“The Frisson of Pure Evil.” An Oral History of the Release of the Velvet Underground’s First Album

“There were just so many layers and so many colors. Even if all the colors were dark.”

“We all knew something revolutionary was happening. We just felt it. Things couldn’t look this strange and new without some barrier being broken.”

–Andy Warhol

*

Lou Reed: When we were working with Andy, we were doing our shows and we weren’t even making enough money to put the show on the next day, so Andy would go and do commercial art things constantly to get money to put on the show. That’s how we stayed together. It was all down to Andy. Because for a lot of bands in the Sixties, it was a lot of fun because they could all get signed and those record company people had no idea what was happening, so they were just signing everybody.

Unfortunately, it happened after the Velvet Underground, so we didn’t get any of the big money. We got, like, nothing and then after us, all of a sudden, all these bands were getting millions of dollars. It would have been nice if we’d got something, but we didn’t.

On March 12, 1967, in the US, Verve finally released the Velvet Underground’s first album; parts of it were almost a year old. Lou Reed said that they were signed by MGM not because they were so enamored with their music, but because Warhol had already agreed to do the cover. The record wouldn’t be released in the UK until November. The US cover marked a spectacular breakthrough in the commercialization of music, while also looking like a work of art. Warhol elevated the humble banana to icon status, just like he’d done with Campbell’s soup cans in 1962. The original album also came with a sticker over the banana (and was almost certainly a reference to Warhol’s film Eat, made in 1964). The instructions were “peel slowly and see,” and when you did you found a pink fruit underneath. It was saucy, and it was autonomous, having nothing at all to do with the band. Warhol’s alternative design was going to involve images of plastic surgery procedures—nose jobs, breast jobs, “ass jobs,” etc. On hearing the final album at the end of 1966, the record company decided to postpone its release by several months, unsure exactly how to market it. They’d paid for it, but they hated it. When it eventually did come out, it met with a disastrous combination of disdain, indifference, hatred, and bewilderingly awful sales. Because of the nature of the lyrics, many record stores simply refused to stock it.

In 1966–67, people didn’t write songs about buying drugs, which is why “I’m Waiting for the Man” was so transgressive. The song was sonically advanced too, not least the way the instrumentation echoed the sound of a train heading to the intersection of 125th Street and Lexington Avenue, East Harlem. It was gritty, challenging, and almost cinéma vérité, a paperback short story.

“Heroin” was equally shocking, seven minutes in which Cale’s shrieking viola shrouds the scene while Moe Tucker’s heartbeat drumming replicates a dream-like state. Ditto “Venus in Furs,” the title taken from Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s novella of the same name, a copy of which Reed apparently found on the street. At the time, sadomasochism wasn’t just never discussed, even its existence was called into doubt. It certainly wasn’t the subject of pop songs.

After listening to the first acetate, producer Tom Wilson thought the album lacked a discernible single and asked Reed and Cale to write a new song for Nico to sing.

Written by the pair in the early hours after a long Saturday night, “Sunday Morning” (a candy kiss with a kick in it) was almost a lullaby. But while it was certainly commercial, Reed decided to sing it himself, relegating Nico to background vocals. In the studio, Cale played a celeste rather than a piano, giving the song an eerie undertow.

Verve’s press ads for the album were beyond embarrassing. They read as though they had been created by someone with no knowledge of a) pop culture, b) youth culture, c) advertising: “What happens when the daddy of Pop Art goes Pop Music? The most underground album of all! . . . Sorry, no home movies. But the album does feature Andy’s Velvet Underground (they play funny instruments). Plus this year’s Pop Girl, Nico (she sings, groovy). Plus an actual banana on the front cover (don’t smoke it, peel it).”

Lou Reed’s favorite review of the album, which he used to repeat to anyone who would listen, was: “The flowers of evil are in bloom. Someone has to stamp them out before they spread.” Reed had been vindicated.

Lou Reed: Andy made the Velvet Underground possible. By producing that LP, he gave us power and freedom. I was always interested in language, and I wanted to write more than “I love you—you love me—tra la la,” you know? He wasn’t the record’s producer in the conventional way that when record company people would say, “Are you sure that’s the way it should sound?” He’d say, “Sure, that sounds great.” That was an amazing freedom, a power, and once you’ve tasted that, you want it always.

David Bowie: The Velvet Underground was a life-affirming moment for me. I think “I’m Waiting for the Man” is so important. My then manager brought back an album from New York, having been given it by Andy Warhol. This was months before it actually came out, it was just a plastic demo of the Velvets’ very first album. He was particularly pleased because Warhol had signed the sticker in the middle. He said, “I don’t know why he’s doing music, this music is as bad as his painting,” and I thought, “I’m gonna like this.” I’d never heard anything quite like it, it was a revelation to me.

It influenced what I was trying to do—I don’t think I ever felt that I was in a position to become a Velvets clone but there were elements of what I thought Lou was doing that were unavoidably right for both the times and where music was going. One of them was the use of cacophony as background noise and to create an ambience that had been unknown in rock, I think. The other thing was the nature of his lyric writing which for me just smacked of things like Hubert Selby Jr., The Last Exit to Brooklyn, and also John Rechy’s book City of Night. Both books made a huge impact on me, and Lou’s writing was right in that ballpark. It was Dylan who brought a new kind of intelligence to pop songwriting but then it was Lou who took it into the avant-garde.

This music was so savagely indifferent to my feelings. It didn’t care if I liked it or not. It couldn’t give a fuck. It was completely preoccupied with a world unseen by my suburban eyes.Jimmy Page: When I eventually heard the album it was exactly as they had sounded when I saw them. I’d never heard music go into those areas before, and it all made sense on record. The material on the first album is almost cinematic. Each song is so different, each song has such a strong identity. The crafting of it is absolutely incredible. The musicianship is just groundbreaking. There were just so many ideas on that album. Lou Reed doing “Sunday Morning.” There were just so many layers and so many colors. Even if all the colors were dark.

David Bowie: The first track [“Sunday Morning”] glided by innocuously enough and didn’t register. However, from that point on, with the opening, throbbing, sarcastic bass and guitar of “I’m Waiting for the Man,” the linchpin, the keystone of my ambition was driven home. This music was so savagely indifferent to my feelings. It didn’t care if I liked it or not. It couldn’t give a fuck. It was completely preoccupied with a world unseen by my suburban eyes.

Jon Savage: The first Velvet Underground album is such a concentrated package that it is not surprising that pop culture took twenty or so years to catch up. The Velvet Underground & Nico straddles pop and the avant-garde with the decisive quality of a preemptive strike. Encoded within the record are references to authors like Leopold von Sacher-Masoch and Delmore Schwartz, Lou Reed’s teacher, whose In Dreams Begin Responsibilities is the definitive account of the immigrant experience in the first quarter of this century.

Best of all was the way the thing looked: a blurred picture of the group with five separate shots underneath, so lit that you could hardly tell which were the boys and which were the girls. This severe androgyny went further than English attempts at the same game, which had the innocence of childhood. Here the deadpan, blurred look is matched by lyrics about matters that were not hitherto the subject of pop songs. Underneath everything is John Cale’s viola, penetrating enough to bring down the walls of Jericho.

At one stroke, the Velvet Underground expanded pop’s lyrical and musical vocabulary. This was deliberate and gleeful: contemporary interviews had Reed blithely discussing a Cale composition “which involved taking everybody out into the woods and having them follow the wind.” Reed was in love with the doo-wop that we’d never heard in Britain, the Spaniels and the Eldorados, intense, slow ballads with a lot of heart from the early/mid Fifties. Sometimes, these songs would slow down to the point of entropy—an oasis of calm and a refusal of the harshness of ghetto life. The simple fact is, to hear the record in 1967 was to be let into a secret world, once you’d got past the first frisson of pure evil. Like every other great pop record, it changed your life.

_____________________________________

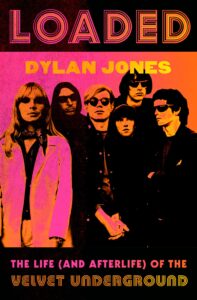

Excerpted from the book LOADED: THE LIFE (AND AFTERLIFE) OF THE VELVET UNDERGROUND. Copyright © 2023 by Dylan Jones. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.