And yet again, we’ve reached the end of a long, bad list year.For the sake of posterity, and probably because we’re masochists, this week we’ve been counting down the 50 biggest literary stories of 2023, so you can remember the good, the bad, and all the literary cool girls we met along the way. But you’ve made it to the end, almost. So with no further ado, these are the biggest literary stories of the year that was:

10.

It was time for Colleen Hoover to face the backlash.

2022 was the year that Colleen Hoover—BookTok monarch and undisputed heavyweight champion of 2020s book sales—went stratospheric. She outsold John Grisham and James Patterson combined. She outsold Dr. Seuss. She outsold the damn Bible. As Alexandra Alter put it in a New York Times profile of the author, published in October of that year: “To say she’s currently the best-selling novelist in the United States, to even compare her to other successful authors who have landed several books on the best seller lists, fails to capture the size and loyalty of her audience.”

2023, however, saw the bloom go off the rose a wee bit.

It began in January, when Hoover announced that she and her publisher, Atria, were issuing a coloring book tie-in for her biggest hit, It Ends With Us. That decision was not well received. Here’s how Chels Upton, writing for Slate, described the backlash:

The negative response was swift and overwhelming, for obvious reasons. It Ends With Us is a book about domestic violence. Hoover detractors who say she romanticizes abuse had a new weapon in their arsenal: How can Hoover pretend she takes the subject matter seriously while creating cutesy, juvenile merchandise? Only 24 hours after the coloring book’s publication was announced, it was canceled due to pushback from both her fans and critics.

After this happened, there seemed to be something of a vibe shift within the CoHo fan community, and impassioned Hoover takedowns—often accusing the author of romanticizing abuse and glamorizing harmful relationships—began to garner hundreds of thousands of views on TikTok and YouTube.

Speaking to Jenna Hager Bush in June, Hoover seemed to take the criticism in her stride:

“If people don’t like what I write, I just try to avoid that side of it. I get it. It doesn’t bother me at all. I feel like when you have five books on the bestsellers list it’s very hard to be upset in any way by criticism. Because you know that people out there are enjoying your work, and I just keep my focus on that.”

Fair enough. –DS

9.

Elizabeth Gilbert pulled her Russia-set novel after social media blowback.

On June 6th, Elizabeth Gilbert announced on social media that her next novel, The Snow Forest, would be published by Riverhead in February 2024. The story was inspired by Karp Lykov and his family, members of an orthodox sect who fled to the Siberian forest to escape religious persecution from the Soviet government and lived there, cut off from human contact, for decades.

On June 12th, the Eat Pray Love author returned to social media to announce that she was indefinitely delaying publication due to a “enormous, massive outpouring of reactions and responses from [her] Ukrainian readers, expressing anger, sorrow, disappointment, and pain about the fact that [she] would choose to release a book in the world right now … that is set in Russia.” (The criticism largely manifested through one-star reviews on Goodreads, presumably before most reviewers had read the book.)

As you might remember, the internet exploded with think pieces and backlash to the backlash—some applauded Gilbert, many more expressed concern over censorship (self-imposed and otherwise), everyone continued hating Goodreads, and at least one person wondered if Gilbert was just bored. (As the New York Times pointed out, other novels set in Russia flew under the radar, perhaps indicating that popularity is not a writer’s best friend.) Riverhead, noticeably, stayed mum on the matter.

Will The Snow Forest ever see the light of day? Who knows. Decidedly not in February 2024, which will mark two years of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. –ES

8.

Private equity fund KKR bought Simon & Schuster.

No one was really expecting the Justice Department to halt Penguin Random House’s attempted purchase of its largest rival, Simon & Schuster, so when the final word came down in late 2022, it sent shockwaves through publishing (and through PRH). For many in the book world, the decision was a welcome one, a rare moment of government intervention on the side of the little guy (writers, in this case, and the potential size of their advances).

But as the dust settled we all began to wonder what would come next? Nick Fuller Googins wrote optimistically at Lit Hub about the huge positives of the employee ownership model, aka the Norton model:

The workforce of WW Norton has successfully owned and managed the venerable publishing house since shortly after World War II, when Mary Norton sold her stock to the company’s editors and managers. They drew up a Joint Stockholders Agreement that still remains in effect, allowing active Norton employees to elect leadership, participate in decisions affecting the company’s future, and share profits. Anyone who leaves Norton must sell back their shares, ensuring that no outside market exists for ownership of the company. There is no risk of a hostile takeover, no fear of an unexpected sale. The employees are free and independent to do what they have done so well for decades: publish kickass books.

Wow, yeah, that does sound really good… But it was not to be.

In early August of this year it was announced that KKR, a private equity fund, had purchased Simon & Schuster for $1.62 billion. It’s no secret that private equity funds like to acquire struggling companies, ramp up short term profits (often by slashing expenses), and then sell them for a profit; but as many have noted, Simon & Schuster is far from struggling. As Alex Kirshner’s great piece for Slate points out:

Simon & Schuster is already humming. It just reported a record sales year and seems to have been on the market in the first place mainly because its parent company, Paramount Global, saw it as “not core” and liked the chance to pay down some debt with the proceeds. A private equity firm’s specific designs for Simon & Schuster would be clearer if the book publisher were a disaster site, an iconic brand in need of better management so that it could return to its place as a literary pillar. But Simon & Schuster never lost that status in the first place, so KKR’s buyout lacks the patina of a rescue operation.

So will KKR leave well enough alone? The company has talked publicly about giving employees equity—which is a good sign—but ask anyone who’s worked in newspapers or magazines in the last 20 years about private equity and they’ll roll their eyes, or vomit, or both.

Check back in this space a year from now and we’ll have a better idea… –JD

7.

Ron DeSantis’s war on books continues unabated.

Soon-to-be failed presidential candidate and wearer of terrible boots Ron DeSantis has succeeded in making Florida one of the most hostile states in the union when it comes to books. Again and again DeSantis has doubled down on his role as Culture Warrior in Chief, ginning up conspiratorial fears of the Woke Mind Virus, mobilizing veritable armies of white suburban moms against queer people, Brown people, and the collected works of Kimberlé Crenshaw anything to do with Black history.

According to PEN America: “Florida is one of the worst states in the country for those who care about the freedom to read: 13 school districts in Florida banned books in the second half of 2022—more than in any other state—adding up to a total of 357 bans.”

And as our own Janet Manley asked back in May:

FLORIDA, ARE YOU OKAY?

I’ve kept a rough tally of things the sunshine state is afraid of:

the word “gay”

Oprah

reproductive rights

Mem Fox

drag shows

Judy Blume

fresh water

and things Florida thinks are fine:

assault weapons

alligators

parrot shirts and Crocs that come with a bottle opener

Are you a Floridian? How is the vibe down there right now? I’d love if you could let me know in the comments. <3

Perhaps the worst thing to come out of DeSantis’s unrelenting and deeply cynical fearmongering is that scourge of school boards everywhere, Moms For Liberty, cofounded by Tallahassee’s Jennifer Pippin and Sarasota’s Bridget Ziegler (she of the now infamous sex scandal). Though it appears the group is collapsing from within, much damage has already been done, as the Washington Post itemized this past May (translations mine):

“Nearly half of filings — 43 percent — targeted titles with LGBTQ characters or themes, while 36 percent targeted titles featuring characters of color or dealing with issues of race and racism.”

TRANSLATION: We don’t want to hear about you unless you’re white and straight.

“Many challengers wrote that reading books about LGBTQ people could cause children to alter their sexuality or gender.”

TRANSLATION: Books can turn you gay.

“Serial filers relied on a network of volunteers gathered together under the aegis of conservative parents’ groups such as Moms for Liberty.”

TRANSLATION: It only takes a few bad actors to corrupt an otherwise open society. This is the Tolerance Paradox at work.

“‘These censorship attacks on books have real-life human impacts that are going to resonate for generations,’ said John Chrastka, cofounder and executive director of library advocacy group EveryLibrary.”

TRANSLATION: The few hateful book-banners don’t actually care about the mental well-being of children.

“From the 2000s to the early 2010s, LGBTQ books were the targets of between less than 1 and 3 percent of book challenges filed in schools, according to ALA data. That number rose to 16 percent by 2018, 20 percent in 2020 and 45.5 percent in 2022, the most recent year for which data is available.”

TRANSLATION: This is a targeted, activist-driven culture war in the absence of any real policy ideas on the right.

“‘If that book was made without the strap-on dildo,’ Jennifer Pippin (founding chairman of Moms for Liberty) said, ‘that book wouldn’t be challenged.’”

TRANSLATION: Jennifer Pippin will not peg you, no matter how nicely you ask.

It’s hard to gauge whether we’ve reached peak book-banning, yet. My guess—as we enter an election year—is no. Thanks to DeSantis, politicians across the country have seen just how easy it is to mobilize vague conservative unease into full-blown, torch-bearing mobs. Whatever comes of the remainder of DeSantis’s ugly political career, his place in the annals of American demagoguery is assured, boots and all. –JD

6.

It was a big year for ghostwriters.

One of the biggest books this year—without a doubt—was Spare, which was published just as Harry and Meghan officially stepped down as senior royals. In the publishing industry, everyone was a bit stressed trying to get a copy of the book before the on-sale date (Alexandra Jacobs recounted the New York Times’ inability to get an advance copy, which meant she only had a day to read and review it.) We were teased audiobook clips of the now Duke of Sussex dealing with his frostbitten penis, but most importantly, we saw book sales soar: the day it went on sale, the book sold more than 1.4 million copies; in its first week it sold 3.2 million.

Then in May, “Harry’s ghostwriter” J.R. Moehringer broke the cardinal rule of celebrity ghostwriters (which many are contractually forbidden to speak about) and wrote a seven thousand word essay about what it was like to be the Royal’s ghostwriter (as well as Andre Agassi’s and Phil Knight’s). The essay is warm, informative, and telling: he describes an argument he had with Harry over how to end a “difficult passage”:

Some part of me was still able to step outside the situation and think, This is so weird. I’m shouting at Prince Harry. Then, as Harry started going back at me, as his cheeks flushed and his eyes narrowed, a more pressing thought occurred: Whoa, it could all end right here.

Of course Harry used a ghostwriter, but what does it mean when we begin to acknowledge that the books “by” our favorite celebrities are, in fact, written by writers like Moehringer, who also happens to have a Pulitzer and has written his own memoir and novel? Let’s call 2023 the year of the ghostwriter; with many high-profile (and high-advance) celebrity books published, it was inevitable that the details would be revealed—Britany Spears (who was reportedly paid a $12.5MM advance for her memoir) apparently had a team behind her that included the writer Sam Lansky; in Paris, Paris Hilton thanked her ghost writer, Joni Rodgers, as someone who “helped me find my voice.”

But it’s not just memoirs—celebrities who write fiction likewise use ghostwriters, as The Guardian explored over the summer. Teenage actress Millie Bobby Brown’s novel sparked some controversy when it was revealed that her fall novel was written with (or by?) a ghostwriter.

Their names might not be on the cover copy—yet. But perhaps we’ll see more acknowledgments in years to come #nametheghostwriter. –EF

5.

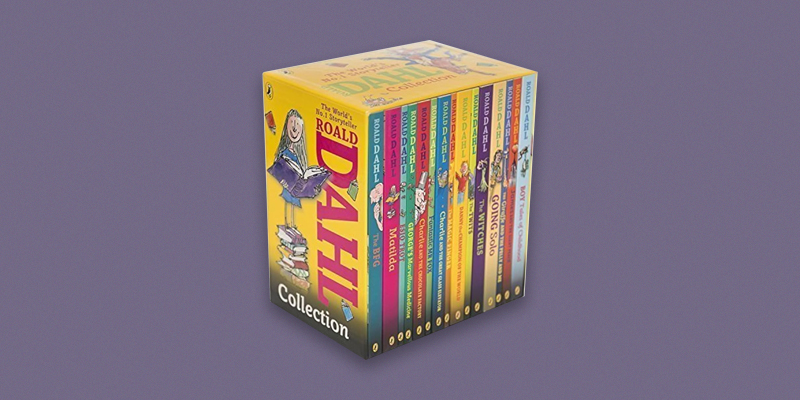

Posthumous editions of Roald Dahl’s books—and then Ian Fleming’s—ignited controversy.

In this time of deep partisan divisions, it was in a way refreshing to see people from across the political spectrum come together this year over one particular topic: outrage at Roald Dahl’s work being posthumously changed to reflect the suggestions of modern sensitivity readers.

It wasn’t just the usual right-wing bloviators getting up in arms about wokeness (although there was, of course, plenty of that)—Steven Spielberg and Salman Rushdie and Suzanne Nossel of PEN America and the Queen Consort all chimed in about it. In an unholy fusion worthy of David Cronenberg, knee-jerk defenders of the perceived right for a person to be as offensive as they’d like came together with champions of good writing and good humanity to decry Penguin’s decision to edit the texts. They swiftly changed course and brought out a batch of ‘classic’ editions of the Dahl books—indeed, so swiftly that one might believe it had been a double-dipping plan all along.

Stories followed about how Ian Fleming’s James Bond books were being edited for a reissue campaign, about how R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps books had been edited without his knowledge, and a new generation was introduced to the concept of bowdlerization.

And to be clear, some of the changes to the Dahl books in particular were unforgivable. Entire sentences added to the text, rhymes butchered, and a real “trees instead of forest” practice of removing specific words like ‘fat’ and ‘crazy’ or gender-specific pronouns while leaving the rest of the questionable context in place.

This is a complicated topic to discuss under the best of circumstances, and the internet of 2023 is certainly not the best of circumstances—but I’m going to give it my best shot. James Bond will always be a character defined by his casual racism and his brutality towards women, in service of the Crown. Roald Dahl was a terrible anti-semite and his books contain some of the nastiest sentences in fiction, children’s or otherwise. Agatha Christie really did title a book that, only to have it retitled twice. These things are true and it is in fact important that we know about them. Erasing any of this does nothing but try to sweep history under the rug, and anyone who has ever cleaned a house before knows that you can only get away with that for so long before all hell breaks loose.

It’s also true that it can hurt to read a slur, or a scene of sexual violence, or to in any way be thrown out of a work of fiction by a harsh reminder that the world used to be a crueler place. At a time when real violence is being done to marginalized populations, is it really such a big deal that we take steps to protect the more vulnerable among us?

But just as conflict is not abuse and retweets are not endorsements, assuming that all readers who encounter these texts in their unexpurgated form will take them at face value is a colossal misunderstanding. We read in order to make sense of the world, and while it might be true that Roald Dahl had plenty of shitty stances on beauty, race, size, and intelligence, he also wrote with grace about the incredible powers of imagination and love. When we read Ian Fleming and see James Bond talking casually about rape or racism, it is valuable to be able to say “you know, I don’t agree” instead of just pretending that it wasn’t there at all. After all, a version of King Lear with a happy ending isn’t a good revision; it’s one that misses the entire point of the story. –DB

4.

Writers and other literary people won some key battles against corporate interests.

Though we didn’t need any further evidence that solidarity is always a good look, unions racked up some significant wins in 2023. In February, after almost hitting the 100-day mark on the picket line, HarperCollins Union members (UAW 2110) agreed to a tentative deal with management. In April, the Writers Guild of America went on strike for 148 days. Writing about authors on the picket line, Alexis Gunderson made the point that “when there are already so few paths to having a stable career as a writer, the prospect of losing this one has also proved to be galvanizing.”

Of course, not everyone was galvanized—Drew Barrymore was set to host the 2023 National Book Awards, until she announced that her eponymous show would resume production amid the strike—without its writers.

“The National Book Awards is an evening dedicated to celebrating the power of literature, and the incomparable contributions of writers to our culture,” the National Book Foundation said in a statement. “In light of the announcement that The Drew Barrymore Show will resume production, the National Book Foundation has rescinded Ms. Barrymore’s invitation to host the 74th National Book Awards Ceremony. Our commitment is to ensure that the focus of the Awards remains on celebrating writers and books, and we are grateful to Ms. Barrymore and her team for understanding in this situation.”

LeVar Burton, who walked the picket line as a SAG member during this year’s 118-day actors’ strike, replaced her as host. Let this be a lesson to all of us! –JG

3.

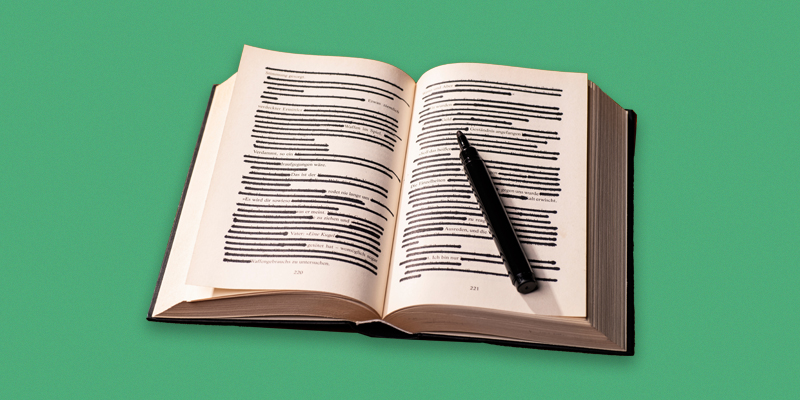

The book banning continued.

The biggest literary story of 2022 was the national proliferation of book bans. Unfortunately, the trend did not abate in 2023—though neither did the efforts to push back.

PEN America recorded 3,362 cases of book bans in the 2022-’23 school year, a 33% increase from the 2,532 bans in the 2021-’22 school year. Over 40 percent of these bans are happening in Florida. The most banned books include Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower, John Green’s Looking for Alaska, and of course, Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer: A Memoir.

The American Library Association has also recorded a record high of book bans and attempted book bans in 2023; this year was notable for the fact that the challenges had notably expanded from school libraries to public libraries. “The irony is that you had some censors who said that those who didn’t want books pulled from schools could just go to the public libraries,”’Deborah Caldwell-Stone, who directs the association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, told the AP. Super.

“I never thought I’d be a president who is fighting against elected officials trying to ban and banning books,” said President Biden in April, at a White House event honoring teachers. “Empty shelves don’t help kids learn very much. And I’ve never met a parent who wants a politician dictating what their kid can learn, and what they can think, or who they can be.” In June, the Biden administration promised to appoint an “anti-book ban coordinator” in the Education Department; that person was finally named in September, though the scope of their powers is fairly limited.

In October, Scholastic came under fire for a policy change around its beloved Scholastic Book Fairs: some books had been separated into a separate, optional collection, which they titled Share Every Story, Celebrate Every Voice. This collection included “most of the books dealing with issues of race, gender and sexuality,” according to NPR. The internet was displeased.

Initially, Scholastic defended their decision, explaining in a press release:

There is now enacted or pending legislation in more than 30 U.S. states prohibiting certain kinds of books from being in schools—mostly LGBTQIA+ titles and books that engage with the presence of racism in our country. Because Scholastic Book Fairs are invited into schools, where books can be purchased by kids on their own, these laws create an almost impossible dilemma: back away from these titles or risk making teachers, librarians, and volunteers vulnerable to being fired, sued, or prosecuted.

But after a few days of public pressure, Scholastic president Ellie Berger apologized and reversed the decision. “This fall, we made changes in our U.S. elementary school fairs out of concern for our Book Fair hosts,” Scholastic told USA Today in a statement. “In doing this, we offered a collection of books to supplement the diverse collection of titles already available at the Scholastic Book Fair. We understand now that the separate nature of the collection has caused confusion and feelings of exclusion. We are working across Scholastic to find a better way.”

And there has been other pushback as well: In May, PEN America, along with Penguin Random House and a group of authors, parents, and students, filed a “first of its kind” federal lawsuit to prevent the removal of books from school libraries in Escambia County, Florida. In June 2023, Governor Pritzker signed a bill making Illinois the first state to outlaw book bans; in September, California’s Governor Newsom followed suit. Elsewhere, individual parents and educators continue to fight the good fight. After all: the vast majority of Americans do not want this. Which is, I suppose, a certain kind of silver lining. –ET

2.

Writers are killed in Gaza; censored, silenced, and standing in solidarity in the U.S.

For over two months now, Israel (with the full military, financial, and diplomatic support of the US) has laid siege to the already-benighted Gaza strip, killing at least 18,272 people (including 8,000+ children), injuring at least 49,229, displacing at least 1.8 million, and damaging or destroying at least 305,000 homes. Despite calls for a permanent humanitarian ceasefire from the UN, the Pope, every major human rights association the world over, and tens of millions of protestors, this horror, this genocide, continues apace.

Gaza’s literary and journalistic communities have suffered heavy losses.

At least 75 Palestinian journalists and writers, as well as numerous members of their immediate and extended families, have been killed by Israeli airstrikes and sniper fire since the war on Gaza began. On October 20, the novelist, poet, and educator Heba Abu Nada was killed, along with her son, in their home in south Gaza. On November 19, Belal Jadallah, the “godfather of Palestinian journalism,” was killed while trying to reach his family. On December 7, the poet and scholar Refaat Alareer was killed in an Israeli airstrike that also killed his brother, his sister, and four of her children.

The damage to Gaza’s cultural sector has been so devastating, and so clearly targeted, that many are now referring to it as a “cultural genocide.”

Here in the US, many literary and cultural institutions showed that the McCarthyist streak in American public life is alive and well.

Artforum‘s editor-in-chief was fired for publishing a letter expressing solidarity with Palestinians. Several events for A Day in the Life of Abed Salama author Nathan Thrall were called off. Salvadoran poet and activist Javier Zamora was disinvited from a panel for publicly supporting Palestinian liberation. eLife editor-in-chief Michael Eisen, was fired for reposting an article from The Onion. 92NY canceled an event featuring the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen after he signed an open letter critical of Israel. Zibby Owens withdrew sponsorship from the National Book Awards, citing its “pro-Palestinian agenda.”

However, we also saw many inspiring displays of Palestinian solidarity to counteract this chilling of free speech.

Thousands of writers signed an open letter expressing solidarity with the people of Palestine. More than a dozen of this year’s National Book Award finalists took to the stage to call for a ceasefire. Over 2000 poets and writers pledged to boycott the Poetry Foundation, citing “a recent instance of prejudiced silencing.” Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Anne Boyer resigned from the New York Times with this extraordinary letter. The Giller Prize ceremony in Toronto was interrupted by pro-Palestinian protesters, who were later supported by more than 1,700 Canadian writers. The kidnapping of poet Mosab Abu Toha by Israeli forces prompted an outcry from the literary community (Abu Toha was later released and eventually made it to Egypt with his wife and children). Hundreds of literary translators signed a statement in solidarity with Gaza, as did dozens of indie bookstores and hundreds of small publishers from around the world. And Rupi Kaur publicly declined an invitation from the White House.

As human rights activist and Booker Prize-winner Arundhati Roy said in a powerful address to the Munich Literature Festival back in mid-November:

If we allow this brazen slaughter to continue, even as it is livestreamed into the most private recesses of our personal lives, we are complicit in it. Something in our moral selves will be altered forever.

…

The world must intervene. The occupation must end. Palestinians must have a viable homeland.

If not, then the moral architecture of western liberalism will cease to exist. It was always hypocritical, we know. But even that provided some sort of shelter. That shelter is disappearing before our eyes.

So please—for the sake of Palestine and Israel, for the sake of the living and in the name of the dead, for the sake of the hostages being held by Hamas and the Palestinians in Israel’s prisons—for the sake of all of humanity—cease fire now. –DS

1.

The rise of OpenAI, ChatGPT, and fears of an AI takeover.

The jury is still out on whether or not artificial intelligence will replace the novelist as we know it or is, in fact, one big dumb bubble. The one thing we know for certain is that everyone has an opinion about AI and will freely share it. Here at Lit Hub, we’ve published more than our fair share this year, pro and con:

Randy Sparkman wondered if a computer could write like Eudora Welty:

This time, I asked the model to take on the role of tutor. Teach me more about Eudora Welty’s writing. Give examples of her use of language. Ask me questions that develop my understanding of her writing and use of language, until I say “class is over.”

Debbie Urbanski actually thinks novelists should embrace artificial intelligence:

I worry that we’re forgetting how amazing this all is. Rather than feeling cursed or worried, I feel lucky to get to be here and witness such a change to how we think, live, read, understand, and create. Yes, we have some things to figure out, issues of training, rights, and contracts—and, on a larger level, safety—but I think it’s equally important to look up from such concerns from time to time with interest and even optimism, and wonder how this new advance in technology might widen our perspectives, our sense of self, our creativity, and our definition of what is human.

Naomi S. Baron feels strongly that we need to defend human writing in the age of AI:

If writing helps us think, what happens when we surrender the process to AI? We risk becoming cognitively and expressively disempowered. […] If we cede to AI final say about words and even commas, we jeopardize more than artistic pride. We risk convincing ourselves that in the name of efficiency, it’s harmless for AI to assume ever wider swaths of what we previously would have written ourselves.

Gabrielle Bellot takes a more nuanced approach and approaches the problem from the opposite direction, through literature:

Artificial intelligence has its precursors in many of our earliest achievements as a species. It’s in our tools, or technology—not just the obvious cases, like chatbots, but in the simpler ways that we have been taught to make technologies extensions of our own flesh-and-blood bodies.

This isn’t a bad thing, in and of itself. It’s how we’ve survived this long as a species, using our tools to do things that other creatures can do—flight, deep dives into the ocean’s blues, enhancing our strength and environmental resistance and speed through weapons and clothes and vehicles. Technology is the story of humanity from our earliest days in firelit caverns, which is why Freud famously called humans “prosthetic gods” in Civilization and Its Discontents.

I have no doubt that we will publish many more such pieces in 2024, of differing positions, about AI and its relationship to writing.

And while I think people are right to worry that a lot of writing jobs will be made redundant by AI, it’s worth pointing out that the vast majority of those jobs are predicated on a terrible version of the Internet that relies on an endless churn of content, with little to no value. (I’d also point out that human beings write thousands of terrible novels a year, too, but that might get me in trouble.)

To be frank, AI is not only the biggest news story of the year, it’s going to be the biggest story of our era, whether we like it or not. –JD