It’s odd to think that this history of artist David Edward Byrd started with a trip to the bathroom… but it did.

However, this visit to the john was far removed from much of the history you’re about to read. It didn’t take place in the artist hatchery of 1960s Carnegie Tech (later Carnegie Mellon University), where Byrd studied. It wasn’t among the grimy streets of New York, where Byrd first created artwork for the Fillmore East. Nor did it happen in the slick confines of Broadway, where Byrd redefined the art of theater. This bio break happened in the safe and sober glaze of 1990s Los Angeles, a time of Macintosh computers and Johnny Rockets burger joints.

At that time, I was managing graphic arts for Geffen Records in Hollywood, so I knew firsthand that the art of rock had matured. Gone were the days of French curves and cash payments; designers had computers and worked under contract. These were sober days when smoking in the office was banned and drunken lunches at El Coyote (while not unheard of) were fading faster than vinyl records. The fact that I spent more nights in USC’s business school than on the Sunset Strip says much about the era. Byrd and I first met when I was working with his husband, Jolino Beserra, on CBS ads for TV Guide, probably the most uncool art job in the industry. I only got the gig because someone happened to call someone. It was an accident.

By the 1990’s, David Byrd’s life was more Eisenhower-era domesticity than the hippie commune existence of his youth. This might explain why Byrd and Beserra decided to host a “meatloaf” party in 1990, which I attended. The homey little love nest they occupied in Beachwood Canyon was a curated combination of Day of the Dead and Danny Elfman. As the night’s meat-fest wore on, I became less interested in the art talk than the Wisconsin cutie sitting a little too close to me at the table.

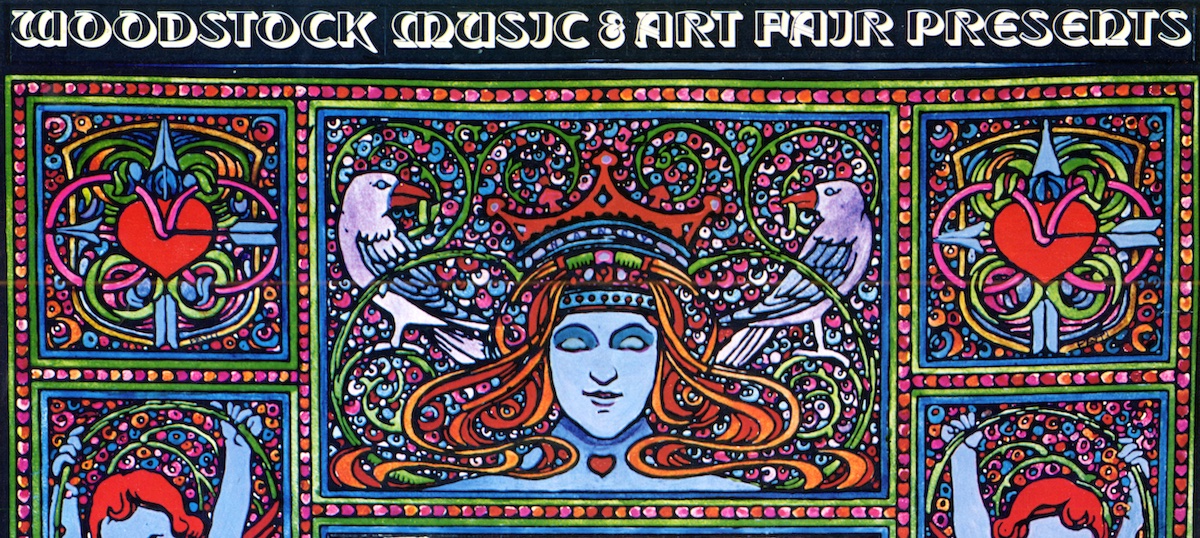

It was about this time that the aforementioned trip to the john took place. As I emerged from the bathroom, business completed, I noticed a small, framed artwork tucked in a space next to the door, as if it were hiding (or hidden) out of the limelight. I sat for a moment and admired the neoclassical painting of a woman with a water jar, surrounded by wild multicolor hearts, arrows, and cupids. The Victorian aesthetic fascinated me, as did the hard-to-read type that stated “An Aquarian Exposition.”

I settled back in next to Miss Midwest and asked about the piece. In his nasal voice, whistled through a walrus mustache, Byrd told me it was the original poster for the 1969 Woodstock festival. To this I asked, as I’m sure many had before, “Wait, didn’t the Woodstock poster have a bird and the guitar?” To this Byrd replied, “There’s a story.”

That dinner was thirty-plus years ago, and it was the first story Byrd ever told me. How he was hired to produce a poster for what became the infamous Woodstock Festival, and how the festival promoters were dicked around and had to move the venue a number of times, and how they needed the poster changed, and how Byrd was in the Caribbean and unreachable, and how Arnold Skolnick got the call to create an alternate, and how it all came together by accident. But as you’ll see, accidents play a huge part in the story of David Edward Byrd.

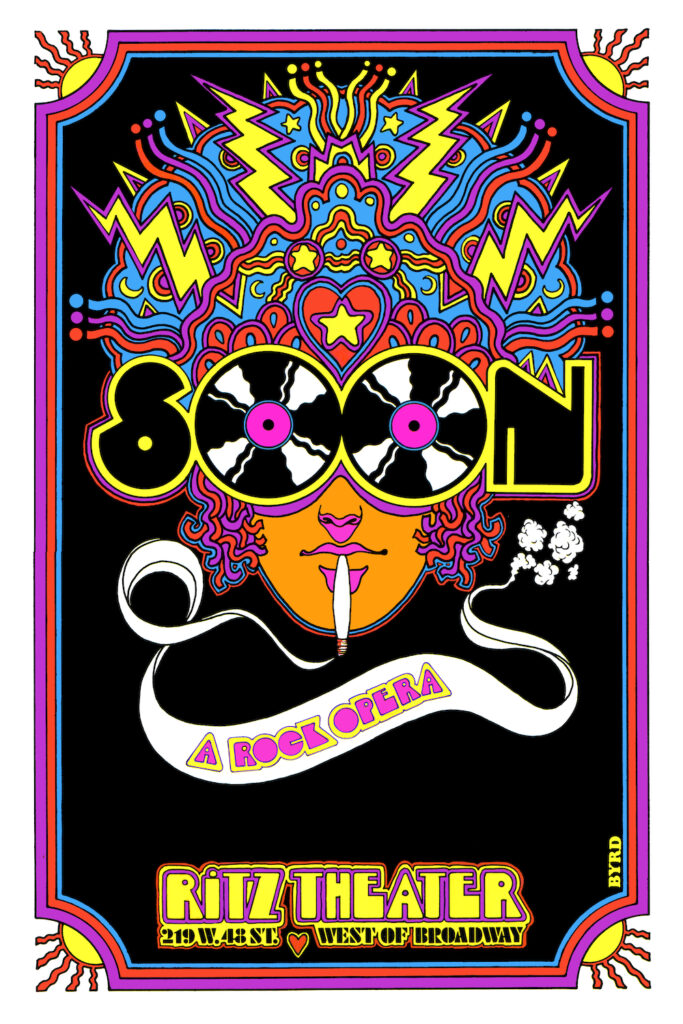

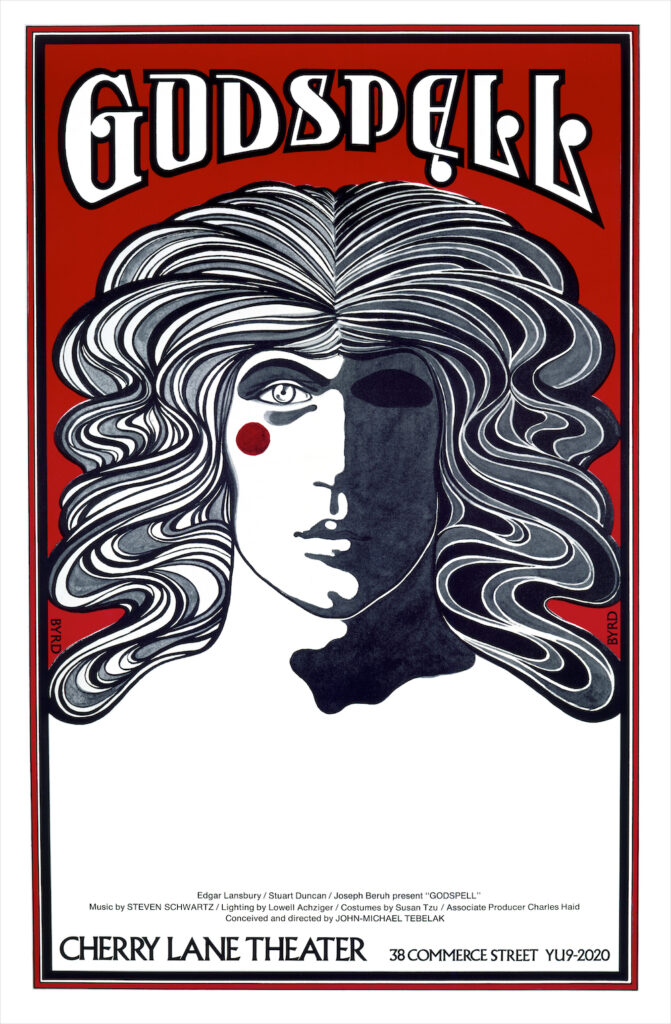

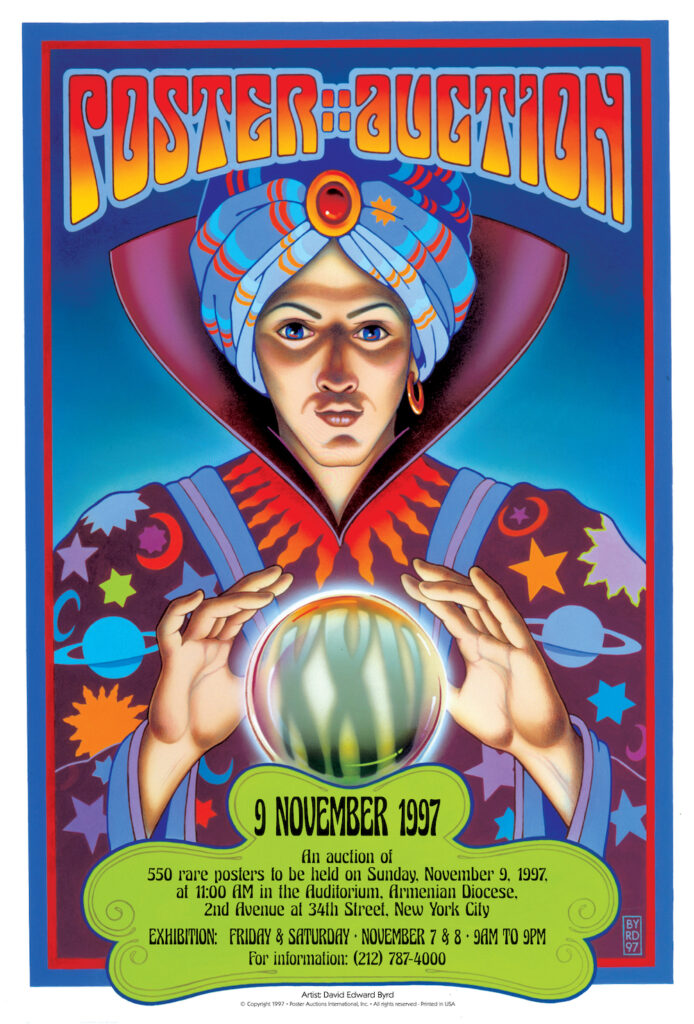

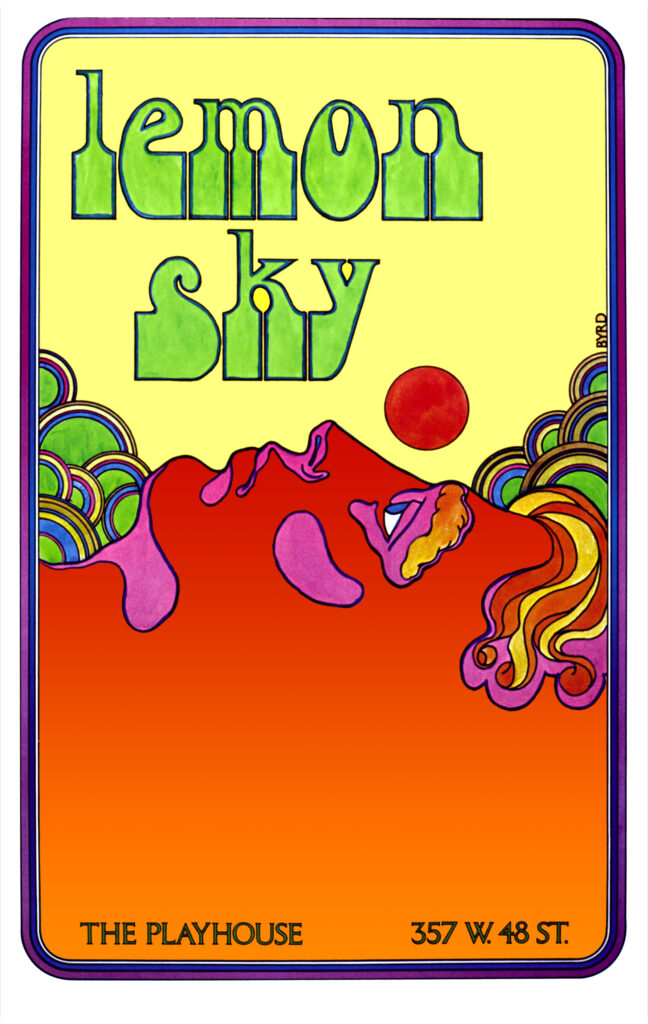

In the 1960s, Byrd and a handful of talented contemporaries defined the art of rock music. Before them, there wasn’t much imagery to characterize this new art form. But Byrd didn’t start out to create a name in graphic arts. Quite the opposite. As a star student at Carnegie Tech, where commercial and fine art were strictly separated, Byrd had his sights set on a life in fine art. He wanted to be Francis Bacon, not Saul Bass. But the phone rang, and some fellow Carnegie students were helping a guy named Bill Graham open a music venue in New York City, and they needed an artist. And here’s the kicker: while Byrd is now considered one of the finest graphic artists of the twentieth century, he never really studied graphic arts. By his own admission, he didn’t even know anything about typography. But talent is talent, and David was the best artist they knew, so he got the call. Boom . . . accident.

Now, fast-forward to the 2020s. The pandemic hit, and I spent my confinement creating and hosting an online music trivia show. David Byrd was a guest, telling one incredible story after another. Jimi Hendrix is building his infamous Electric Lady Studios in New York, and did Byrd wanna see it? Byrd gets paid for creating a poster for the Who, gets mugged on the way home, and Bill Graham (the mensch that he was) paid him again. The legendary Broadway producer Hal Prince allows David to submit a design for his new production called Follies, but he had to do it for free since they’d run out of concept money. Byrd gets the gig and reimagines Broadway art. Again . . . accident.

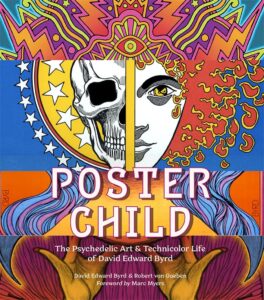

You didn’t have to be a genius (which I am not) to see that there was a book here. Which was lucky for me because, as odd as it seems, no one has ever really told Byrd’s story. Maybe nobody asked, or maybe it fell through the cracks. I didn’t go into this wanting to write a book, I just needed a guest for my show, and Byrd was a famous music guy I knew. Another accident.

Byrd’s life story has all the makings of a Hollywood biopic: a glamorous, monied, and deeply flawed childhood filled with drunken parents and neglect. Hippie communes, life-threatening car crashes, big names, and even bigger drugs. Byrd spent the 1970s creating seminal artwork for rock and Broadway, only to wake up facedown on a Manhattan sidewalk. There’s no limit to how low this story goes. Then he embarked on a life-saving exodus to Los Angeles, where the only crash pad is sharing bunk beds with a nine-year-old kid. Byrd then experienced a proverbial rebirth, courtesy of a successful methadone treatment and a lifelong partnership with a man twenty years his junior. But through all the highs of a Grammy and the lows of skin popping, Byrd never stopped working. To this day, he has missed exactly one deadline, and he can’t stop flogging himself for it.

The biggest challenge in creating this book was filtering the immense number of stories and images. I never realized the depth of Byrd’s portfolio until I asked him to discuss the fascinating album covers he created for Vanguard Records in the ’70s. He couldn’t remember a goddamn one of them. Most of us are lucky to do one note- worthy thing in our life; Byrd has them stacked so high that whole categories get lost. (For the record, the album covers never did make it into this book.)

Going back to the beginning and that dinner party, a few great things came from that chance encounter. I ended up marrying that cutie from Wisconsin, and we’re going on thirty years. And I was also brought into the orbit of David Edward Byrd, and I am beyond honored to reintroduce his artwork to the world. In the end, I’d love to say this volume was the result of a grand strategy. But it all came together, as fantastic journeys often do . . . by accident.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Poster Child: The Psychedelic Art & Technicolor Life of David Edward Byrd by Robert van Goeben and David Edward Byrd is available from Cameron Books / Abrams. Used with the permission of the publisher, Cameron Books/Ambrams. Copyright © 2023 by Robert van Goeben and David Edward Byrd.