Fierce, Fearless and Fun: How Maggie Higgins Broke New Ground For Women in Journalism

Jennet Conant on the Adventures of One of America's First Female Foreign Correspondents

“In the early sixties in the Washington bureau of the Times, the period around 9:00 pm used to be known as the Maggie Higgins Hour… Her frequently exclusive stories obviously had to be checked out, and the Maggie Higgins Hour arrived when the bureau phone would start ringing with calls from New York on the latest Higgins headlines, just out in the Herald Trib. Could the bureau match?”

–Tom Wicker, On Press

*

On December 12, 1960, a banner headline on the front page of the Herald Tribune announced Maggie Higgins’s latest exclusive: “Kennedy Sr. Tells of His Family.” Much to the consternation of her competitors, the ubiquitous Higgins had somehow managed to establish herself as an insider in the new Kennedy administration, and she had been rewarded with a long, intimate interview with the controversial patriarch of the president-elect’s sprawling Irish Catholic family. The subhead of her story read, “He Urged His Son to Run for President? Nonsense.”

Her exclusive was picked up by the Washington Star, and the AP, and was quoted in the daily papers and the nightly news broadcasts. When calls poured in from reporters at other publications wanting to know how Higgins scored her sit-down with Joe Kennedy just one month after his son’s election, she sounded smug, explaining that she had pitched the story while at the family’s Hyannis Port compound along with a handful of other correspondents “personally known to the president.” Tidbits from the interview continued to circulate for days afterward, including the tycoon’s insistence that there was “absolutely no truth” to rumors that he planned to be the power behind the throne, and was hunting for a house in Washington and would soon be taking up residence near 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

A week earlier, when Jack Kennedy ignited a firestorm by nominating his brother for attorney general, Maggie devoted an entire column to pushing Bobby for the post. In “His Brother’s Keeper,” she reported that the thirty-five-year-old Democratic campaign manager, who had contributed greatly to JFK’s victory, was sensitive to the charges of nepotism, but the president-elect would not be deterred from giving him the job, and they hoped the public would come to see it as a well-deserved reward. Before the column came out, she sent Bobby a draft, along with a note that conveys how involved she had become in helping to advance his political fortunes:

Bobby:

I left many details about you out because your situation is so uncertain even though the observations your father made about you are my sentiments exactly. But just wait. One day I’m going to blow the myth about the “ruthless” Bobby Kennedy so high it will never be put back together again. I hope this article is satisfactory. I tried to lay to rest the old bogey about your father manipulating the white house and it was easy to do because any first-hand observer can see this is utterly contrary to the truth.

I’ll call or perhaps you could call me at North 7 7070.

All the best,

Maggie

Bobby sent a handwritten reply: “Your article was certainly most kind—and most appreciated.” He added that he and Ethel were “looking forward to seeing you next Saturday,” a reference to baby Linda Hall’s christening day. At the church, the new priest who had taken over the parish declined to let Ruth Montgomery serve as godmother. Bobby and Ethel Kennedy offered to stand in, and they became Linda’s official godparents.

By the time the new administration was being sworn in, Maggie was at the forefront of Washington social life. When the Women’s National Press Club gave a reception for the new members of the president’s cabinet on January 21, 1961, she introduced the new attorney general, who, in typical Kennedy fashion, was half an hour late for the party in his honor. Waving away his apologies, Maggie took the breathless Ethel by the arm and steered the couple into the ballroom, presiding over a private party for all the guests who stayed.

Maggie continued to help burnish the Kennedy image. She penned a glowing profile of the family matriarch, Rose Kennedy, for McCall’s. The magazine was so pleased it put Maggie on a $1,000 monthly retainer. She followed up with another puff piece. Packed with admiring quotes from Kennedy cronies, “The Private World of Robert and Ethel Kennedy” underscored her own position as a trusted friend and member of the clan.

She and Peter Lisagor teamed up to write a flattering profile of Tish Baldrige, who had been appointed Jackie Kennedy’s social secretary, and another gauzy feature about the Kennedys’ new style of entertaining, “RSVP—The White House,” detailing the scandalous changes the young, modern president and his wife were introducing to the “forbidding, museum-like atmosphere of the White House,” including a switch from the torturous white tie and tails to black tie at formal affairs, and abandoning the traditional receiving line.

Maggie’s enviable access was observed up close by Jim O’Donnell, who left journalism to join the Kennedy administration in 1960. “Jack always cultivated newspapermen, he brain-picked, which I think a good politician should do,” he said, noting that Kennedy had a dozen or so favorites among the press corps, including Higgins, Lisagor, Lippmann, Cronkite, and Elie Abel of the Times. The president valued Maggie for her candor—she could be counted on to tell it like it was, with no sugarcoating. “Kennedy would call her, much more often than he called me. He was much closer to her. She was a power in the press those days.”

Once, after she had written a piece that angered Kennedy, he expressed his disappointment in her. As she related the conversation to O’Donnell later in the day, the president had complained, “Marguerite, I thought you were a friend of mine. You could at least have called me up. You’re going out with this thing. It’s critical. You could have called me up.”

“But Jack, it was eleven in the evening,” she had protested, trying to explain that she was on deadline and unable to put in a call to his secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, at such a late hour.

“Look, I don’t care what time of day or night,” Kennedy had said. “If you’re going to be on the front page of the Herald Tribune with something that concerns my government, you can roll me out at three in the morning. I’ll only be angry if you didn’t check it. Because (a) you got it wrong, and (b) I could have given you some added information.”

O’Donnell marveled at Maggie’s relationship with the president, whom she called “Jack,” something he could never bring himself to do. “She had a really fine relationship with President Kennedy,” he said, adding unprompted that their after-hours contact was strictly “platonic.” For a reporter to be given the president’s private number was incredible, he added; “she could literally call him at midnight and get through.”

The lure of the Kennedys was irresistible, and not just for Maggie. Many journalists shared her exhilaration at the arrival of the New Frontiersmen, who seemed so bright, energetic, and full of ideas. “Few presidents ever had a more adoring press corps,” observed Lippmann biographer Ronald Steel, who detailed the conversion of the Trib’s influential political columnist into “one of the shining ornaments of the Kennedy administration.”

Even in this period of adulation, friendly columnists and correspondents did not suspend all critical judgment. Ben Bradlee, who went on to become a legendary editor of the Washington Post, wrote about the excitement and fascination of unexpectedly having a friend elected president, but he noted, “For a newspaperman it is all that, plus confusing: are you a friend, or are you a reporter? You have to redefine ‘friend’ and redefine ‘reporter’ over and over again, before reaching any kind of comfort level.” There is a line reporters know they should not cross. It is a boundary that denotes separate and distinct professional agendas, distance, and if not impartiality then at least some semblance of neutrality. During the first weeks after Kennedy was elected, Bradlee admitted that he often found it difficult to toe that line, and it took time before he “got it right.”

Maggie waltzed across the line without missing a beat. There is no sign she experienced so much as a twinge of ethical queasiness about her overfamiliarity with the first family. The more time she spent as a special columnist, the less attention she paid to the ordinary rules of journalism. Confident she could negotiate what Bradlee called the “complicated perimeters of friendship,” and the conflict between the private and public spheres, she ignored all the textbook warnings about compromising relationships.

As she morphed from foreign correspondent to Cold War pundit and anticommunist crusader, she became increasingly partisan. She saw herself as an advocate, identifying areas of instability, advancing her interpretation of events, and recommending courses of action. Promoting the Kennedys—their policies, their appointees, their cult of personality—was all of a piece with her worldview; she was their emissary, and they were part of her larger cause. The martial sentiment of the president’s inaugural address was music to her ears, and she liked his public pronouncements on combating communism. Even though they sometimes differed on issues, there was a shared sense that this was their generation’s turn to lead, and the beginning of a new period of global commitment.

Maggie and the Kennedys were made for each other. The brothers shared her insatiable appetite for news and political gossip, and they enjoyed the lively give-and-take of journalistic shoptalk, the no-holds-barred, who’s-in-who’s-out roundup of state officials, politicians, reporters, friends, enemies, and acquaintances. For her, the Kennedys were the holy grail of sources—the highest of high-placed authorities—providing unparalleled access, allowing her to be first with the news and the most complete with the background and context of events. Her files during this period are crammed full of correspondence with Bobby, including notes, telegrams, call slips, meeting dates, and dinner plans. She was a regular recipient of RFK’s leaks, and reciprocated with stories he found useful.

For her, the Kennedys were the holy grail of sources—the highest of high-placed authorities—providing unparalleled access.She also wrote regularly to Jack, her easy rapport with him evident in the telegram she sent after he clinched the nomination at the Los Angeles convention on July 15, 1960:

CONGRATULATIONS ON NOMINATION, LAST NIGHT’S SPEECH, AND, IN FACT, ON PRACTICALLY EVERYTHING STOP HOPE YOU WILL TIDY UP SUCH MATTERS AS THE CONGO, CUBA, ETC, SO I CAN ATTEND NEXT CONVENTION STOP WISH I’D BEEN THERE.

Kennedy wrote back a week later, noting that the “chaotic last hours” at the Biltmore had prevented him from responding that night. “I, of course, regret that you were left behind on the war fronts of the Congo and Cuba,” he added. “I shall, however, do my best to provide a breathing spell in the summer of 1964.”

Maggie had missed the convention because she was stuck in Washington writing a series of articles about the Congo, and the future of the new African states, sixteen independent nations that had just been admitted to the United Nations. In one of her better recent scoops, “Summer Scandal,” she reported that the NATO base in Greece was being used as a stopover for Russia’s Ilyushin planes, which were being sent “to win friends and influence the Congolese on communism’s behalf.”

In March of 1961, when trouble erupted in the Belgian Congo Republic, Maggie jumped on a plane to cover the hostilities. The page-one headline was classic Higgins: “Congolese Hostile to U.N., but Welcome an American.” The American was Maggie, of course. Her story opened in familiar dramatic style with her arrival in Leopoldville:

As we stepped out of the tiny blue and white Cub plane that had flown us across the river at Brazzaville, a helmeted Congolese soldier, complete with paratroop boots and grenades on his belt, waved a burp gun somewhat indecisively in our direction.

“Go back,” he said. “We don’t want any more United Nations people here.”

“Pay no attention,” said an Air France hostess, who was armed with only a pert blue uniform and an air of supreme confidence.

Readers who plowed on would learn that Congolese president Joseph Kasavubu’s government had tried to topple the communist-backed rebel leader Antoine Gizenga by cutting off supplies to his regime in Stanleyville. European civilians were fleeing across the border and the province was beset by violence. Maggie scored a world beat by being the first reporter to send word from Leopoldville of the arrival of Indian combat troops. She did it by locating the only open wireless circuit in the republic, and punching out her own story on the teletype machine in the communications center. A week later, she pinned down Gizenga for an hour-long talk in his house in Stanleyville. The interview made even bigger news: he told her that unless the Western powers officially recognized him by April 15, he would expel British, French, and U.S. consuls from his city. More headlines followed, and more Higgins fanfare.

Newsweek reported that in the space of two weeks, Maggie, showing a touch of her old “fire-horse flamboyance,” had filed two world exclusives to the Herald Tribune. Making her entrance in a posy-printed dress in place of her usual fatigues, and gobbling anti-dysentery pills, Higgins had apparently refused to take no for an answer when the media-shy Gizenga turned down her interview request. The fact that no Trib correspondent had been in Stanleyville since 1877, when the famed reporter and explorer Henry Morton Stanley visited the spot after tracking down the long-lost Dr. David Livingstone, made her scoop all the more newsworthy.

“Is it courage, initiative, or sheer blind luck that gives Marguerite Higgins her exclusive stories from the Congo?” Newsweek asked rhetorically. “Her envious male colleagues, who have been there for months, have good reason to debate this stickler.”

Not wanting to lose her momentum, Maggie planned to fly to Vienna to cover Kennedy’s first meeting with Khrushchev, a superpower conference to be held in June. When Donovan told her he was sending their White House correspondent, David Wise, Maggie was livid. Ignoring his objections, she took leave and paid her own way, later claiming it was for a freelance piece.

Donovan’s patience had been tried past endurance. He told the higher-ups he was tired of being saddled with the “care and feeding” of Higgins. She answered to no one. Every assignment became a test of wills. She was obstinate, obsessive, and impossible to control. Maggie, in turn, complained of being “frozen out” and threatened to resign. Tittle-tattle about the bureau squabbling made the columns and added to her growing reputation as a diva. But the bottom line was that her name was an asset to the paper. Donovan had little choice but to put up with her.

On the second day of the Vienna summit, Kennedy and Khrushchev got around to the subject of Berlin and the ongoing debate over reunification. Khrushchev, who had little respect for the inexperienced young president, demanded a peace treaty and recognition for East Germany. Berlin needed to become a strictly neutral city, and the Western powers would have access to the city only with East German permission. Kennedy was amazed. He maintained the Western powers had every right to be in Berlin, having defeated Germany in the Second World War. He declared that the national security of the U.S. was directly linked to that of Berlin. Khrushchev exploded, banging his fist on the table, and said, “I want peace, but if you want war that is your problem.” The meeting ended ominously, with the Soviet leader insisting his decision to sign a peace treaty with East Germany in six months was irrevocable. The president responded, “If that’s true, it’s going to be a cold winter.”

__________________________________

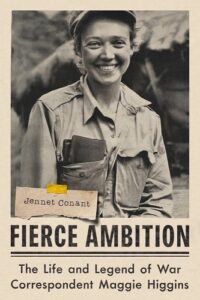

Excerpted from Fierce Ambition: The Life and Legend of War Correspondent Maggie Higgins by Jennet Conant. Copyright © 2023. Available from W.W. Norton & Company.