Featured image: Abito corto in pizzo con disegno Azma (1971). Short lace dress with the Azma print (1971). From Ken Scott.

What does fashion express with a show? And what does a fashion show signify for a designer who shapes his thinking through clothing? The question is a legitimate one when you watch events like those of Demna Gvasalia for Balenciaga, and before them those of the late Alexander McQueen—two designers capable of taking a stance on contemporary reality through their complex, imaginary, and theatrical installations. But the question especially needs to be asked when the story is told about the designer who, more than any other, revolutionized fashion shows, turning them into absolute performances for the first time ever.

It was the 1960s, and Italian fashion was presented at Palazzo Pitti, in Florence, without much fanfare. Surrounded by the elegance of the institution and a practical sense, there were models, there were splendid clothes, and, of course, there were elegant clients who, while seated on Chiavari-style chairs, observed what they saw, assessing each outfit in detail before signing the orders for their own wardrobe or for their own boutique. In short, the attention was focused on the product. The outfit was everything. Was anything missing?

Cappotto in raso pesante con disegno Bindu (1969). Heavy satin coat with the Bindu print (1969).

Cappotto in raso pesante con disegno Bindu (1969). Heavy satin coat with the Bindu print (1969).

Perhaps something was indeed missing. And this became clear with the arrival of Ken Scott, a bohemian American artist turned Milanese entrepreneur for love of fashion. When he began to present his collections at Palazzo Pitti, first, and in Milan, later, it was a game-changer—for good. Suddenly, the attention grew, the focal points multiplied, as did the bursts of creativity. The outfit no longer had a life of its own; it was no longer the Sun. Rather, it became a part of the elaborate constellation that included the space in which it was presented, the installation, the mood, the soundtrack, the choreography of the models, the invitation that preceded the show, the dinner that followed, the communication, the audience of those invited. With Ken Scott, the show went from being a short film to a blockbuster movie. And what had been missing before soon became clear: entertainment. Better still: fun.

Ken Scott would say so with every chance he got, when he was interviewed by the magazines back then: “The fact is I find fashion shows so depressing,” he confided to the weekly Grazia in the early 1970s. His idea, at the time, was to design an amazing spectacle that he and his guests would be amused by, that would make them dance, interact, listen to music. Was the fashion show an excuse to party? Or was it the party that made the show a success on both a communicative and commercial level? “For me, fashion is first and foremost fun. My models are for people who are carefree and self-confident, who don’t choose an outfit because it has a designer label, but mostly because they think it’s fun. To be able to love my collections you have to be anti-bourgeois, of the people, aristocratic, but never mass media.”

Tessuto Lady Winter, 1986. Lady Winter Textile, 1986.

Tessuto Lady Winter, 1986. Lady Winter Textile, 1986.

But Ken Scott’s innovative and nonconformist spirit went much further. At the end of a revolutionary decade like the 1960s, Ken Scott went so far as to present both women’s and men’s fashion in the same show—it was a breath of change and innovation that at the time was known as “unisex” and foreshadowed by several decades the gender-fluid style and the co-ed collections of today’s fashion shows.

It was January 1967, and in the rooms of Palazzo Pitti Ken Scott’s revolutionary act unfolded. Like a full-fledged movie director, Ken Scott staged twenty-five famous couples from fifteenth- and sixteenth-century paintings in a collection he called Gli Amanti: there were Orlando and Angelica, Petrarch and Laura, Giovanni Boccaccio and Fiammetta, Hero and Leander… “Only Bacchus Covered in Sequins Was Missing” was the headline in the daily newspaper Il Giorno, criticizing what it labeled as “the desire to surprise at all costs,” even when it involved men’s tunics and caftans.

The truth of the matter is that for the first time ever, men’s and women’s wardrobes were interchangeable in the name of a revolutionary “total look” where nothing was mismatched and everything was perfectly en pendant. Just as he had always designed wigs, jewelry, and shoes in addition to women’s clothing, Scott had created the outfit for the man who accompanied her, a “matching man” designed to complete her and reinforce the overall visual impact. The idea was a huge commercial success in all the most fashionable boutiques.

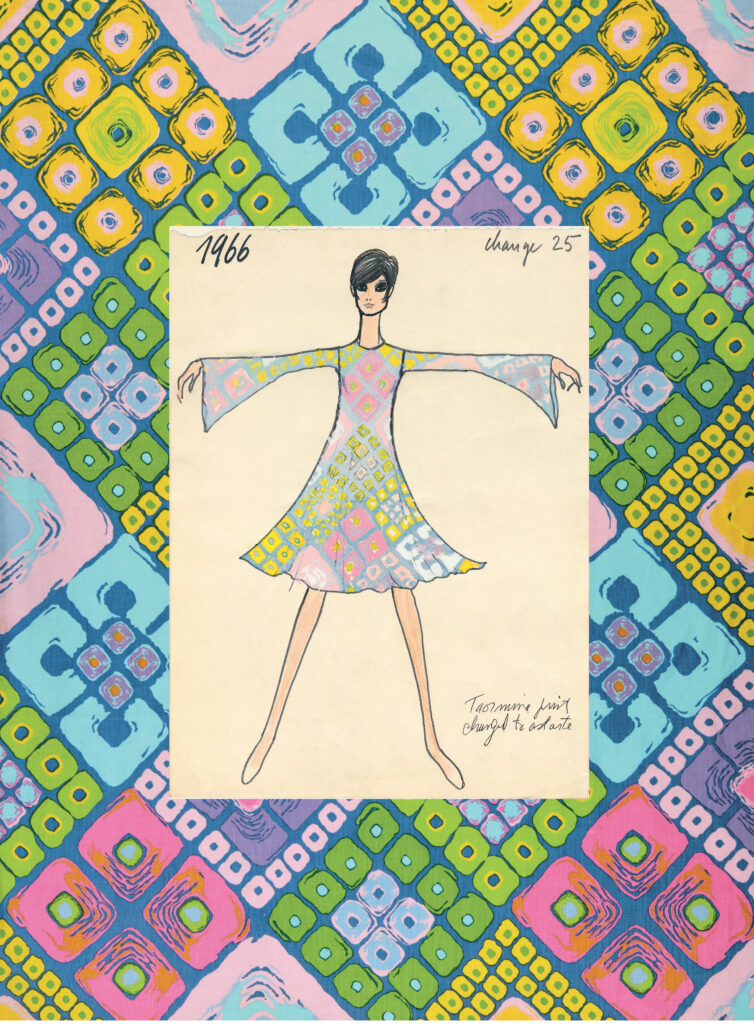

Carta prova per il tessuto Astarte, 1965, figurino per il film di Stanley Donan Due per la strada (1967). Test paper for the Astarte print (1965), figure for the Stanley Donan movie Two for the Road (1967)

Carta prova per il tessuto Astarte, 1965, figurino per il film di Stanley Donan Due per la strada (1967). Test paper for the Astarte print (1965), figure for the Stanley Donan movie Two for the Road (1967)

In January of the following year, at the Casina Valadier in the Roman garden of Villa Borghese, the unisex concept was once again on display, but this time in a beach fashion key: for the collection Bonnie Goes to Bombay, couples paraded down the catwalk wearing sailor-blue outfits or ones decorated with an anchor pattern in Ban-Lon. The guests in attendance included Michelangelo Antonioni, Monica Vitti, Princess Alessandra Torlonia, Rossella Falk, and Kay Thompson, invited first to a festive dinner and then to a dance party. “Why should the sexes dress dissimilary? Men and women go to the same places, do the same things, play the same games. Why does society say they have to dress differently? The old platitudes are nonsensical,” the designer remarked on that occasion.

Less than a year went by and Scott doubled the stakes. For the winter of 1968, on the Appia Antica, his imagination gave rise to a fashion show he called Circo. Ken Scott had created a bold performance filled with models and tightrope-walkers, jugglers and fire-eaters, clowns and animals, Pulcinellas and Pierrots wearing or accompanying unisex outfits made from Ban-Lon inspired by animalier motifs, raincoats with clown prints so that one would feel like laughing even when it was raining. There were also outfits inspired by the commedia dell’arte, in wild colors. His was “a show that will go down in the history of fashion,” wrote the style reporter Maria Pezzi, who in Una vita dentro la moda (Skira, 1998) declared that “he could have been the greatest theater impresario of our times.”

Outfit with the Infinito print (1968), with gilded and silvered leather jewelry by Sanders for Ken Scott. Photos by Alfa Castaldi for Vogue Italia, 1968.

Outfit with the Infinito print (1968), with gilded and silvered leather jewelry by Sanders for Ken Scott. Photos by Alfa Castaldi for Vogue Italia, 1968.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Ken Scott by Shahidha Bari, Federico Chiara, Pierre Léonforte, Renata Molho, and Isa Tutino. Copyright © 2022. Available from Rizzoli.