Making Sense of Santa, as a Science Reporter and a Parent

Nell Greenfieldboyce on Reason, Science, and Metaphorical Delights

When my son was almost two years old, we went to the office holiday party at NPR, where I work. He was happily eating cookies in a cafeteria crowded with revelers when Santa Claus burst into the room with a mighty HO HO HO. It was one of my colleagues (sadly, I can’t remember who), dressed up in a red suit and fake white beard, who greeted every child and boomed, “Have you been good this year?” My son watched him, wary. When Santa came over to us, my son cringed and hid behind my legs, looking as though he might cry. Santa held out a candy cane. My son refused to take it.

I admired the kid. Faced with an intrusive, looming, bizarrely-dressed stranger, he ignored social pressure and outright bribery in favor of his own assessment of the disturbing observable facts. Part of me regretted that I wasn’t going to have an adorable photo of him on Santa’s lap to send to his grandparents. But as a science reporter, I was fascinated to watch my children investigate the strange phenomenon that is Saint Nick.

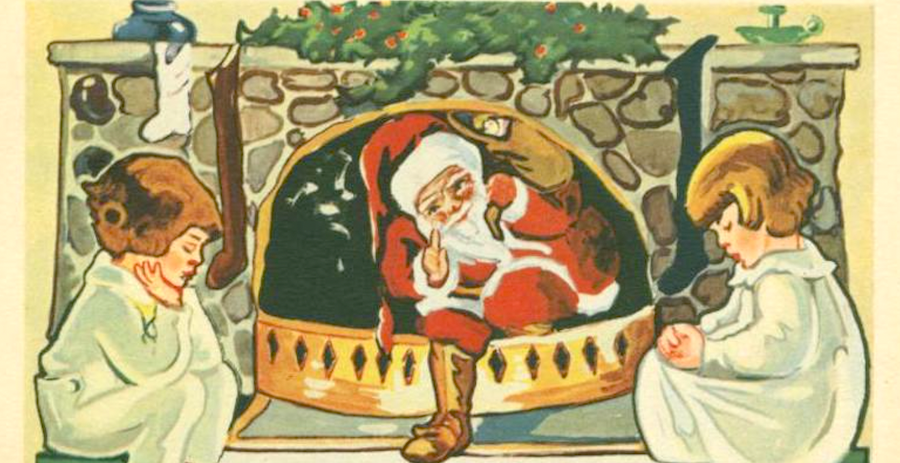

One night, when my son was about three, we were curled up in bed, reading “The Night Before Christmas.” Together, my son and I gazed at the picture in the book, a richly detailed rendering of reindeer with golden harnesses, pulling a tiny sleigh above snowy rooftops.

“Can reindeer really fly?” he asked.

“What do you think about that?” I asked.

“No!” he answered, immediately and decisively.

“I’ve never seen a flying deer,” I said casually, “but I love this illustration. I think it’s beautiful.”

I’d chosen my words carefully. Parents, armed with pronouncements from pop psychologists, have long traded tedious, judgmental barbs about the best way to handle Santa-related queries. It’s always “You’re lying to children and betraying their trust!” versus “You’re depriving children of magic and joy!” To me, though, fielding questions about Santa seemed like just one more task in my most difficult but essential duty as a parent: demonstrating how to walk a tightrope of honesty without falling into despair.

Compared to the abundance of stories and movies and songs about Santa, which bombard children all December long, the scientific literature on Santa, and especially on how this ubiquitous myth is perceived by young minds, is regrettably scant. Occasionally a medical journal will run a faux-serious article such as “Work-related skin diseases of Santa Claus” or “Santa Claus: A Global Health Threat.”

And some physicists have playfully used Einstein’s theory of relativity to account for Santa’s impressive feats through time and space—if Santa moves fast enough, clocks will slow down, allowing him to visit billions of homes in just one night, and his body will shrink, letting him slip down chimneys.

Children, whose knowledge of physics is less esoteric but nonetheless robust, conduct their own analyses. “Santa is purported to engage in activities that violate physical principles known even to infants,” researchers wrote in one study. They noted that kids may initially accept trusted adults’ testimony about Santa’s fabulous abilities, despite any inward doubts.

But as children develop a more mature understanding of what’s physically possible, their questions become increasingly pointed. While the very young tend to ask for factual details about Santa (“Where does he live?”), older kids are more likely to ask for explanations of his superhuman traits (“How can he watch everyone to see if they’re bad or good?”)

Most children know the truth by the age of seven or so. In 1994, one child psychiatry journal featured a study that claimed to be the first investigation of how both children and their parents reacted to this “ultimately inescapable encounter with reality.” Only a third of the kids in this study got the straight dope about Santa from their parents. More than half of the children figured out that he was fictional on their own. While the kids reported a range of emotions about this discovery, most often they felt “surprised,” “happy,” “good,” and “relieved.”

Their parents, by contrast, most commonly reported feeling “sadness.” Some parents told the researchers that Christmas felt less magical. Those parents were probably disappointed to see their precious cuties growing up and losing their much-ballyhooed “childlike sense of wonder.”

That phrase has never made sense to me. I question how much wonder children actually feel. My own young kids approached everything from a moving walkway to dog drool to Santa Claus with a matter-of-fact inquisitiveness that any scientist would recognize and respect. A toddler’s instinct, upon encountering something unfamiliar, is not to revel in awe; a baby will, without hesitation, grab the closest novel thing, wave it in the air, smash it on the ground, suck on it, tear it apart—in short, try to figure it out.

I remember my daughter as a preschooler, pointing to someone in a Santa-suit on a street corner. “Is that Santa?” she asked.

“That is a person dressed up as Santa,” I answered. “Playing Santa is like a big game that people enjoy this time of year because winter is cold and dark and it’s good to have something fun that we can all do together.”

I never misled my children, but I noticed that whenever I acknowledged Santa’s non-existence, I felt compelled to tack on some kind of spiritual consolation prize, like the beauty of art or the comfort of fellowship. It’s as if I worried that by just baldly stating “Santa is a made-up story,” I’d be leaving the children unprotected against, well, their “ultimately inescapable encounter with reality,” as those psychology researchers put it, in a word construction that sounds an awful lot like a euphemism for death.

I question how much wonder children actually feel. My own young kids approached everything from a moving walkway to dog drool to Santa Claus with a matter-of-fact inquisitiveness that any scientist would recognize and respect.Maybe it’s this unconscious urge to protect children—and ourselves—that accounts for the popularity of the Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus editorial by newspaperman Frank Church. In 1897, after a girl wrote to his paper and begged to know whether Santa was real, Church famously replied that Santa existed “as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy.”

Who can object to that metaphorical delight? But Church then went on to seemingly diss science and reason. In this great universe, he wrote, the intelligence of humans approximated that of mere ants, incapable of grasping the unseen world: “Did you ever see fairies dancing on the lawn? Of course not, but that’s no proof that they are not there.” He wrote that without “childlike faith” in Santa Claus—and, I presume, another often-bearded supernatural being associated with this holiday—our existence would be intolerably dreary.

Personally, the only childlike faith that I value is children’s innate, irrepressible conviction in their own ability to puzzle things out. Remember, psychologists found that children felt pretty good after finally cracking the Santa case. The pursuit of rational understanding isn’t dreary; it’s beautiful and fun, suffused with creativity and hope. A child seeking the truth about Santa is much like a researcher investigating a massive black hole or unexpected chemical reaction or some alien creature that flickers with bioluminescence in the dark ocean depths.

I’ve seen photos of myself as a little girl perched on Santa’s knee, but I have no memories of how I perceived that experience. “When I was a kid, did you try to get me to believe in Santa?” I recently asked my parents. My father, a mathematician, scoffed. “Of course not,” he said. “We told you he was a mythological being that represented generosity and good cheer.”

Still, every December, my mother hung stockings above the chimney with care. And every Christmas Eve, she made sure cookies were left on a festively decorated plate, as though she truly believed St. Nick would soon be there.

These days, my daughter helps her set them out, along with a glass of chocolate milk. On Christmas morning, the cookies will be nibbled and the glass empty, and my children will gleefully open presents labeled: “From Santa.” Fully cognizant that Santa does not exist, they will exclaim “Wow, thanks, Santa!” and “Look what Santa gave me!” as my parents and I smile behind our cups of coffee, feigning surprise and interest in the gifts apparently delivered by that right jolly old elf.

The other day I asked my daughter, who is now ten, “Did you ever believe that Santa was real?”

“What are you talking about?” she said, deadpan, not even looking up from the book she was reading. “Of course Santa is real.”

__________________________________

Transient and Strange: Notes on the Science of Life by Nell Greenfieldboyce is available now via W. W. Norton & Company.