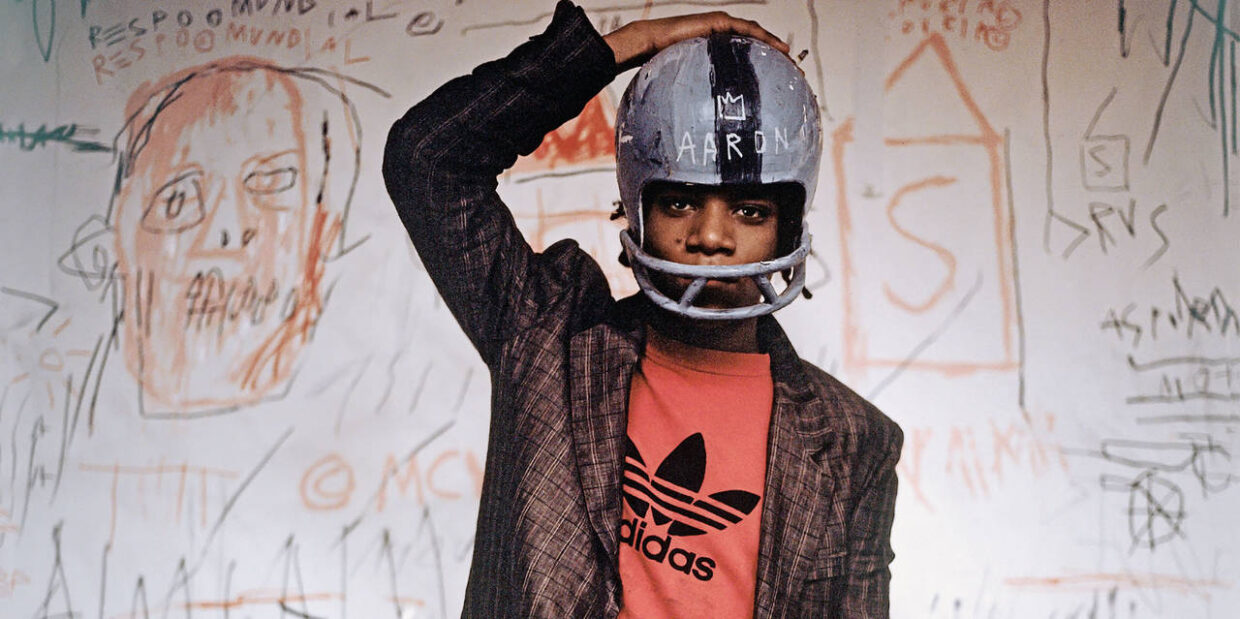

Graffiti Gentrification: Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore on the Exploitation of Basquiat

Considering Boom for Real: The Late-Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat While Walking Through Baltimore

Image courtesy Magnolia Pictures

Is the point of art to bring us into ourselves, or out? I mean the Parkway theater is my favorite place to go to get out of the heat—I can even stare at the high-concept magenta wallpaper in the bathrooms, digitized popcorn kernels “oating” by. Or notice the shining light outside as it settles over the decaying turn-of-the-century buildings across Charles Street, all those gorgeous reds and browns and look at those plants growing through the cracks in the bricks.

Usually when I go to an old theater I study the details, but with this theater you walk in and you just think: architect. Because the whole place has been gutted, and reimagined. Where did they get all this money?

Tonight I’m watching Boom for Real: The Late-Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat, which reveals nothing about Basquiat that wasn’t already part of the public record—he was brilliant and wild, charming and manipulative, seductive and ambitious—he was homeless as a teenager, he did a lot of drugs, he became the toast of the art world, he died way too young.

Everyone already knows the myth that Basquiat was a lone genius destroying convention to create his own form. Yes, he was driven to remake himself as a lone visionary in order to become a top-tier art-world commodity, and this actually happened, which is rare for anyone, especially a Black artist, but we already know this killed him, so why portray posthumous canonization as a glorious path? Unless the movie is just about making more money for the ghouls of the art world who have already made millions and millions from Basquiat’s death from an overdose at age twenty-seven.

I’m thinking about the Basquiat show I saw in Seattle in 1994, six years after his death—gazing at those paintings I felt an immediate sensory kinship with the dense layers of self-expression, the wildness, the raw beauty, the way language was interwoven with the visual, became the visual, until it was overcome by it. The movement, the free association that became a method and a system of organization, the disorientation that opens the mind.

I’m thinking about the Basquiat show I saw in Seattle in 1994, six years after his death—gazing at those paintings I felt an immediate sensory kinship with the dense layers of self-expression, the wildness, the raw beauty…The way we can create our own language, the symbols and the strength, the bending, the mesmerizing nurturing scream. I left that show wanting to create, knowing I could create, knowing. In the lobby of the Parkway Theatre there’s a flyer for a new building across from the train station that says:

THE ART OF BALTIMORE

NOW LEASING.

In the photo, it just looks like your average prefab yuppie loft to me, so I’m not sure where the art is, but I guess they mean this neighborhood, designated by the city as an ARTS DISTRICT to change blight into bright lights. The marketing of Baltimore as a creative hub—artists as tools for displacement, a sad story that has obliterated so many neighborhoods over the last several decades, but here it feels more blatant. Maybe because these funded institutions sit in an area so obviously neglected by the city for so long.

Just across the street from the Parkway there are Black people slumped on their stoops in drugged-out immobility due to decades of structural neglect, and next door there’s Motor House, an art gallery/theater/bar complex with a design show called “Undoing the Red Line.”

I walk out of the Parkway, and the graffiti on the street doesn’t look that different than the graffiti in the movie. Is it on display? As if to say: We want what happened in New York in the ’80s to happen here, now. There’s even an alley behind Motor House where graffiti is legal, and all day long there are photo shoots and staged parties promoting multicultural consumption in a segregated city.

Back on Charles, where there’s another movie theater, and then half a block of upscale bistros, and then everything ends at the bridge over the highway and there’s the train station, illuminated. I turn the corner and there’s some huge new building like a spaceship that’s landed to promote gentrification, so much air conditioning that there’s a giant puddle in the asphalt.

Oh, wait, that’s the building from the flyer, the Nelson Kohl Apartments, this is it, with a wood-paneled entry and a white cube gallery in the lobby showing bland abstract art, two rectangular fiberglass planters in front, painted black and textured to look like cement. Two grasses planted to one side, and then four almost-dead grasses on the other. The entrance faces the parking lot over the highway, with the train station on the other side. I stand outside to watch for anyone going in, but they must all be inside with their air conditioning.

I decide to go to the show at Motor House—the bar in front looks like a suburban advertisement for urban living, but the show in the lobby is actually about redlining. It’s mostly about New York and DC, although I do learn a few things about Cross Keys Village, where I went with Gladys as a kid, a sprawling gated housing development in Baltimore—a mixture of townhouses, a hotel, and mid-rise buildings in a leafy enclave, complete with a Frank Gehry–designed high-rise and a mall that includes Betty Cooke’s modernist gift shop that Gladys loved.

Apparently Cross Keys was marketed to both Black and white home owners when it was built in the 1960s, unlike the whites-only history of neighborhoods nearby, like working-class Hampden and posh Roland Park.

At Motor House they have a sign thanking the city for funding the space—I look it up when I get home, and it cost six million to renovate, funded by an organization called BARCO, or Baltimore Arts Realty Corporation, dedicated to “creating working spaces for Baltimore’s growing community of artists, performers, makers and artisans.” BARCO also recently completed an $11.5 million renovation of another space in the area, Open Works.

I look up the Parkway Theatre, and the renovation cost $18.5 million, including a five million grant from a Greek foundation. So there was international funding involved. For a movie theater in Baltimore. Then there’s the nineteen million spent by another nonprofit developer, Jubilee, to renovate the Centre Theatre to house the Johns Hopkins and MICA film programs right around the corner. This is a staggering amount of money in a city struggling for basic services.

All this empty corporatized language promoting Baltimore as an arts hub, a creative crossroads, a robust creative sector, an incubator for the creative economy. Which fits right in with the marketing of the Nelson Kohl Apartments, named after two famous dead designers who had nothing to do with it, and claiming to be THE ART OF BALTIMORE, with studios starting at fifteen hundred dollars, “surrounded by art, music, restaurants, bars, movie theaters, and one of the world’s premiere art colleges. When you live here, you can paint your own canvas—differently every day.”

Fifteen hundred dollars for a studio, in a city that’s mostly in collapse. Walking back up Charles, there’s a performance space in a former dry cleaner’s where everyone looks like the people in the Basquiat movie—the same ’80s outfits, only now everyone’s wearing all black, you can’t even have fun anymore with your studied indifference. Crossing the street to walk home—past the Crown, where I danced my ass off to terrible ’80s music and campy projections on white sheets, and everyone stared at me but no one approached.

Past the Eagle, another old building gutted and renovated with a surprising amount of money—usually a leather bar doesn’t have an upstairs cabaret and dance floor, a leather shop with an art gallery, and multiple streamlined spaces on the main floor. Not that anyone in the bar was friendly, but at least there were nice bathrooms.

You look for what you can’t find elsewhere, in neighborhoods where people are having trouble finding anything, and then eventually there isn’t any neighborhood except the one that replaced the neighborhood.And then I go into the convenience store where the register is behind bulletproof glass, my usual place to get an unrefrigerated bottle of water. A trans woman shaking a bit from drugs is ordering knock off perfume, chewing gum, talking on the phone: “I’m on the stroll.” A drug dealer steps in front of me to count out a huge stack of bills.

I get my bottle of water, and then back on the street I’m thinking about all the contrasts—the NPR studio with signs out front that say WARNING DON’T SIT HERE WALL IS UNSTABLE, the members-only jazz club that I assumed before was a Black space, but when I walk by now it’s all white guys outside, in between sets.

All the businesses that are never open, but the storefronts still advertise what was there before. The rehab center is the fanciest building on the block—across the street there’s a new art gallery featuring Black artists, in an old brick building.

And I find myself invigorated by the contrasts, the possibility for something surprising to happen—only this is how gentrification works. You look for what you can’t find elsewhere, in neighborhoods where people are having trouble finding anything, and then eventually there isn’t any neighborhood except the one that replaced the neighborhood.

______________________________

Touching the Art by Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore is available via Soft Skull.