Bulgarian defectors were generally not allowed to return and had very little contact with relatives behind the Iron Curtain. Authorities often punished loved ones left behind by denying them jobs and educational opportunities, or forcing them to collaborate with the secret police (a trap Mutafchieva found herself in). Not unlike Cem, defectors were often used as pawns by competing governments in propaganda campaigns, and a few such as Georgi Markov, were even assassinated.

Some scholars see Mutafchieva’s The Case of Cem as a veiled critique or interrogation of Cold War East-West tensions and politics disguised in medieval trappings, which adds another layer of richness and relevancy—especially given the divide that remains even today within the European Union, as many eastern member-states such as Bulgaria continue to struggle with corruption, populism, weak democratic institutions, and a feeling of “second class citizenship” compared to wealthier western EU members.

Some scholars see Mutafchieva’s The Case of Cem as a veiled critique or interrogation of Cold War East-West tensions.The novel also put me, the translator from Bulgarian, on unfamiliar footing. Mutafchieva immediately throws the reader into Cem’s world, peppering the text with Turkisms she does not define or explain. Although Bulgarian language retains quite a few Turkish borrowings due to its 500 years in the Ottoman Empire, the author constantly uses terminology that is not familiar to the average Bulgarian reader. As a translator, I have tried preserve this aspect of Mutafchieva’s writings and leave many of the Turkish terms in, since they provide a strong sense of atmosphere, while the context generally makes clear what these unfamiliar words mean.

Although Mutafchieva was a highly respected historian, she clearly did not feel bound to one-hundred-percent historical accuracy in her fiction. She freely changes certain names and other historical details of the text; the first-person narrators are at times unreliable (if not downright deceptive), which adds another layer of complexity to their “testimony” before the court of history. Despite its historical grounding, at the end of the day, The Cem Affair is a work of fiction, and I respect and even marvel at the imaginative approach the otherwise fastidious Ottoman scholar Mutafchieva took in her tale of an exiled prince and his European wanderings.

Mutafchieva’s brilliant psychological portraits of these “witnesses of history,” especially the poet Saadi, pushed me to break one of my most ingrained translator’s habits I have faithfully stuck to for more than a decade: translating a book in order.

As I approached the end of the book, after nearly two hundred pages of being in Saadi’s head, following his thoughts, I couldn’t bear to let him go. I did not want to translate his final sections, so I jumped ahead out of order, and only when I had translated everything else I possibly could did I go back and finish Saadi.

Since I never had the honor of meeting Vera Mutafchieva before she passed away, I felt as if Saadi was my co-author of this translation, the co-creator I found myself in constant conversation with. The Persian poet is also a singer and musician, so perhaps it is not surprising that he drew me in, just as Bulgarian voices drew me into the wonderful world of translation so many years ago.

__________________________________

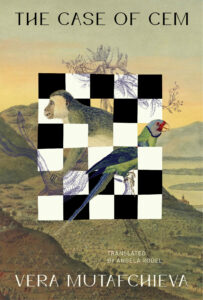

The Case of Cem by Vera Mutafchieva, translated by Angela Rodel, will be available from Sandorf Passage in 2024. Cover design by Dejana Pupovac.