Everything You Need to Know About Groundbreaking Queer Feminist Science Fiction Writer Joanna Russ

Jon Michaud Talks to Nicole Rudick About "One of the Fiercest Critics Ever to Write About Science Fiction"

When she was in high school in the early 1950’s, Joanna Russ (1930–2011) read Mark Twain’s short story “A Medieval Romance,” about a duke without a male heir who brings his daughter up to fill the role, hiding her gender from all. Things get complicated when the duke’s niece falls in love with his “son,” threatening to reveal her true identity and upset the succession. Russ, who would go on to become a groundbreaking queer feminist science fiction author, recalled that Twain’s story became “an extremely important part of my fantasy life.” In college, however, Russ struggled to reconcile that fantasy life with the heteronormative expectations around her. Those feelings “didn’t count, except in my own inner world in which I could not only love women but also fly, ride the lightning, be Alexander the Great, live forever, etc.” Eventually Russ would find a way to channel that disjunction into a remarkable body of literature, including the revolutionary novel The Female Man (1975).

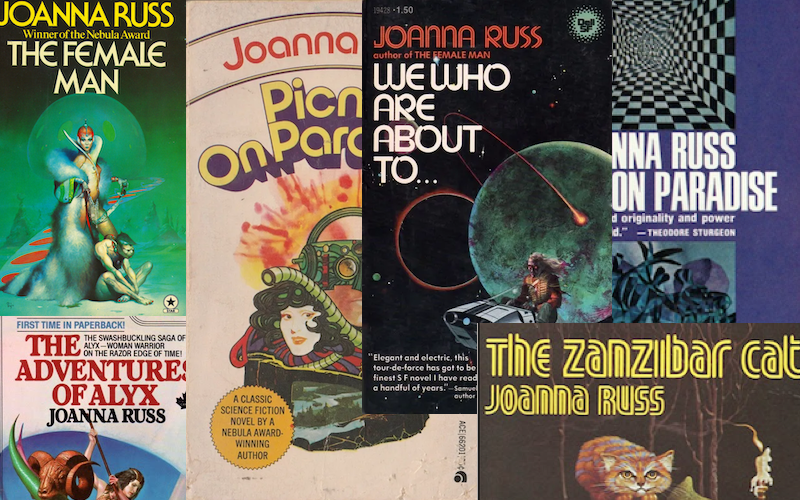

That novel and a selection of other novels and stories by Russ have now been collected and reissued by the Library of America. Not long ago, I sat down with the volume’s editor, Nicole Rudick, to talk about Russ’s life, work, and her reputation as one of the fiercest critics ever to write about science fiction.

*

Jon Michaud: How did you discover Russ’s work and what were your first impressions?

Nicole Rudick: The first thing I read of hers was The Female Man. My husband was reading a ton of science fiction and when he finished the novel he said, “You should read this.” It was incredible to me that this book existed and I had never heard of it. I couldn’t believe that it wasn’t more widely known, because it’s just astonishing, in subject and style, and it still feels so urgent, even though it was written fifty years ago. It’s not a utopia, but when Russ writes about women’s freedom on the women-only Whileaway, I was nearly in tears. After that, we tracked down all of her books, which were a little hard to find, because they’re all out of print.

JM: How did this anthology come about? Why did you think this was a good time to relaunch Russ to the world?

NR: It seemed obvious to me that her work should be back in print. The Library of America had done a number of Ursula K. Le Guin and Philip K. Dick anthologies. They had also published Octavia Butler’s work and had done the first volume of The Future is Female. So they had a recent history of publishing the work of science fiction writers. It seemed obvious that Russ should be among them. She’s essential to the history of the genre, and I wanted to see her alongside those writers. I pitched it to the LoA, and they said yes, pretty much immediately.

I was eager to see it published in-series, in one of those beautiful black covers, because her work deserves to sit alongside Le Guin, Dick, and Butler in a place of importance. And not just among the science fiction writers but in relation to significant literary writers in general. So then it became a matter of making a volume that could be priced in such a way that people who didn’t know her would feel comfortable picking it up. Too many pages and the volume becomes more expensive. Once we had a page range, it became a matter of selecting work that would put her best foot forward—which novels and stories best exemplified her talents and the variety of work she had written.

I knew we had to put all of the Alyx stories in, which had never all been collected before. [Samuel R.] “Chip” Delany is Russ’s biggest fan and was her longtime friend—they met in 1966. I got to tell him that I was doing this Russ volume, and he was over the moon. He insisted that we put in “A Game of Vlet,” which had never been published with the other Alyx stories, so now we have her early fantasy stories, starring Alyx, all in one place. The Female Man had to be in there and We Who Are About To…, a novel I really love, because it starts off like a typical science fiction story—a crash landing on a desolate planet—but turns into a completely different kind of book in the second half, a story about a solitary woman who is coming to terms with her past, her present, and her future and her place in society. Then On Strike Against God, which is a realist novel about a woman realizing she’s a lesbian. It’s taken very much from Russ’s own life. The two other stories are “When it Changed,” which was her breakthrough short story, just before The Female Man, and “Souls,” a gorgeous story about an abbey invaded by Norsemen. There’s a bit of a surprise at the end, which I won’t spoil.

This volume doesn’t represent her voluminous nonfiction feminist writing and criticism. She also wrote a children’s book, Kittattiny, which l read to my daughter and we both love.

JM: Let’s talk about Russ’s development as a writer. She grew up in New York, went to Cornell. She studied with Nabokov, correct?

NR: True, though I think it’s a little overstated. She studied with him in her last year at Cornell and dedicated “Picnic on Paradise” to him and to S.J. Perelman, but I think she came to feel a little silly about that. She named them both as stylistic influences, and she and Nabokov certainly share a metafictional approach, but she talked a lot more throughout her life about George Bernard Shaw.

She grew up loving science, and was a top 10 finalist in the Westinghouse Science Talent Search in 1953. She graduated high school early, and then went to Cornell and switched over to literature. She said that she came out to herself as a lesbian privately when she was a kid and went right back in because she had no models. She didn’t feel that it was real, that it could be done. And that continued at Cornell, where things were pretty traditional in terms of gender roles. And then she went to Yale and studied playwriting but found that she was not very good at it. When she returned to New York, she worked odd jobs, did some theater work, and made some adaptations for radio at WBAI. She was also writing stories and publishing them in little journals and SF magazines.

In the late 60s, she started writing stories about Alyx. She said it was the hardest thing she ever did in her life, to conceive of a tough, independent female protagonist and get it on the page. Feminism was not widespread in the United States at that moment and Russ wasn’t involved in consciousness-raising groups or anything like that, so it was a solitary time to be writing these sorts of things. But they did well. Picnic in Paradise, her novella about Alyx, won a Nebula Award. And then in ‘67, she was back at Cornell, as a teacher, and in ‘69, there was a colloquium on women in the United States organized by the university in the intercession period—Betty Friedan and Kate Millett and a bunch of other panelists talking about sexuality, race, and why women see each other the way that they do. They approached these issues as social problems, not individual problems. Russ was there, and her description of it is so funny—“Marriages broke up; people screamed at each other who had been friends for years…. The skies flew open.” A wave of feminism washed over Cornell, and she sat down and wrote “When it Changed” in the weeks afterwards. Six months later, she saw a novel in the story and wrote The Female Man. But she couldn’t find a publisher. She wanted it published by a trade press and they all rejected it. The excuses were like, “There’s more feminism than science fiction”—that from Viking Press. A lot of women editors were baffled by it and turned it down. It finally got bought by Frederick Pohl [at Bantam Books] in 1975.

JM: What was the reception for The Female Man when it was published?

NR: A lot of people loved it. Over ten years, it ended up selling 500,000 copies. But plenty of others took issue with it. They thought it was angry, too political, that there was too much message. There were also complaints about the way it was written, that it was too hard to follow. There hadn’t been anything like it before in science fiction, and the novel is quite pointed in its feminism and critique of social systems. Some people were not ready for it. I imagine that even now there are people who will think it’s too much. Russ is so no-nonsense, so unabashed about writing how and what she wants to write. I’m trying to avoid using words like “aggressive” and “angry”—she was aggressive and angry and she had every reason to be angry, but these are terms that she gets saddled with, without also acknowledging that she was acid and brilliant and funny and playful.

JM: How were Russ’s relations with her peers—the New Wave writers of the 1960s who were showcased in Harlan Ellison’s Again, Dangerous Visions anthology?

NR: The key American figures of that group are Russ, Delany, Le Guin, James Tiptree, Tom Disch, and Dick, though they weren’t all doing the same sort of things. She and Disch were friendly, but she and Dick didn’t always see eye to eye. Russ met Delany very early and they remained friends for the rest of her life. He admired her writing from the start and published her in Quark, the anthology he edited with Marilyn Hacker. Delany and Russ were correspondents for decades, and their letters to one another are prolific and deeply intellectual and opinionated. They write at length about science, literature, life and what they are thinking, doing, and reading. Sometimes Russ will take him to task for what she sees as mistakes, and Delany is very forgiving of her when she is angry with him—more so than anybody else.

JM: Delany, too, was an outsider from the mainstream of science fiction. He was black and gay. That must have helped them to establish a bond.

NR: They were the intellectuals. And she was so insistent about her opinions and, later, about her needs as a disabled person that I think she felt herself a bit on the outside. She was a woman writing science fiction, a feminist, a disabled person, and a lesbian. She wrote work that didn’t always fit easily into one genre or another, and she introduced feminist criticism to SF. All of this puts her in a pretty unique position. She was also tough on people and demanding, so perhaps not always very likable.

JM: Russ was critical of Le Guin, wasn’t she?

NR: Russ’s issue with Le Guin, put simply, is that Le Guin was one of the best known women writing science fiction and she was not dealing with feminism or the subject of women in a way that Russ felt she should be. Russ felt that Le Guin had an obligation, as a prominent woman of science fiction, to address these issues. Le Guin has written herself that she was late to do so. The best known point of contact for their disagreement is Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, where she used male pronouns to refer to androgynous characters, and Russ called her out publicly.

Russ would write bitterly about Le Guin in her private letters. But it’s important to recognize that they were coming at science fiction from very different backgrounds and with very different aims. There are people who prefer one over the other, but you can love both quite easily. And I do. There are fundamental differences in what they were after. It’s a gross simplification, but Le Guin is sociological, and Russ is political. Russ believed that there was no separation between politics and life and that invented worlds should not be escapes from reality. But there are moments in her letters where she admits that she admires things about Le Guin—she once called it “disappointed adoration.” When Russ’s physical problems made it impossible for her to keep writing, she wrote to a friend that she was envious of Le Guin because she was still writing away. It’s a much more complex relationship than I think is understood.

JM: We’ve talked about Le Guin, and we’ve talked about Delany. Another important figure is James Tiptree, who also had a long correspondence with Russ. Did Russ know that Tiptree was actually a woman?

NR: No. Nobody did. Tiptree wrote a beautiful letter to Russ, revealing herself to be Alice Sheldon—I remember Julie Phillips reproducing part of it in her biography of Tiptree. She wrote to apologize for the deception, and she feared that she was going to lose all of her friends. Russ didn’t care about the Tiptree business, which is lovely. They stayed correspondents for years, and Tiptree was admiring of Russ’s anger but also felt burned by it. Tiptree was writing to Le Guin at the same time, and they complained to each other about that aspect of Russ sometimes. I think Tiptree was a bit closer with Le Guin than with Russ, and you can see Tiptree in the middle when Russ complains to her about Le Guin. And Russ was a sort of intermediary between Tiptree and Delany.

JM: Talk a little bit more about Russ as a critic. Why is she so important and what’s her legacy as a critic?

NR: As I said, she introduced feminist critique to science fiction. It provided a new way to look at what was happening in SF stories—not only to assess contemporary work but to think about the history of the genre, what had been written, what had gotten published, how it was read and received. And that was essential because the way women were portrayed in literature, and by extension the way they were treated in life, had to change. She called people out quite boldly. Her later book How to Suppress Women’s Writing is a damning collection of the various ways women and their writing have been dismissed over time. That book, too, was rejected numerous times, also by women. One editor said she heard “this particular whine” often. But Russ was very vocal about the idea that if you can’t imagine in science fiction a world where women are equal, then how can you do it in real life? She also critiqued writing for its stylistic and conceptual flaws. Her critical writing is of a piece with her fiction in that she didn’t mince words. She could be really brutal in her criticism. But I think by calling people out she made people aware of their attitudes and biases.

JM: Is there an example of a book or a writer that she called out?

NR: “Robert Silverberg is a sossidge-factory trying to become an artist.” That’s one she ended up apologizing for much later, and it’s pretty extreme. A lot of people took issue with her reviews, but she wasn’t often wrong.

JM: You’ve already talked a little bit about Russ’s queer identity and that she struggled with it. She was actually married for a while, yes?

NR: A very short marriage. She got married because that’s what people did.

JM: She was struggling against expectations as a person and she was also struggling against expectations as a science fiction writer, right? She has a lot of genre elements in her work, but she deploys them in unconventional ways. Was there a kind of liberation on the page where she could do whatever she wanted, a liberation that she perhaps didn’t find in her life?

NR: Yes, there was liberation, and she was also thinking on the page. There’s so much thinking in We Who Are About To… and The Female Man. Both deal, in different ways, with open-ended questions: What is the best way to live? How do we reconcile our needs and selves with a society that refuses to fully recognize us? She didn’t have the answers herself. Even after she was known to be a lesbian, she could still be cagey about it. Her sexuality was complicated. She did have mostly relationships with women, but occasionally there was a man.

JM: Who, among today’s writers, would you say is indebted to Russ’s work?

NR: That’s a good question and hard to answer because Russ has been under the radar for so long. I think she has been an influence on Carmen Maria Machado, Nisi Shawl, and Stephanie Burt, and during her own lifetime, she had fans in Dorothy Allison, Adrienne Rich, Joan Acocella, and Dale Spender. I should mention, too, that she taught writing and literature at the university level for decades and lectured at the Clarion Writers’ Workshop. I don’t think we have a sense of how influential she may have been.

JM: Is it true that Russ was also a practitioner of fanfiction?

NR: Oh yes. “Kirk/Spock” slash fic. In the early 80s, a friend of hers passed along some K/S someone else had written, and Russ was immediately into it. K/S was mostly written by women, and it told stories about romantic and/or sexual relationships between Kirk and Spock. It was appealing both as a vision of a romantic relationship between equals and as pornography for women. Russ loved it and started writing it and published a handful of stories in zines. It’s kind of amazing—she gets the characters right, despite the change in situation. And it makes sense within her larger body of work. She wanted to see what it would look like and know how it would feel to experience a caring and equal sexual relationship.

JM: What resources are available for readers who want to learn more about Russ’s life?

NR: There isn’t much. Gwyneth Jones wrote a critical work called Joanna Russ about Russ’s writing that incorporates some of her biography. And Farah Mendelsohn has edited On Joanna Russ, a collection of essays in which different writers address various aspects of her career and writing. I think there’s some research going on in France right now on Russ, but there is as yet no major biography. But I can’t imagine a better subject.

*

Nicole Rudick is the author of What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle (Siglio, 2022). Her criticism has been published most recently in The New York Review of Books, The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Apollo, and she has been an editor at The Paris Review, Bookforum, and Artforum.