Dissenting in Style: How Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Collars Became Political Signifiers

Elinor Carucci and Sara Bader on RBG's Decision to Buck the Supreme Court's Sartorial Traditions

When Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg took her seat on the Supreme Court bench on August 10, 1993, she became the second female to serve on the country’s highest court, joining Justice Sandra Day O’Connor(nominated by President Ronald Reagan in 1981). In the court’s group portrait from RBG’s first term, the nine justices, posed in front of red velvet curtains, wear flowing black judicial robes. The uniform is a simple but powerful symbol: concealing the individual’s body, it conveys impartiality and the somber, collective responsibility to uphold the Constitution. Justices Ginsburg and O’Connor flank the seven male justices.

There isn’t a dress code for Supreme Court justices—the black robe has been worn over the years out of tradition. For the seven male justices in this 1993 court photograph, the white button-down shirt collars and ties (and one cheerful bow tie) are distinguishing fashion choices. RBG and Justice O’Connor, meanwhile, set themselves apart from their male colleagues, each adorning their uniform with a traditional white jabot—a a frill of lace or other type of fabric fastened at the neck and worn over the front of a shirt or robe.

Their colleagues overseas inspired this sartorial accent—barristers in England have long worn jabots, along with gowns and wigs, as part of their customary courtroom attire. French magistrates wear jabots as well, known there as rabats. Lace was considered a marker of wealth and status, not gender, from its origins until the late eighteenth century, and lace neckpieces, such as jabots and rabats, were traditionally worn by men.

It is worth noting that although Justices O’Connor and Ginsburg accessorized their robes with jabots and collars that were seen as feminine in our time, they were appropriating what was once a symbol of masculine power. Purchasing jabots in the United States, though, proved challenging: “Nobody in those days made judicial white collars for women,” Justice O’Connor remembered. “I discovered that the only places you could get them would be in England or France.”

Their decision to feminize a traditionally male uniform was a radical one. By wearing these decorative accessories, both Justices O’Connor and Ginsburg communicated that a woman could be both intellectually rigorous and feminine. “[Ginsburg’s] collars re-inject the concept of ‘body’ into the disembodying judicial robe,” notes author Rhonda Garelick, “signaling not only the presence of a woman, but by extension, the presence of a biological human body—which demands acknowledgment and consideration.”

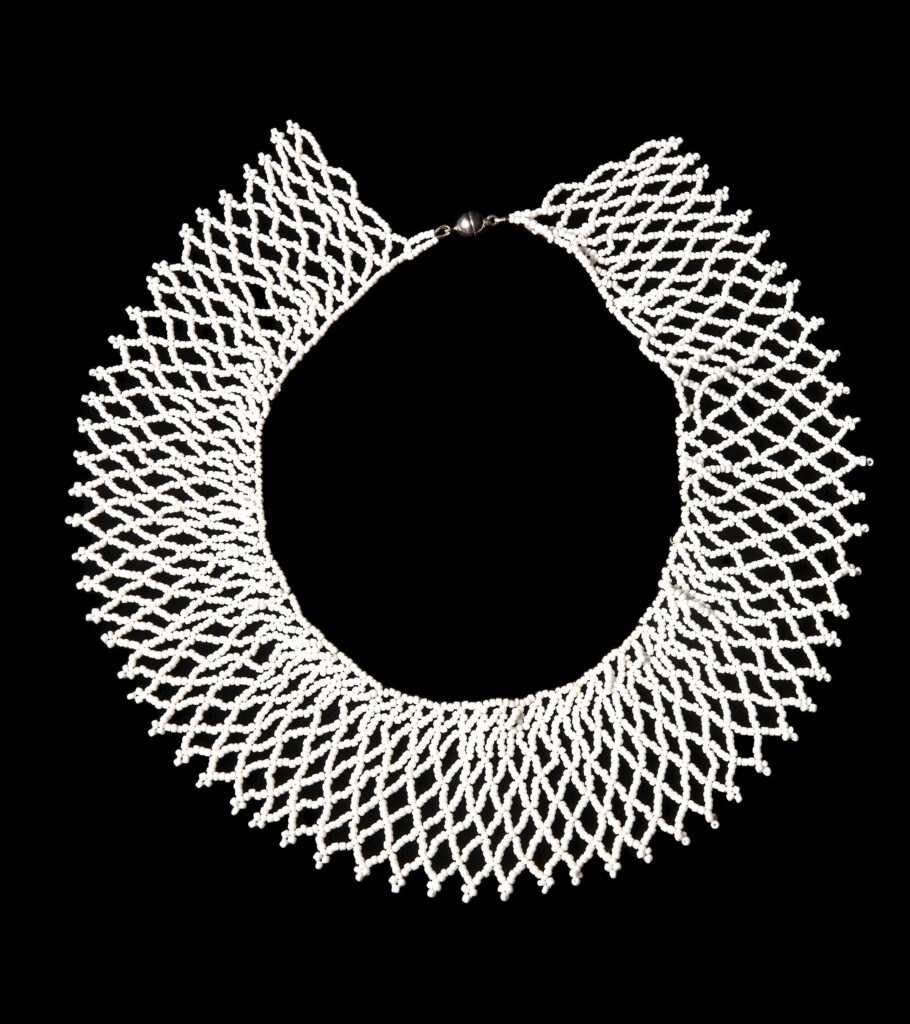

By wearing these decorative accessories, both Justices O’Connor and Ginsburg communicated that a woman could be both intellectually rigorous and feminine.This jabot, although more decorative, is reminiscent of the one RBG wore in that first group photograph and in her earlier years on the Supreme Court. The lace collar—with its modern rounded flower petals, leaves, and scrolls—offsets the formality of the crisp, pleated form. Over the years, RBG’s collection of neckpieces expanded considerably in number and style, from classic white jabots like this one to intricate lace pieces to vibrant beaded collars. She acquired some in her travels, and cherished those gifted to her by colleagues, artists, and fans from all over the world.

*

“This is my dissenting collar,” RBG told Katie Couric in a 2014 interview, referring to a limited-edition glass stone necklace with a velvet tie. “It looks fitting for dissent.” Justice Ginsburg received the neckpiece, made by Banana Republic, in a gift bag when she accepted a lifetime achievement award in 2012 at Glamour Magazine’s annual Women of the Year ceremony. A few years later, in an interview with Jane Pauley, RBG elaborated—but just a bit: “This is my dissenting collar. It’s black and grim.”

Justice Ginsburg was known for writing precise and forceful dissents when she disagreed with the majority ruling. “When a justice is of the firm view that the majority got it wrong, she is free to say so in dissent,” she wrote in a 2016 op-ed in the New York Times. “I take advantage of that prerogative, when I think it important, as do my colleagues.”

Dissents become part of case law alongside their majority opinions, and can be referenced in future cases. In the words of an earlier chief justice of the Supreme Court, Charles Evan Hughes, often quoted by RBG, dissents are meant to appeal “to the intelligence of a future day.” RBG’s reading of her incisive dissents from the bench increased with frequency over the years, which she attributed to the ever more conservative makeup of the court: “After 2006, the sight of the tiny black-robed justice rising from the bench wearing her ‘black and grim’ dissenting collar and clutching her papers became a familiar sight,” wrote biographer Jane Sherron De Hart. Ginsburg drafted a hundred and fifteen dissents for the Supreme Court—between her first, in 1994, and her last, in 2020. “Every time I write a dissent,” she told Bill Moyers in her last interview, “hope springs eternal.”

In 2007, when she was the sole female on the Supreme Court—Justice O’Connor had retired the previous year—RBG delivered a sharp dissent in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. In response to the Supreme Court’s ruling in a 5–4 decision that an employee cannot sue for pay discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 unless she brings her claim within a hundred and eighty days of her employer’s discriminatory pay decision, she countered with these words: “Four members of this Court, Justices Stevens, Souter, Breyer, and I, dissent from today’s decision. In our view, the Court does not comprehend, or is indifferent to, the insidious way in which women can be victims of pay discrimination.”

She appealed to Congress to correct the mistake made by her colleagues, and two years later Congress followed through, passing the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, the first piece of legislation President Obama signed in office—a copy of which RBG framed and hung in her chambers.

She wrote another forceful dissent for the 2013 case Shelby County v. Holder, in which the majority struck down a key section of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, deeming it unconstitutional. RBG did not mince words: “Hubris is a fit word for today’s demolition of the VRA [Voting Rights Act].” Under the 1965 Voting Rights Act, certain jurisdictions with a history of discrimination were required to submit any redistricting plans to the US Department of Justice for preclearance before they could make changes to voting procedures; this was the key section at play.

Toward the end of her dissent, which was joined by Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan, Ginsburg offered this analogy to explain why eliminating the need for preclearance was senseless and shortsighted: “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

According to her biographer De Hart, when RBG read the dissent aloud, she quoted Martin Luther King Jr. His words are not included in the written dissent: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” But she clarified that it could only bend toward justice “if there is a steadfast commitment to see the task through to completion,” ending with “That commitment has been disserved by today’s decision.”

In 2014, she wrote and delivered another eviscerating dissent in response to the Supreme Court’s 5–4 ruling in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores. The ruling asserted that a corporation cannot be forced to provide its employees with insurance coverage for contraception when doing so violates the corporation’s religious beliefs. The decision effectively imposed the company’s religious views on its employees. RBG explained that the employers and all who share their beliefs may decline to acquire for themselves the contraceptives in question. But that choice may not be imposed on employees who hold other beliefs. Working for Hobby Lobby…in other words, should not deprive employees of the preventive care available to workers at the shop next door.

She wore the dissent collar in the courtroom but also on significant occasions off the bench, including the day following Donald Trump’s election in 2016. Banana Republic reissued the piece in 2019 for a limited time, now called the Notorious Necklace, donating fifty percent of the proceeds to the American Civil Liberties Union Women’s Rights Project, which Justice Ginsburg cofounded in 1972. The company reissued it again in 2020, as a tribute to the late justice, this time donating the proceeds until the end of that year, up to a half million dollars, to the International Center for Research on Women.

“Justice Ginsburg’s dissents were not cries of defeat,” Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt reminded mourners when she eulogized RBG in the Capitol’s Statuary Hall. “They were blueprints for the future.”

*

This white beaded collar from Cape Town, South Africa, was Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s favorite. Among a variety of milestone moments, she wore it to President Obama’s address to the joint session of Congress in 2009; for his State of the Union, in 2010, when he described the country’s “deficit of trust” in the government and the imperative of fixing it; in 2011, after the Democrats had lost control of the House a few months earlier; in 2012, as Obama geared up for the fall election; and for Pope Francis’s address to the joint session of Congress in 2015—the first time a pope addressed Congress.

She wore the dissent collar in the courtroom but also on significant occasions off the bench, including the day following Donald Trump’s election in 2016.It was also the collar she chose to wear for various court group photographs, for her own portrait that hangs in the Supreme Court, for her 2015 portrait as one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential people, and for Nelson Shanks’s 2012 portrait The Four Justices. Shanks’s epic, large-scale oil painting depicts the four female justices who had served on the US Supreme Court since 1981—Sandra Day O’Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan.

“After Sandra left, I felt very lonely,” Justice Ginsburg remembered, and it was the wrong image for the schoolchildren, particularly, to come in and see this bench with eight men and one very small woman. Now, I sit toward the center by virtue of seniority and Justice Kagan is on my left, and Justice Sotomayor is at my right. We look like we are all over the bench. We are here to stay.

It is fitting that her favorite collar is from South Africa: she had great reverence for the constitution of the Republic of South Africa, ratified in 1996, which she described as “a deliberate attempt to have a fundamental instrument of government that embraced basic human rights” with an “independent judiciary.”

______________________________

Excerpted from the book The Collars of RBG: A Portrait of Justice by Elinor Carucci and Sara Bader. Copyright © 2023 by Elinor Carucci and Sara Bader. Photographs copyright © by Elinor Carucci unless otherwise noted. Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.