John F. Kennedy’s Last Movie: From Russia with Love

“Kennedy proclaimed his love for James Bond whenever he could.”

John F. Kennedy’s voracious appetite for books was borne of long hospital stays in his youth (Colitis, Addison’s). By 1963, he’d been read the Last Rites many times (Catholic, Irish). He was 46; one doctor doubted he would make 31.

In the early days of their courtship Johnnie gifted future wife Jackie The Raven, a biography of Sam Houston and the story of the making of Texas; confirming his interest, he’d then given her Pilgrim’s Way, an embellished autobiography by John Buchan, the Scottish author-politician best known for his spy thrillers (The 39 Steps was adapted by Hitchcock), named for the Holy English road established by the assassination of the Martyred Saint, Thomas Becket. Pilgrim’s Way was the book Kennedy implored anyone who wished to understand him to read. It was referenced as one of the President’s favorite titles during National Library Week in 1963. Also listed was From Russia, with Love, published 1957, the fifth in writer Ian Fleming’s series of James Bond novels. ‘Understand me!’

Kennedy proclaimed his love for James Bond whenever he could. First, in a 1961 LIFE magazine feature at the height of his political popularity. At that time Bond was nationalist pulp for English public-school boys—he was practically invisible to America—and the President’s promotion led to Fleming’s first significant sales in the States. United Artists secured the film adaptation rights and rushed Dr. No into production owing, in no small part, to Kennedy’s adulation of the character.

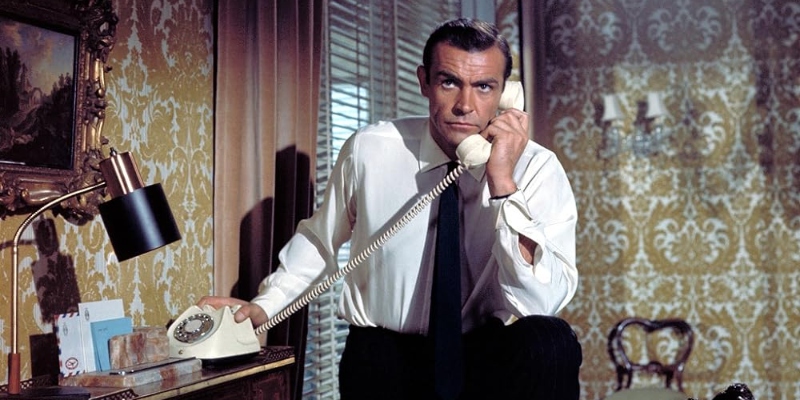

Kennedy tethered himself to Bond and, in particular, the Bond as embodied by Sean Connery, furnishing his own image with the character’s sharp shooting, snazzy dressing, brawny brainy sophisticate. The spy knew anyone ordering a glass of Chianti with a fillet of sole was a villain, and that every hot woman from Sunderland to Siberia would martyr themselves at his elm altar with a bent Hail Mary.

Though Fleming was at first distressed by the heft of Connery’s card-carrying SNP-member milkman taking the role of his “refined” (or never-worked-an-honest-day) murderous Tory James, he became so impressed by what the actor did for the character, that he built his Scottish heritage into subsequent books. United Artists’ movie adaptations leapt non-sequentially from Dr. No to From Russia with Love directed by JFK’s appreciation; Fleming ventriloquized his gratitude to the President for making him rich with Bond soppily pronouncing “We need more Kennedys’ in the series” next book, The Spy Who Loved Me (1962).

Fleming’s Spy was one of only three books in the possession of Lee Harvey Oswald at the time of his arrest: the others were Fleming’s Live and Let Die (Bond is sent from London to New York to investigate Mr. Big) and A Study of the USSR and Communism by Alfred Rieber and Robert Nelson. Lee actively sought out the books that Johnnie liked; though frequently accused of being thick, he too loved reading (especially the news), and even journaled an interest in short story writing, imagining a possible future for himself as a great literary documentarian of the contemporary American experience (which may have been a flicker of consideration as he crouched, cushioned and flanked by book-upon-book, tissue-paper-wrapped or spine turned inwards, in the room with the view on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository, from where the shots that killed the President were fired, be it the books written about him or the ones he’d write himself in prison).

The film adaptation of The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) was the last movie watched by Elvis Presley (unable to obtain a copy of his desired film, Star Wars), and Kennedy had a fan in Presley. The singer watched live on television as Lee Harvey Oswald was escorted towards a city-county jail transfer vehicle, and as Dallas strip-club owner Jack Ruby stepped out of the crowd to put a single, fatal bullet in his stomach. The medium’s first live homicide. Why? “I just had to show the world that a Jew has guts.” (The weirdo spent the previous night distributing free sandwiches and soft drinks to police station officers.) Elvis held court; responded; demanded from his friends there watching TV with him, be it Jack or be it Lee, that if he, the King, were to be dealt the same fate as the President, those present must promise to reach the assailant before the police. A bullet would be too easy. Gouge his fucking eyes out.

Between 1961 and 1963, President Kennedy watched 81 films at the White House cinema: mainly new releases, he broke in the auditorium with the John Huston and Arthur Miller collaboration, The Misfits, starring Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable as capturers of wild horses in their last earthly roles; 13 foreign-language productions followed (probably the dictate of Europhile Jackie) including Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (one of the few arty films Johnnie would tolerate), Francois Truffaut’s Jules et Jim, Ingmar Bergman’s The Devil’s Eye, the Friedrich Durrenmatt-penned noir It Happened In Broad Daylight, and Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (from which he walked after 20 minutes); 21 internationally produced movies (eight British, including Peter Sellers’ Mr. Topaze). During these two years, Hollywood studios were transitioning from black and white to color film, with stock historically expensive dramatically falling in price.

Color mattered: the advent and accessibility of television meant that film producers had to distinguish their product. At home, 97 percent of Americans were condemned to a black and white world. Color was the kino, and the pregnant journey to and fro.

The White House cinema was instituted by Franklin Roosevelt as a part of the President’s residential quarters (leading from the West to the East Wing; looking onto a grass flat that Hillary Clinton would spend her First Ladyship stewarding as a sculpture garden). Public knowledge of Presidential viewing habits are entirely credit to Paul Fischer (and backed up in some instances by the diaries of individual Presidents), the one and only White House projectionist from 1953— aged 25—until 1986, his retirement, spooling off titles picked by the three decades’ seven US Presidents.

Fischer had been a low-ranking Naval officer assigned to Harry Truman’s Presidential yacht until someone caught wind of his ability to project 35mm film. Subject to a security review, he was dispatched to Washington and ordered to project whatever and whenever for the then newly elected President Dwight Eisenhower (favorite movie: High Noon). Of his own accord, and to no particular end, Fischer kept meticulous records of the films he screened and the guests invited by the Presidents to watch them, which sat languishing as a stack of green ledgers in his home garage until the turn of the millennium, when a reporter, Irv Letofsky, showed up to prove or disprove their mythical reputation.

Kennedy tethered himself to Bond and, in particular, the Bond as embodied by Sean Connery.On November 11th in 1963, JFK saw The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T, an “American musical about a boy who dreams himself into a fantasy world ruled by a diabolical piano teacher.” A day earlier, on November 10th, he watched Nicholas Ray’s 55 Days at Peking, a historical epic about China’s Boxer Rebellion starring Charlton Heston and Ava Gardner (one of many starlets with whom he was linked romantically).

On November 13th, Johnnie had Greta Garbo over for dinner, gifting her an engraved whale tooth and imploring her to stay the night. Garbo made fast work of her calamares a la bruta and fled. She knew he had recently shagged her great rival, Marlene Dietrich (16 years between her and Johnnie, she was then 60 years old) and so had his father, Joseph (which Johnnie knew).

Prior to becoming a senator, Joseph had been a successful Hollywood producer. It was daddy that had made Johnnie a millionaire ten times over by the time he took office and paid the bribes and the propagandists to get him there. (Meanwhile around a quarter of US citizens earned less than $1500 annually.)

Joseph’s most coveted affair was with Gloria Swanson, today remembered for her late-career starring role in Sunset Boulevard. (Sunset is one of Donald Trump’s favorite films, and the most repeatedly screened during his tenure as 45th US President; Finding Dory was the first he watched in office.) The affair ended when Swanson discovered an expensive gift from Kennedy had been charged to her own account.

It was little wonder Johnnie and Joey had a complicated relationship with sex: when Johnnie aged 12 caught Joey and Gloria mid-coit on the deck of the yacht named after his mother, Joey simply laughed at him (and Johnnie, ‘crying, shaking,” unclear about exactly what daddy was doing, jumped overboard to swim to shore).

In the early days of Johnnie and Jackie, Joey steered his son’s girlfriend away from watching a Ronald Reagan film with the family, so that he could show her a room full of bound dolls, and boast to her about how much Gloria Swanson used to like to bonk with the toys looking on, describing with scientific scrutiny the character of her genitals.

Joseph by that time had made the equivalent of $85 million from his Hollywood investments (in a 1957 Fortune magazine article he was said to have a net worth of between $200–400 million), including profits from a “successful” plot to frame a rival cinema-chain owner for rape because he refused to sell to Kennedy something that wasn’t for sale. This afforded Johnnie and his siblings the ultra-rare privilege of their own home movie auditorium while growing up. Joey (laughing) groomed Johnnie for the country’s top role not through his experience in politics, but through the more mercenary practices of shooting film and making stars.

On the morning of November 16th, Johnnie travelled from Palm Beach, Florida, to NASA headquarters at Cape Canaveral (later renamed Cape Kennedy), where he hung out with Nazi rocket-man Werner von Braun. By the afternoon he was back in Palm Beach taking a swim, and later watched a game of football on TV. In the evening he serenaded his dinner guests with a “better than usual” rendition of his very favorite tune, “September Song” by Kurt Weill (former husband of Lotta Lenya who sang a great many of the songs originally composed for and with Bertolt Brecht, and who plays a sabre-toed Rosa Klebb in From Russia with Love).

On November 17th he watched Tony Richardson’s gadabout Tom Jones at a private screening in Palm Beach. By contrast with its source material, the film did very little: two earthquakes were blamed on the book’s publication in 1749. The film crystallized the 1960s before things really started swinging; giving permission for good guys to sleep about, and even making bad guys of those who didn’t.

Johnnie would have liked to recognize himself in the titular tom-cat, compensating for a sickly childhood by couching all he desired. True success meant the collapse of fantasy into reality through adventures in sex. The kino was foreplay for the forensic possibilities of real life; the depth and clarity that couldn’t be shown on screen (until his head was exploded and all the allusions that made art sacred and sex sexy were exploded with it).

Before Johnnie knew Marilyn, he had a poster of her upside down (legs akimbo), pinned to the rear of his hospital door as he recovered from back surgery in 1954. While Jackie complained about the poster, she unwittingly made the problem worse: delivering Johnnie his first encounter with James Bond in Fleming’s first book, Casino Royale. A fateful, toxic combination. Marilyn, Bond, James… back-brace, bang-bang, smokey-smoke, cortisone, methadone, codeine, change, Demerol, Ritalin, rights, power, powder, meprobamate… and librium, gamma… globulin… the President rose up. The poster was from Marilyn’s recent breakout role in Niagara, the Technicolor picture by Henry Hathaway that made her a star. It was from this film that Warhol stole the image basis for his infamous Marilyn silkscreens (awarding Jackie the same treatment in the immediate aftermath of Johnnie’s assassination); even Fleming references the image in From Russia, with Love, titling a chapter “The Mouth of Marilyn Monroe.”

A huge billboard promotes Niagara with Marilyn’s face; her mouth is a trap-hole a villain attempts to escape through, but who Bond and an ally have sights on. Tom Jones may have been John’s last movie (it was certainly Tony Richardson’s most successful: funds from which he’d use a couple of years later to support the prison break of Soviet spy, George Blake). There is only Fischer’s book-keeping to rely on, and there are errors: according to the projectionist’s notes he was showing films for the President’s delight all of one week after his death, on November 29th.

Fleming’s Spy was one of only three books in the possession of Lee Harvey Oswald at the time of his arrest.In the run up to the Texas trip, Kennedy had been on the campaign trail seeking to mend his fractured Democratic Party and win a second term as President. A brief stopover “home” at the Oval Office on November 20th (brother Robert’s birthday, for which a party was held where Gene Kelly and 60 others danced to the accordion) before jetting off to Texas on the morning of November 21st would have been an ideal opening to watch From Russia with Love.

Fischer records just one guest: Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., John’s special assistant and “court historian” (a screening of the Bond film organized by Schlesinger on the evening of November 21st when Kennedy was in Fort Worth is sometimes referenced; this may have happened, but it may also be misattributed given the chaos of the events that followed. This was the President’s home theater, after all). Kennedy would have viewed the movie propped up on pillows from an orthopaedic bed set up in the cinema to ease his chronic back pain. It would have been a touch after midnight and he probably enjoyed a doobie.

During the final two years of his life, regular meetings were had with painter Mary Pinchot Meyer—herself a target of assassination in 1964 (like Johnnie, shot in the back and the head)—who quoted the President’s limit of three spliffs in any one session. “No more! Suppose the Russians did something now.” She was also frequently seeing Timothy ‘hero of American consciousness’ Leary at this time. The guru would go on to credit Mary for influencing John’s views on nuclear disarmament (inferring their consumption of LSD).

With less familiar guests the President would sit centrestage in a rocking chair, soberly (painfully) smoking a cigar. Fischer fails to record “the bagman” as Johnnie’s guest, but wherever he went—to the pool of Palm Beach, to Wendy house Meyer or Wendy house Monroe—“the bagman” was ever present; closer and more constant even than Jackie, especially as the White House caravan hit the road.

The bagman’s job was straightforward. He carried a black, die cast metal suitcase, with a combination code lock (also known as “the black bag” and “the football”). All he had to do was carry that case, and remember the code to open it. Inside was the technology for a telephone line to the Prime Minister in the UK and the President of France, which could be hastily assembled anywhere with four minutes notice.

Also inside were a series of cryptic numbers: the codes to launch a full-scale nuclear attack, with a literal cartoon-comic book to demonstrate to the President and his aides in the simplest possible terms how many million human casualties they could expect from the degrees of assault they had to select from.

From Russia with Love had premiered in London that last October. Its adaptation from book to film replaced nemesis SMERSH, the Red Army’s real-life counter intelligence unit (which Bond destroys) with a Russian crime syndicate, lest a mistaken culture war activate the services of the bagman. The comma in the title was trashed. Otherwise, it’s a straight-up book-to-movie adaptation: lowest common denominator English spy-thriller fare of haughty cuisine; expensive smoking; stupid gadgets, car chases, “semi-rape” and the killing of foreigners and homosexuals.

Kennedy had already seen it once, able to obtain an advance copy screened at the White House on October 23rd in the company of his brother Robert, and Ben Bradlee (of the Washington Post, and Mary Meyer’s brother-in-law). “Kennedy seemed to enjoy the cool and the sex and the brutality,” Bradlee reported. “He seldom sat through an entire film, but he watched this one to the end.” Jackie held a dinner that same evening, and wore a dress given to her by the King of Jordan. Silk, sequins; as she delivered the roasties she imitated a belly dancer, and the group would have chuckled later in acknowledging the black mirror of the belly dancer in the movie’s opening sequence.

The only other films Kennedy is known to have watched twice while in office were the Guns of Navarone and West Side Story. When From Russia with Love released theatrically across the USA in May 1964, it was done with a savvy and macabre marketing ploy: distributor United Artists issued it as a double-bill with Burt Topper’s War is Hell, the film seen in-part by Lee Harvey Oswald as he hid at Dallas’ Texas Theatre, from where he was apprehended shortly after the shooting of the President (initially for the murder of a police officer, J.D. Tippit). This double was a neat riff on LHO’s brief abandon to Soviet Russia, and the heat of the Cold War.

As the open-topped motorcade passed the Texas Book Depository, and made its way along the grassy knoll of Dealey Plaza, Jackie said to JFK, “You certainly can’t say that the people of Dallas haven’t given you a nice welcome,” to which Johnnie responded (his last words), “No, you certainly can’t.” Bang (bang, bang [bang?]).

_____________________________

Excerpted from Stanley Schtinter’s Last Movies. Copyright © 2023 by Stanley Schtinter. Used with permission of the publisher, Tenement Press. All rights reserved.